|

Daniel Defoe (1660 - 1731) is certainly one of the most prolific authors in English; scholars have authenticated hundreds of works that flowed from his pen; his earliest extant work was published in 1688; the novels, for which he is best known (such as Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders and Colonel Jack) were written during the astonishingly productive last dozen years of his life. A quick look at some of his titles reveals an extraordinary diversity of material: The True-Born Englishman (1701), a long satiric poem in heroic couplets that proved such a success Defoe referenced it in subsequent publications ("by the author of The True Born Englishman"); The Complete English Tradesman (1725), a how-to book for commercial prosperity; A Tour Thro' the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724); between 1704 and 1714, he wrote and published, three times a week, The Review. If the urgency of his topical papers has diminished over time, it should not be ignored that free speech was not yet a widespread notion. A satiric essay, The Shortest Way with the Dissenters (1702) backfired: he was arrested, and served time in prison, and spent two days in the pillory. Fortunately, the old custom of cutting off the ears of a pilloried victim had been abandoned. It was the Tory minister, Robert Harley, who engineered Defoe's release — that Harley who played so key a role in the career of Jonathan Swift. Though Defoe had been an active writer since at least 1688, it had been a secondary occupation to his various commercial enterprises. His stay in prison caused his business to collapse, and upon his release, he would earn his keep by writing, initially under the protective supervision of the Tory administration. Swift, you may recall, converted from Whig to Tory when he deemed he had been mistreated, he became a hardliner, and upon the collapse of the Harley Administration assumed a kind of exile in Dublin. Defoe was no less political, just not so partisan. This fundamental difference between the two serves as a key to understanding the special genius each possessed. Crusoe's exile consists of reconstructing the comforts of British society; Gulliver's social contacts make him all the more an exile from any comfort.

Defoe's title as "father of the English Novel" could be disputed, but not for long. Certainly, any account of the development of English prose fiction must offer more than a mere tip of the hat to Thomas Nashe, who, like Defoe, had made his mark as a controversial essayist, and whose first steps towards the novel offered an insider's account of the underside of London life. Nashe wrote and died before the Quixote appeared: but note the fundamental realism of his prose. The essential premise of the early novel is that it offers a "true account;" Cervantes winks but maintains a straight face in offering his history. Defoe never seems to acknowledge this irony in his fiction, and indeed, his use of first person narrative cements the illusion of actuality. In this regard, Defoe is more a descendant of Nashe than Cervantes. As for Henry Fielding, also called a "father of the English Novel," his notable contribution to the form was the invention of the "clockwork plot" but in the pursuit of accuracy, he consulted the almanac in order to get the details right for Tom Jones. |

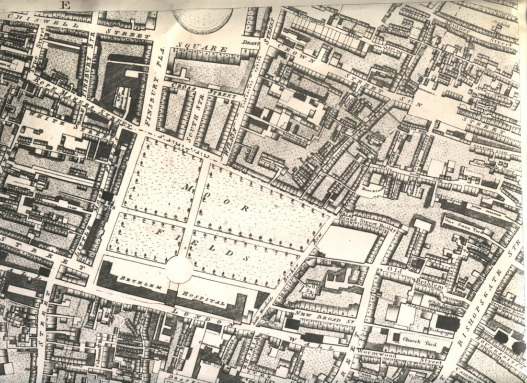

Accuracy of detail is Defoe's special talent, even if, like any good story teller, he might overlook or embellish a fact in the interest of narrative. He interviewed Alexander Selkirk for Robinson Crusoe; for lack of any evidence to the contrary, the Journal of the Plague Year (1722) is the result of independent research, he had no manuscript before him to copy and alter, but a vivid imaginative comprehension of urban experience. The plague swept through London in 1665, when Defoe was five years old: the book is something far more than memorial reconstruction. The grand tour through Great Britain was based upon his many trips around the nation as an agent for Whig and Tory administrations; his commercial career took him to France and Holland (as a sot-weed factor, or tobacco merchant), perhaps no writer of the time was better qualified to give advice to tradesmen. His work combined facts and fictions long before Truman Capote and Norman Mailer claimed to have invented the form. He was, in many ways, the first investigative reporter. By 1700, the career as a professional writer had been established, but commercial success was something else again. Defoe knew what would sell, and even provided his readers with works they had not suspected they wanted. His considerable output produced a considerable income, as we may judge from the property he owned (circa 1724), but a happy ending was denied him. He divested himself of his goods and deeds in the spring of 1730, and spent the summer in hiding. He died in April 1731 in Ropemaker's Alley, Moorfields, adjacent to the Bethlem Hospital, not far from the Farthing Gate to Grub Street. How this came about remains a mystery, but perhaps in the end, Defoe could not resist one more good story.

|

|

As I Please: Simon Loekle |

|