|

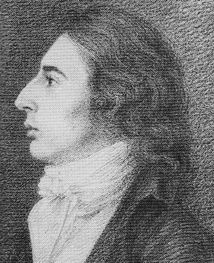

COLERIDGE

. . . I am a Starling self-incaged, & always in the Moult, & my whole Note is, Tomorrow, & tomorrow, & tomorrow. The same causes that have robbed me to so great a degree of the self-impelling self-directing Principle, have deprived me too of the due powers of Resistance to Impulses from without. If I might say so, I am, as an acting man, a creature of mere Impact. "I will" & "I will not" are phrases, both of them equally, of rare occurrence in my dictionary. —This is the Truth—I regret it, & in the consciousness of this Truth I lose a larger portion of Self-estimation than those, who know me imperfectly, would easily believe— I evade the sentence of my own Conscience by no quibbles of Self-adulation; but I confess, that this very ill-health is as much an effect as a cause of this want of steadiness & self-command; and it is for mercy I ask, not for justice. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, spring 1801 ******** . . . O if in addition to the disturbing accidents and Taxes on my Time resulting from my almost constitutional pain and difficulty in uttering and persisting to utter, NO! if in addition to the distractions of narrow and embarrassed Circumstances, and of a poor man constrained to be under obligation to generous and affectionate Friends only one degree richer than himself, the calls of the day forcing me away in my most genial hours from a work in which my very heart and soul were buried, to a five guinea task, which fifty persons might have done better, at least more effectually for the purpose; if in addition to these, and half a score other intrusive Draw-backs, it were possible to convey without inflicting the sensations which (suspended by the stimulus of earnest conversation or of rapid motion) annoy and at times overwhelm me as soon as I sit down alone, with my pen in my hand, and my head bending and body compressed, over my table (I cannot say, desk) — I dare believe that in the mind of a competent judge what I have performed will excite more surprise than what I have omitted to do, or failed in doing. . . .I need not tell you, that pecuniary motives either do not act at all — or are of that class of stimulants which act only as Narcotics: as to what people in general think about me, my mind and spirit are too awefully occupied with the concerns of another Tribunal before which I stand momently to be much affected by it one way or other. Samuel Taylor Coleridge Letter to William Sotheby 9 November 1828 |

. . . Last Sunday I took a walk towards Highgate and in the lane that winds by the side of Lord Mansfield's park I met Mr Green our Demonstrator at Guy's in conversation with Coleridge — I joined them, after enquiring by a look whether it would be agreeable —I walked with him at his alderman-after-dinner pace for near two miles I suppose. In those two miles he broached a thousand things — let me see if I can give you a list —Nightingales, Poetry — on Poetical Sensation — Metaphysics — Different genera and species of Dreams — Nightmare — a dream accompanied with a sense of touch — single and double touch — a dream related — First and second consciousness — the difference explained between will and Volition — so many metaphysicians from a want of smoking the second consciousness — Monsters — the Kraken — Mermaids — Southey believes in them — Southey's belief too much diluted — a Ghost story — Good morning — I heard his voice as he came towards me — I heard it as he moved away — I had heard it all the interval — if it may be called so. He was civil enough to ask me to call on him at Highgate.

John Keats ******** . . . The good old man, he was now getting old, toward sixty perhaps; and gave you the idea of a life that had been full of sufferings; a life heavy-laden, half-vanquished, still swimming painfully in seas of manifest physical and other bewilderment. Brow and head were round, and of massive weight, but the face was flabby and irresolute. The deep eyes, of a light hazel, were as full of sorrow as of inspiration; confused pain looked mildly from them, as in a kind of mild astonishment. The whole figure and air, good and amiable otherwise, might be called flabby and irresolute; expressive of weakness under possibility of strength. He hung loosely in his limbs with knees bent, and stooping attitude; in walking, he rather shuffled than decisively stepped; and a lady once remarked, he could never fix which side of the garden walk would suit him best, but continually shifted, in corkscrew fashion, and kept trying both. A heavy-laden, high-aspiring, and surely much-suffering man. . . Thomas Carlyle "Coleridge at Highgate" . . . Nothing can convey stronger indications of power than his eye, eyebrow, and forehead. Nothing can be more imbecile than all the rest of his face. . .

Robert Southey ******** "Pourtant, pour Monsieur Coleridge, il est tout à fait un monologue!" Madame de Stael |

|

"The Old Navigator"

. . . From what I can gather it seems that The Ancient Mariner has, on the whole, been an injury to the volume; I mean that the old words and the strangeness of it have deterred readers from going on. If the volume should come to a second edition, I would put in its place some little things which would be more likely to suit the common taste. . . William Wordsworth, letter to Joseph Cottle 24 June 1799 ******** Genius has here been employed in producing a poem of little merit. Robert Southey Critical Review October 1798 ******** . . . I cannot refuse myself the gratification of informing such Readers as may have been pleased with this Poem, or with any part of it, that they owe their pleasure in some sort to me; as the Author was himself very desirous that it should be suppressed. This wish had arisen from a consciousness of the defects of the poem, and from a knowledge that many persons had been much displeased with it. The Poem of my Friend has indeed great defects; first, that the principal person has no distinct character, either in his profession of Mariner, or as a human being who having been long under the control of supernatural impressions might be supposed himself to partake of something supernatural: secondly, that he does not act, but is continually acted upon: thirdly, that the events having no necessary connection do not produce each other; and lastly, that the imagery is somewhat too laboriously accumulated. Yet the Poem contains many delicate touches of passion and indeed the passion is everywhere true to nature; a great number of stanzas present beautiful images, and are expressed with unusual felicity of language; and the versification, though the metre is itself unfit for long poems, is harmonious and artfully varied, exhibiting the utmost powers of that metre, and every variety of which it is capable. It therefore appeared to me that these several merits (the first of which, namely that of the highest kind), gave to the Poem a value which is not often possessed by better poems. On this account I requested of my friend to permit me to republish it. William Wordsworth Note on "Ancient Mariner" Lyrical Ballads, second edition (1800) |

. . . I am sorry that Coleridge has christened his Ancient Mariner, a Poet's Reverie; it is as bad as Bottom the Weaver's declaration that he is not a lion, but only the scenical representation of a lion. What new idea is gained by this title

but one subversive of all credit —which the tale should force upon us— of its truth! For me, I was never so affected with any human tale. After first reading it, I was totally pissessed with it for many days. I dislike all the miraculous part of it; but the feelings of the man under the operation of such scenery, dragged me along like Tom Pipe's magic whistle. I totally differ from your idea that the Mariner should have had a character and a profession. This is a beauty in Gulliver's Travels, where the mind is kept in a placid state of little wonderments; but the Ancient Mariner undergoes such trials as overwhelm and bury all individuality or memory of what he was — like the state of a man in a bad dream, one terrible peculiarity of which is that all consciousness of personality is gone. Your other observation is, I think as well, a little unfounded: the "Mariner," from being conversant in supernatural events, has acquired a supernatural and strange cast of phrase, eye, appearance, etc., which frighten the "wedding guest." You will excuse my remarks, because I am hurt and vexed that you should think it necessary, with a prose apology, to open the eyes of dead men that cannot see. Charles Lamb letter to Wordsworth January 1801 ******** . . . Mrs Barbauld once told me that she admired the Ancient Mariner very much, but that there were two faults in it, it was improbable, and had no moral. As for probability, I owned that that might admit some question; but as to want of a moral, I told her that in my own judgement the poem had too much; and that the only, or the chief fault, if I might say so, was the obtrusion of the moral sentiment so openly on the reader as a principle or cause of action in a work of such pure imagination. It ought to have had no more moral than the Arabian Nights' tale of the merchant sitting down to eat dates by the side of the well, and throwing the shells aside, and lo! a genie starts up, and says he must kill the aforesaid merchant, because one of the date shells had, it seems, put out the eye of the genie's son. Samuel Taylor Coleridge Table Talk 31 May 1830 ******** STC habitually referred to The Ancient Mariner as "the Old Navigator." SL |