|

Handling the Quixote

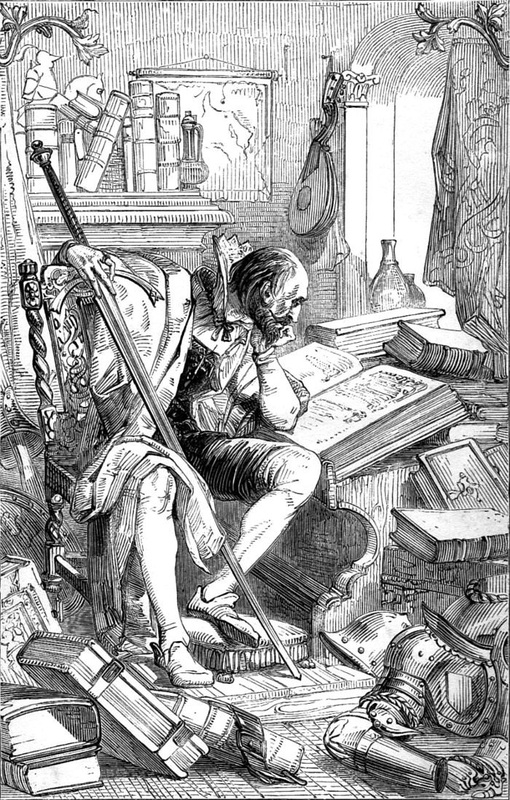

That the Quixote is a pivotal work in Western Literature can not easily be denied. It is granted the honour of being the first novel, and was conceived as a counter-blast to the popular prose romances that were keeping the printers busy. Its primary achievement was to establish "realism" as a foundation for fiction: a world without dragons and wizards and magic potions, a world, as Nabokov memorably remarked, where "sheep stink." It is also an extended prose narrative with comic motives, featuring a madman who accepts as truth the fictions he has read. It is the early XVII century, and Europe is exploring the brave new world of the Americas, while at home, there is the brave new world of literacy: the availability of books, the ability to read, and most important, the skill to discriminate between fact and fiction. The journals of the early voyagers are filled with accounts of what ought to be found: unicorns and monsters and cities of gold; consequently, they were blind to what was really before them. How Quixotic! |

The first part of the Quixote was published in 1605, to great success; we have reports of Spanish nobles falling off their horses for laughter. It was soon an international laugh-riot sensation; an English version by Thomas Shelton was published in 1612, an early example of the translation of a contemporary work into English. More to our point however is the rather surprising proposition that this book we call The Quixote is itself a translation, from the original Arabic. By presenting the fiction that the reader is one step away from the original, Cervantes introduces his next great innovation: the ironic. Cervantes' commentary on the work of Cide Hamete creates a shifting perspective, for the book before us is now no mere simple narrative, but something that has been handled at least twice (and if we are handling an English translation, thrice). In other words, Cervantes has introduced literary criticism into the narrative form, as can be seen explicitly in the book burning scene early on in the Quixote (where a romance by one Miguel de Cervantes is spared the flames). Through the course of the XX century, this ironic perspective becomes quite prominent in fiction: Joyce, of course, and one of the Quixote's greatest champions: Borges. We are more accustomed now to accept that we are reading writing about reading: it is a stance we can trace back to Cervantes. Considering the unhappy history between the Moors and Spain, this is really a rather stunning display of internationalism!

Sentimental Dangers The Man of La Mancha bears as much resemblance to the Quixote as I to Hercules. Do not speak of it again. For our battered and bruised hero, "to dream the impossible dream" would have been incomprehensible: he does not recognize the impossible: he's a loon! Quixotic, tilting at windmills, charging at sheep: pointless battles, the Quixote opens with broader humour, the poor old guy gets quite the thwacking. The pairing of a madman and a fool (so different from the almost contemporary King Lear) creates a comedy of talking at cross-purposes, the knight so well read, his squire virtually illiterate with an inexhaustible supply of proverbs: mocking the pointless repetition of received "knowledge" in the face of the hard facts of the world. But I suspect that Cervantes began to grow fond of the two as he scribbled away, somehow between them a truth emerges. Certainly, as we read on, we become fond of them, so ill-suited to the world, so well-matched with each other. We watch them develop from simple figures of fun to characters who have substance and shadow: the reader lends support and understanding: it is one of the more noble things a novel can accomplish, to teach us to care. Not the sole purpose of a novel, or else it is merely sentimental drivel. Madame Bovary is not a "love story" nor a tract of "women's liberation" — Flaubert described Emma as a "female Quixote," and her misreading of romance novels and fashion magazines leads to her self-destruction. Bovary could be called a satiric tragedy, as we are moved to "pity and terror" in the classic definition, while aware of the limitations time and place have imposed upon her. To turn from Flaubert to Cervantes makes all the more remarkable the subtle yet complicated demands the Quixote makes upon the reader. There is, admittedly, a good deal "old fashioned" about the Quixote, its mulish pace and sprawling scope. But there is much that is quite modern, still worth attention, four centuries later. --Simon Loekle |

|

As I Please: Simon Loekle |

|