|

The Spoils was first published in 1951; its three parts present:

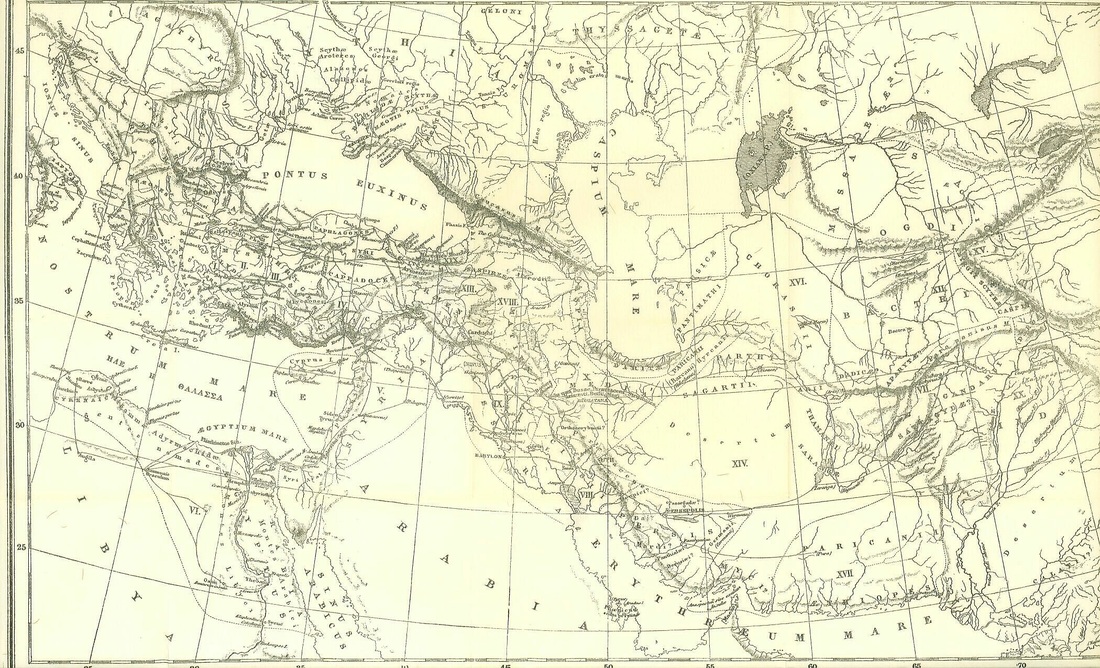

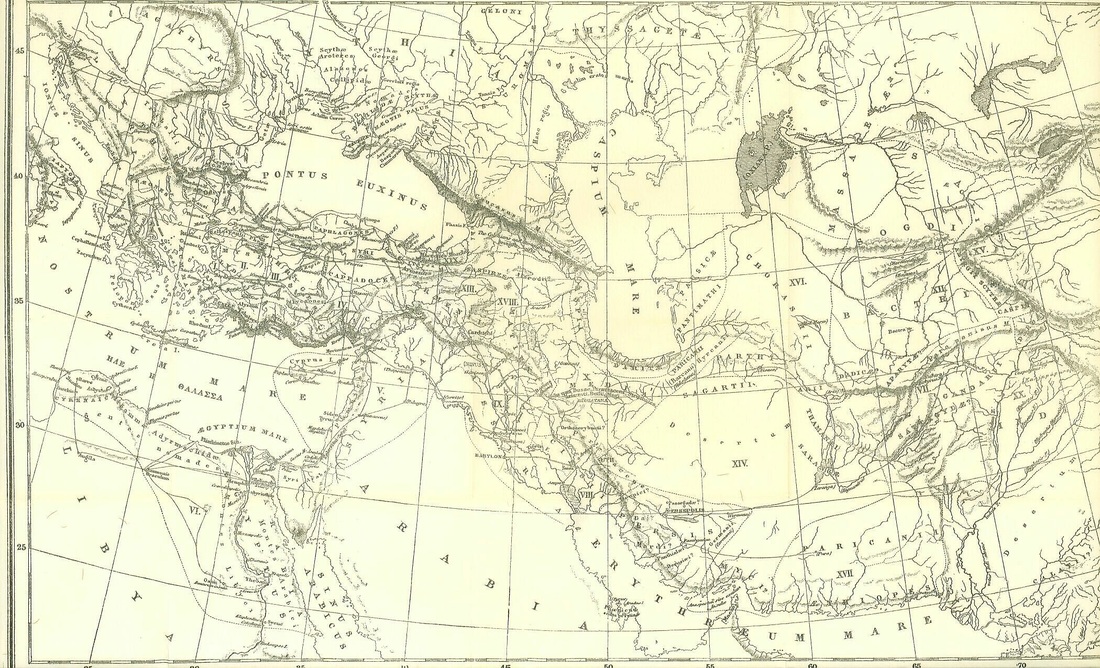

(1) the region popularly called the “mid-east” (2) Persia (3) Bunting’s second world war. Webwise, annotation is simpler than once upon a time but challenges remain in the variety of transliteration. Unless otherwise noted, reference the Columbia Encyclopædia (Third Edition). The title refers to a line from the Qor’an sura viii: “the spoils are for God.” [Bunting’s note; Complete Poems, Oxford 1994] The sons of Shem are the legendary founders of the tribes of the Semitic people: Asshur (Israel); Lud (Lydians); Arpachshad (Chaldea); Aram (roughly Syria). About 30 years before the poem was written, another English Orientalist who also served in the RAF, T.E. Lawrence, detected a decline in “orthodox Islam” in favour of nationalism; Bunting underscores the “family resemblances” by turning to the origins of a long troubled region. Bunting: “I always looked upon the Bible as prison reading.” |

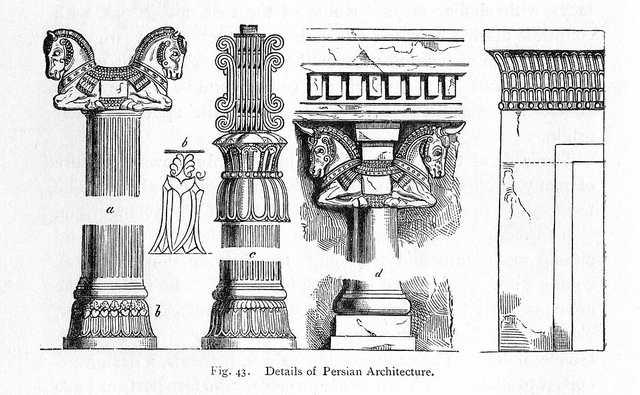

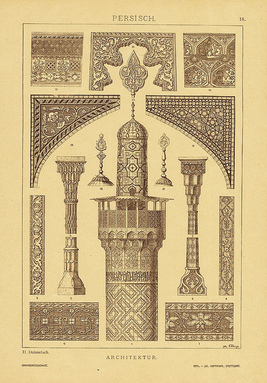

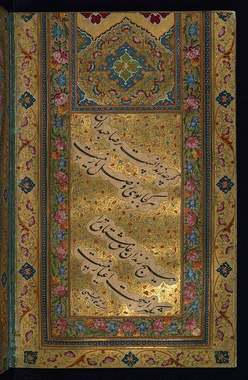

The second movement of the poem presents a rapid run-through of Persian history; ideally, it will prompt independent research, and perhaps a visit to any museum that can boast a Persian Gallery. The name Khayyam should be familiar to any reader of poetry; that he is described as a “better reckoner” refers to his reformation of the calendar at the request of the Seljuk emperor, Malekshah (or Malik Shah). The decline of the Seljuk rule is presented by three items of “public spirit.” Bunting then leaps to the Iran he knows: Mosavvor (painter), Naystani

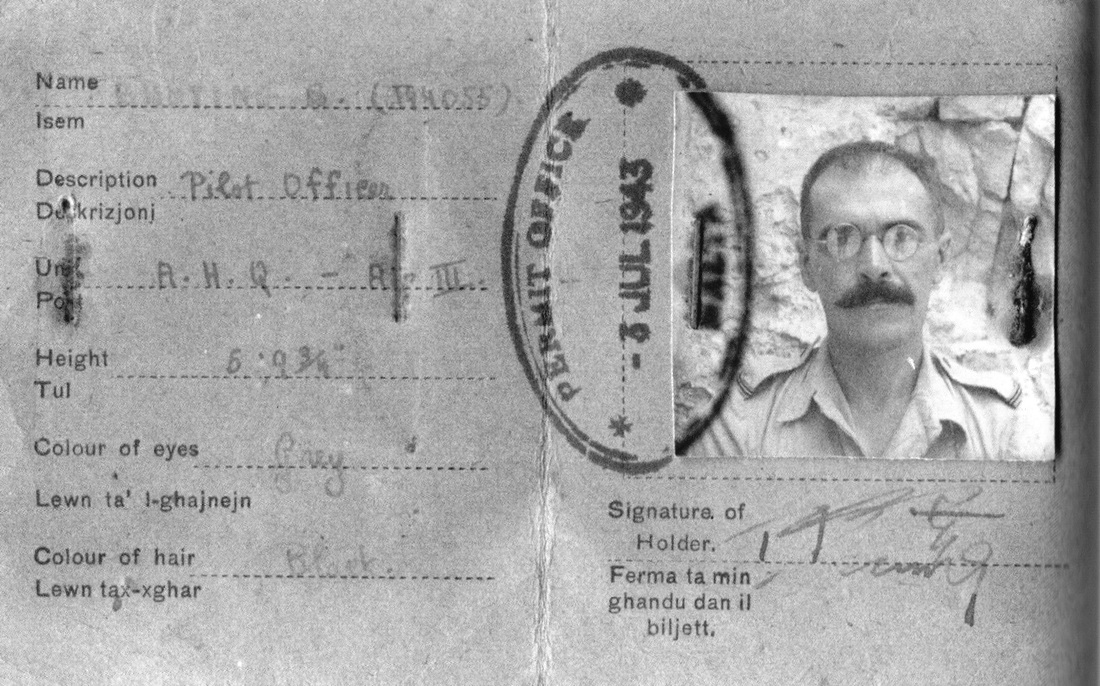

(flautist), Taj and Moluk-e-Zarrabi (singers) were his contemporaries (as indicated by the phrase “dawn-cold radio”). “Vafur” refers to all the tools related to opium. (Bunting was often offered opium, vodka and tea while performing his duties with the British Embassy; at least once his host inquired if he (Bunting) preferred boys or girls.) The third movement includes something of the war as experienced by Bunting, over forty when he entered the RAF: “old in that war. . .” There is something “broken” about this movement, reflecting a world that will not be repaired by war. “One cribbed in a madhouse” is surely a reference to Ezra Pound, confined to St Elizabeth’s in Washington D.C. since 1948; if the other poets remain obscure, the general sense is clear enough. Bunting once declared that T. S. Eliot would ultimately be judged a “minor poet.” He always held an unshakeable contempt for Auden. Flight Lieutenant Idema, the American who wouldn’t fight for Roosevelt, but donned a British uniform to fight “for Churchill” was described by Bunting as “one of the bravest men I ever met.” Bunting quotations from A Strong Song Tows Us: a life of Basil Bunting; Richard Burton, Prospecta Press 2013. For now, this is the biography of Basil Bunting, though I think it might be improved by a detailed chronology. |

|

Biographical Note

At the close of 1918, Basil Bunting was released from prison where he had served six months as a conscientious objector under conditions disturbingly similar those experienced by François Villon nearly 500 years before. Over the next twenty years, Bunting would write some poems, work odd jobs, and travel (he would get as far west as Los Angeles). In 1930, while staying with Ezra Pound at Rapallo, Bunting came across a French prose translation of the Persian epic, the Shahnameh. The book lacked a cover and a title page, and the concluding chapters were gone, but it was compelling reading, and when Bunting got as far as he could with it, there seemed little else to do but learn Persian so he could find out how it ended. So was Basil Bunting introduced to Persian literature, central to “The Spoils” and root cause to an astonishing chapter of his career. By 1939, Bunting was back in England, still scrounging for work, and watching preparations for war. He hoped to find a place in the Navy, but failed the medical exam. As war gathered force on the continent, he approached the RAF and, after convincing a doctor to let him memorize the eye chart, entered the air force in spring, 1940. Aircraftman Second Class Basil Bunting reported for duty in the north of England in September 1940, assigned to the Balloon Command, a strategic line of defence against the Luftwaffe. In December he was assigned to Rosyth, Scotland, and his quarters were aboard a converted millionaire’s yacht, The Golden Hind.

|

It was a period, as often in war, of wearisome waiting. Bunting’s natural restlessness, coupled with a desire for a promotion (and the accompanying salary hike) filed a form highlighting his linguistic skills and mentioning his knowledge of Persian literature. In the spring of 1942, the order came down: he would be reassigned to Persia, as an interpreter. Bunting’s journey to the East was no quick flight: a troop ship left Glasgow in May, arriving at South Africa by mid-June. There, the troops rested for a month, before continuing the journey, now aboard a United States vessel, across the Indian Ocean to Karachi. (A Yankee error, perhaps: they were supposed to go to Bombay.) At last, in September, Bunting set foot in Iran, his long imagined Persia. There were three phases to his long stay in Persia: first, as an interpreter and intelligence operative for the British Army, then a position as part of the British Embassy, and finally as special correspondent for The Times. Bunting was not cut out for the idle duties of a bureaucrat: he became one of the few Westerners who knew something about the region. He gained fluency in local dialects, and his characteristic curiosity, free from any racist snobbery, made him welcomed as an intelligent individual rather than despised as British intelligence operative. |

|

THE SPOILS

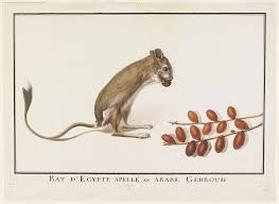

These are the sons of Shem, after their families, after their tongues, in their lands, after their nations. Man’s life so little worth, do we fear to take or lose it? No ill companion on a journey, Death lays his purse on the table and opens the wine. ASSHUR: As I sat at my counting frame to assess the people, from a farmer a tithe, a merchant a fifth of his gain, marking the register, listening to their lies, a bushel of dried apricots, marking the register, three rolls of Egyptian cloth, astute in their avarice; with Abdoel squatting before piled pence, counting and calling the sum, ringing and weighing coin, casting one out, four or five of a score, calling the deficit; one stood in the door scorning our occupation, silent: so in his greaves I saw in polished bronze a man like me reckoning pence, never having tasted bread where there is ice in his flask, storks’ stilts cleaving sun-disk, sun like driven sand. Camels raise their necks from the ground, cooks scour kettles, soldiers oil their arms, snow lights up high over the north, yellow spreads in the desert, driving blue westward among banks, surrounding patches of blue, advancing in enemy land. Kettles flash, bread is eaten, scarabs are scurrying rolling dung. Thirty gorged vultures on an ass’s carcass jostle, stumble, flop aside, drunk with flesh, too heavy to fly, wings deep with inner gloss. Lean watches, then debauch: after long alert, stupidity: waking, soar. If here you find me intrusive and dangerous, seven years was I bonded for Leah, seven toiled for Rachel: now in a brothel outside under the wall have paused to bait on my journey. Another shall pay the bill if I can evade it. LUD: When Tigris floods snakes swarm in the city, coral, jade, jet, between jet and jade, yellow, enamelled toys. Toads crouch on doorsteps. Jerboas weary, unwary, may be taught to feed from a fingertip. Dead camels, dead Kurds, unmanageable rafts of logs

hinder the ferryman, a pull and a grunt, a stiff tow upshore against the current. Naked boys among water-buffaloes, daughters without smile treading clothes by the verge, harsh smouldering dung: a woman taking bread from her oven spreads dates, an onion, cheese. Silence under the high sun. When the ewes go out along the towpath striped with palm-trunk shadows a herdsman pipes, a girl shrills under her load of greens. There is no clamour in our market, no eagerness for gain; even whores surly, God frugal, keeping tale of prayers. ARPACHSHAD: Bound to beasts’ udders, rags no dishonour, not by much intercourse ennobled, multitude of books, bought deference: meagre flesh tingling to a mouthful of water, apt to no servitude, commerce, or special dexterity, at night after prayers recite the sacred enscrolled poems, beating with a leaping measure like blood in a new wound: These were the embers . . . Halt, both, lament . . . : moon-silver on sand-pale gold, plash against parched Arabia. What’s to dismay us? ARAM: By the dategroves of Babylon there we sat down and sulked while they were seeking to hire us to a repugnant trade. Are there no plows in Judah, seed or a sickle, no ewe to the pail, press to the vineyard? Sickly our Hebrew voices far from the Hebrew hills! ASSHUR: We bear witness against the merchants of Babylon that they have planted ink and reaped figures. LUD: Against the princes of Babylon, that they have tithed of the best leaving sterile ram, weakly hogg to the flock. ARPACHSHAD: Fullers, tailors, hairdressers, jewellers, perfumers. ARAM: David dancing before the Ark, they toss him pennies. A farthing a note for songs as of the thrush. ASSHUR: Golden skin scoured in sandblast a vulture’s wing. ‘Soldier, O soldier! Hard muscles, nipples like spikes. Undo the neck-string, let my blue-gown fall.’ Very much like going to bed with a bronze. The child cradled beside her sister silent and brown. Thighs in a sunshaft, uncontrollable smile, she tossed the pence in a brothel under the wall. LUD: My bride is borne behind the pipers, kettles and featherbed, on her forehead jet, jade, coral under the veil; to bring ewes to the pail, bread from the oven. Breasts scarcely hump her smock, thighs meagre, eyes alert without smile mock the beribboned dancing boys. ARPACHSAD: Drunk with her flesh when, polished leather, still as moon she fades into the sand, spurts a flame in the abandoned embers, gold on silver. Warmth of absent thighs dies on the loins: she who has yet no breasts and no patience to await tomorrow. |

ARAM:

Chattering in the vineyard, breasts swelled, halt and beweep captives, sickly, closing repugnant thighs. Who lent her warmth to dying David, let her seed sleep on the Hebrew hills, wake under Zion. What’s begotten on a journey but souvenirs? Life we give and take, pence in a market, without noting beggar, dealer, changer; pence we drop in the sawdust with spilt wine. II

They filled the eyes of the vaulting with alabaster panes, each pencil of arches spouting from a short pier, and whitewashed the whole, using a thread of blue to restore lines nowhere broken, for they considered capital and base irrelevant. The light is sufficient to perceive the motions of prayer and the place cool. Tiles for domes and aivans they baked in a corner, older, where Avicenna may have worshipped. The south dome, Nezam-ol-Molk’s, grows without violence from the walls of a square chamber. Taj-ol-Molk set a less perfect dome over a forest of pillars. At Veramin Malekshah cut his pride in plaster which hardens by age, the same who found Khayyam a better reckoner than the Author of the Qor’an. Their passion’s body was bricks and its soul algebra. Poetry they remembered too much, too well. ‘Lately a professor in this university’ said Khayyam of a recalcitrant ass, ‘therefore would not enter, dare not face me.’ But their determination to banish fools foundered ultimately in the installation of absolute idiots. Fear of being imputed naïve impeded thought. Eddies both ways in time: the builders of La Giralda repeated heavily, languidly, some of their patterns in brick. I wonder what Khayyam thought of all the construction and organization afoot, foreigners, resolute Seljuks, not so bloodthirsty as some benefactors of mankind; recalling perhaps Abu Ali’s horror of munificent patrons; books unheard of or lost elsewhere in the library of Bokhara, and four hours writing a day before the duties of prime minister. For all that, the Seljuks avoided Roman exaggeration and the leaden mind of Egypt and withered precariously on the bough with patience and public spirit. O public spirit! Prayers to band cities and brigade men lest there be more wills than one: but God is the dividing sword. A hard pyramid or lasting law against fear of death and murder more durable than mortar. Domination and engineers to fudge a motive you can lay your hands on lest a girl choose or refuse waywardly. From Hajji Mosavvor’s trembling wrist grace of tree and beast shines on ivory in eloquent line. Flute, shade dimples under chenars breath of Naystani chases and traces as a pair of gods might dodge and tag between stars. Taj is to sing, Taj, when tar and drum come to their silence, slow, clear, rich, as though he had cadence and phrase from Hafez. Nothing that was is, but Moluk-e-Zarrabi draws her voice from a well deeper than history. Shir-e Khoda’s note on a dawn-cold radio forestalls, outlasts the beat. Friday, Sobhi’s tales keeping boys from their meat. A fowler spreading his net over the barley, calls, calls on a rubber reed. Grain nods in reply. Poppies blue upon white wake to the sun’s frown. Scut of gazelle dances and bounces out of the afternoon. Owl and wolf to the night. On a terrace over a pool vafur, vodka, tea, resonant verse spilled from Onsori, Sa’di, till the girls’ mutter is lost in whisper of stream and leaf, a final nightingale under a fading sky azan on their quiet. They despise police work, are not masters of filing: always a task for foreigners to make them unhappy, unproductive and rich. Have you seen a falcon stoop accurate, unforeseen and absolute, between wind-ripples over harvest? Dread of what’s to be, is and has been-- were we not better dead? His wings churn air to flight. Feathers alight with sun, he rises where dazzle rebuts our stare, wonder our fright. |

III

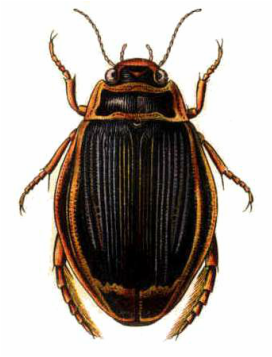

All things only of earth and water, to sit in the sun’s warmth breathing clear air. A fancy took me to dig, plant, prune, graft; milk, skim, churn; flay and tan. A side of salt beef for a knife chased and inscribed. A cask of pressed grapes for a seine-net. For peace until harvest a jig and a hymn. How shall wheat sprout through a shingle of Lydian pebbles that turn the harrow’s points? Quarry and build, Solomon, a bank for Lydian pebbles: tribute of Lydian pebbles levy and lay aside, that twist underfoot and blunt the plowshare, countless, useless, hampering pebbles that spawn. Shot silk and damask white spray spread from artesian gush of our past. Let no one drink unchlorinated living water but taxed tap, sterile, or seek his contraband mouthful in bog, under thicket, by crag, a trickle, or from embroidered pools with newts and dytiscus beetles. One cribbed in a madhouse

set about with diagnoses; one unvisited; one uninvited; one visited and invited too much; one impotent, suffocated by adulation; one unfed; flares on a foundering barque, stars spattering still sea under iceblink. Tinker tapping perched on a slagheap and the man who can mend a magneto. Flight-lieutenant Idema, half course run that started from Grand Rapids, Michigan, wouldn’t fight for Roosevelt, ‘that bastard Roosevelt’, pale at Malta’s ruins, enduring a jeep guarded like a tyrant. In British uniform and pay for fun of fighting and pride, for Churchill on foot alone, clowning with a cigar, was lost in best blues and his third plane that day. Broken booty but usable along the littoral, frittering into the south. We marvelled, careful of craters and minefields, noting a new-painted recognisance on a fragment of fuselage, sand drifting into dumps, a tank’s turret twisted skyward, here and there a lorry unharmed out of fuel or the crew scattered; leaguered in lines numbered for enemy units, gulped beer of their brewing, mocked them marching unguarded to our rear; discerned nothing indigenous, never a dwelling, but on the shore sponges stranded and beyond the reef unstayed masts staggering in the swell, till we reached readymade villages clamped on cornland, empty, Arabs feeding vines to goats; at last orchards aligned, girls hawked by their mothers from tent to tent, Tripoli dark under a cone of tracers. Old in that war after raising many crosses rapped on a tomb at Leptis; no one opened. Blind Bashshar bin Burd saw, doubted, glanced back, guessed whence, speculated whither. Panegyrists, blinder and deaf, prophets, exegesists, counsellors of patience lie in wait for blood, every man with a net. Condole with me with abundance of secret pleasure. What we think in private will be said in public before the last gallon’s teemed into an unintelligible sea-- old men who toil in the bilge to open a link, bruised by the fling of the ship and sodden sleep at the handpump. Staithes, filthy harbour water, a drowned Finn, a drowned Chinee; hard-lying money wrung from protesting paymasters. Rosyth guns sang. Sang tide through cable for Glasgow burning: ‘Bright west, pale east, catfish on the sprool.’ Sun leaped up and passed, bolted towards green creek of quiet Chesapeake, bight of a warp no strong tide strains. Yet as tea’s drawing, breeze backing and freshening, who’d rather make fast Fortune with a slippery hitch? Tide sang. Guns sang: ‘Vigilant, pull off fluffed woollens, strip to buff and beyond.’ In watch below meditative heard elsewhere surf shout, pound shores seldom silent from which heart naked swam out to the dear unintelligible ocean. From Largo Law look down, moon and dry weather, look down on convoy marshalled, filing between mines. Cold northern clear sea-gardens between Lofoten and Spitzbergen, as good a grave as any, earth or water. What else do we live for and take part, we who would share the spoils? 1951 |

|

BUNTING'S VILLON

Basil Bunting's Villon (1925) is not a translation nor a dramatic monologue, but a modernist poem tackling a favourite medieval theme: mortality, particularly in the context of the ancient formula: "Life's short, Art's long." A very real and busy criminal career led to Villon's banishment from Paris in 1463; his prison experience, without doubt, greatly shortened his life. But though most of the facts we have about Villon have been gathered from the police blotter of his time, he also had a contemporary reputation as a poet. Bunting served six months in prison at the close of the Great War as a conscientious objector, where he suffered conditions frighteningly similar to those of Villon ("Whereinall we differ not."); his poetic reputation would not be secured until he was in his mid-sixties. Since his death in 1985, Bunting has come to be regarded as one of the major poets of the XX century. |

|