|

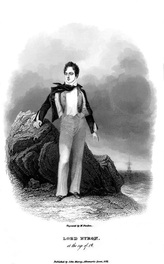

There’s the memorable moment in Joyce’s PORTRAIT when young Stephen first suffers for the sake of his art, defending the poetic reputation of Lord Byron. Judging from the rather slippery chronology of the novel, I would guess that this takes place when Stephen is twelve or thirteen years old. If it seems remarkable that a bunch of boys would discuss the merits of poetry, no less precocious is Stephen’s choice of Cardinal Newman as best English prose stylist (personally, I did not begin to hold style as a particular virtue until I was much older – maybe fifteen or sixteen). There are those who say Stephen’s elevation of Newman is but unconscious toadying to Jesuit authority; others note it as foreshadowing his susceptibility to the religious rhetoric of the coming sermons. If valuing “prose style” reflects matured judgement, I can see Stephen’s picking up this praise for Newman from one of the faculty; more interesting is the contest between Byron and Tennyson, neither of whom I fancy were assigned reading at Clongowes. It is amusing that Stephen calls Tennyson “only a rhymester” when early in Don Juan Byron rhymes “Intellectual” with “hen pecked you all” but I doubt Stephen had yet come across Don Juan. I think Stephen had read Byron, because I believe there’d have been a volume of Byron among the small collection of Books (those yet to be pawned) owned by Stephen’s father, Simon – right next to the lyrics of Thomas Moore. As for Tennyson, Stephen will call him Alfred Lawn Tennyson in Ulysses – implying continuing disdain for his aristocratic retreat from the sordid grit of daily living. Turn from Tennyson to Whitman, and it is hard to believe that they were contemporaries. (But, to be fair to Alfred, he contributed generously to a fund for Whitman’s security.)

Byron has long been the delight of biografiends; his life was filled with incident and variety and, I suppose, scandal. If it’s biography you’re looking for, there’s the Leslie Marchand: three volumes and splendidly authoritative. Biography is sometimes used as a well-honed axe; fortunately, Byron was not one inclined to let others speak on his behalf, and perhaps the most pleasant way to engage with Byron is through his voluminous letters and journals. Turning to the year 1817, among the first letters of the year was written to his good friend, Thomas Moore.

Byron had left England the year before, after the dissolution of his marriage, and at this point in his correspondence he will still write of his pending return. By January 1817, Byron had set up house in Venice, and there commenced his thirtieth year; the letters present a considerably energetic force, at turns a travelogue, or meditative essay, or literary criticism and ruminations on the art of poetry, next anecdote and gossip and politics, and then sometimes sheer bagatelle. Throughout the letters runs the steady refrain of postal problems: misdeliveries, lost items, return to sender addressee unknown. Byron wrote his publisher, John Murray, several times NOT to send to the Venetian Foreign Office, asking “Why do you send anything to such a ‘den of thieves’ as that?” Murray persisted. “Where do you suppose the books you sent me are?” writes Byron. “At Turin! This comes of ‘the foreign office’ which is foreign enough, God knows, for any good it can be of to me, or any one else, and be damned to it, to its last Clerk and first Charlatan, Castlereagh.” Castlereagh was a special enemy of Byron’s, and his name may be familiar to the long memories of my Irish listeners. But on the whole, I think we find more expressions of gratitude that the system worked at all. Almost 200 years after Byron was writing, there’s talk that the world’s postal systems verge upon extinction; if you credit that, then prepare to lose an astonishing example of human cooperation. In any event, it should not be a luxury to have the time to consider what you mean to say. It is within recent memory that you would place a long distance call, then wait until the operator would ring you with an open line; now people sport telephonic earpieces never to be out of touch. The illusion of the importance of immediacy has somewhat spoiled the art of correspondence.

|

Byron died in 1824, seeking Grecian liberties, and it is touching to come across plans for his future, just as it is grim to encounter reminders of the dangers of the early XIX century, in particular the widespread diseases of the age (barely noticeable in the novels of the time except for dramatic purposes). As news of Byron’s death spread, rumours regarding the “real story” fanned the funeral pyre: let me say clearly that the cause of death was not an especially virulent strain of syphilis, but Mediterranean tick-fever, which Byron probably contracted from his habit of letting his dogs sleep on his bed. (’Twould be a subject fit for Marianne Moore: Byron’s menagerie, which around this time included 10 horses, 8 enormous dogs, 3 monkeys, 5 cats, 5 peacocks, 1 eagle, 1 crow, 1 falcon, 2 guinea hens, and 1 Egyptian crane. While attending Cambridge, Byron was greatly upset by the regulations against keeping a dog; so he kept a bear.) As winter neared its end, Byron fell ill, and wrote to Thomas Moore:

“I have been very ill with a slow fever, which at last took to flying, and became as quick as need be. But, at length, after a week of half-delirium, burning skin, thirst, hot headache, horrible pulsation, and no sleep, by the blessing of barley water, and refusing to see any physician, I recovered.” It is difficult to determine to which Byron gave greatest credit for his restored health: the barley beverage, or refusing to see a doctor. The seemingly boundless energy of Byron would occasionally flare up as invective: fundamentally comic, and cosmopolitan. Worried that his publisher Murray might be tampering with his texts, Byron wrote: “If he has, by the Ass of Balaam! he shall endure my indignation.” Speaking of a doctor, Byron complains about “that despicable lisping old ox and charlatan … of all the perambulating humbuggerers, that aged nondescript is the principal.” When I come across a phrase as lively as “perambulating humbuggerer,” I just can’t wait to use it! Another example of a finely worded curse: “may it please the beneficent Giver of all Good to damn [her] in the next world!” While it is misleading to employ XX terms for XIX events, it is still useful to point to Byron as a best-selling author, and as a poet who had extraordinary popular appeal. I think we might be able to trace, through the course of the XIX, a shift in poetry’s place in the popular imagination: more and more, poetry addressed fewer and fewer. There are, of course, notable exceptions: Browning was popular enough that his poems were printed on the backside of train schedules (something to do while waiting for the train, I suppose) but Browning was also known and perhaps even valued for his difficulties and challenges. Even though Byron provided annotations for his poems, they were not to elucidate arcane intellectual conceits, but sought to clarify references outside the common English reader’s experience: Byron may have been high-born, but he was not especially high-brow, and it is a statement of high praise when I call him one of the world’s most entertaining poets. The poems on which his initial reputation were based, the brooding romantic tales like Childe Harold, caught the public’s imagination at a time when it seemed the solidity of Europe (then a zillion nation states undergoing the terrorism of Bonaparte) was about to dissolve forever: these poems still work their magic upon readers willing to give themselves over to the pleasure of the text. Byron’s lyrics, are yet another case of Byron’s uncanny ability to write for anyone who reads: and they rapidly transcend speculative thoughts regarding Byron’s secret autobiography to become part of the reader’s autobiography. Of DON JUAN, I can only say that over the past century, it has risen considerably in critical and academic favour, and certainly places Byron among the great satirists we have mentioned over the past several weeks: Swift, Wyndham Lewis, Orwell, and at least one facet of Henry David Thoreau. Simply defined, a lyric is a short poem meant first and foremost to be heard, to be sung, to be unleashed into the air. I now will offer four lyric poems, one by Thomas Moore, whom I mentioned earlier, two by Byron, our birthday boy, and finally a short sweet lyric by Yeats, which will be our fulfilment of the urgent task to present words by Yeats as often as possible. Moore and Yeats were both Dubliners, but Byron’s background is a bit more complicated since he was, as it were, a Scottish Lord, but Byron always had mixed feelings about that. Writing to Sir Walter Scott, Byron expressed fond memories of Scotland, but on other occasions, to different correspondents, he denied any and all scottisms. However, I must declare that I believe his Scots background key to the pleasure his lyrics (or these two) afford me: I don’t want to analyze the thing to death, but the rougher sound of english spoke by scots, the droning rhythm of the pipes, even the cold and damp of a January morning in Scotland, all these inform Byron’s poems in a way which is hard to prove, but which contribute mysteriously to the sound or aura of Byron’s best. But let’s start with Thomas Moore, a somewhat elder contemporary of Byron’s, he not only outlived our lordly poet, but held the manuscript of Byron’s memoirs, until pressured by a wide variety of factions, he let it slip into the fire. (For what it’s worth, twice I have sketched out a treatment or draft for stories turning upon Byron, one of which, a mystery novel supposedly, had at its core, the discovery of Byron’s manuscript. I don’t believe there’s any chance of that happening, but then, there was the discovery of Boswell’s papers, I think in the 1920s: miracles can and do happen.)

--Simon Loekle

|

|

As I Please: Simon Loekle |

|