|

Dante’s Comic Relief (Hell 21 & 22)

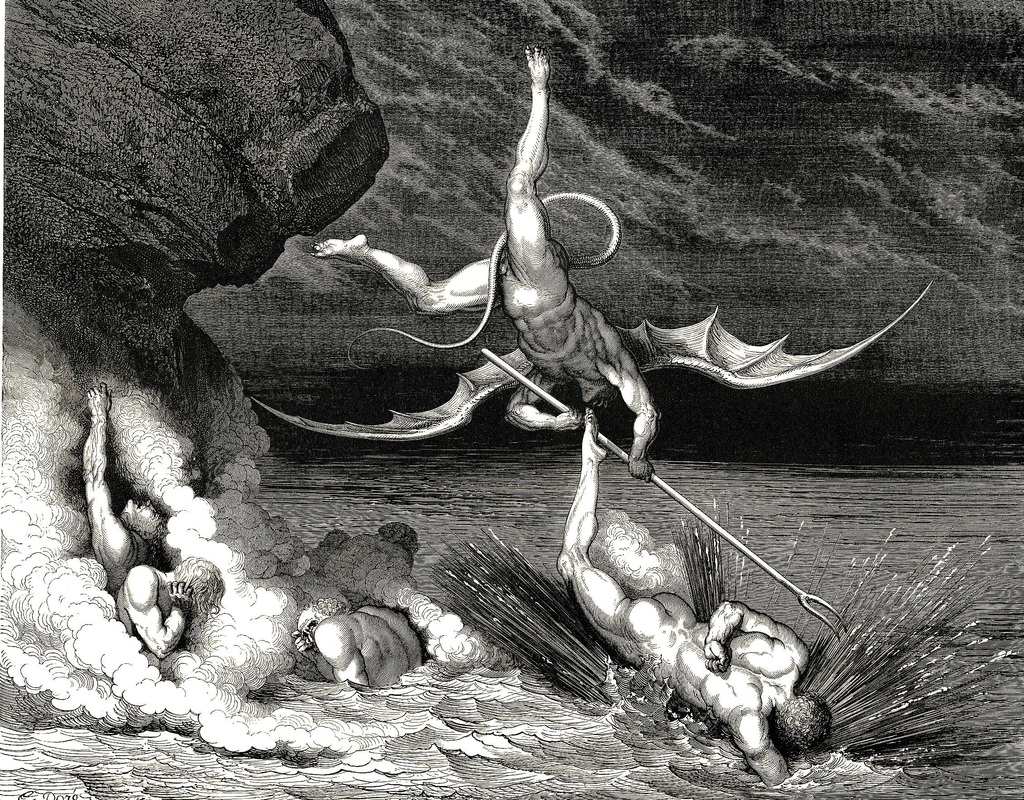

A great many actualities uphold the supreme fiction of Dante's comedy. A key feature of the traditional critical apparatus which accompanies the text (and which ideally should appear at the foot of the page) is the identification of the people we meet. The notes also explain theological and philosophical assumptions, and elucidate literary and historical references. The divine encyclopaedia. Time: 7 AM Holy Saturday 8 April 1300 Dante offers comic relief before descending to the grimmer ghettoes of Hell. Earlier on their way, Virgil had warned Dante against feeling pity for the damned — this after Dante succumbed in face of the punishment suffered by Francesca da Rimini, undoubtedly the most pathetic of all sinners. It is best to remember that the severity of hell has its counterparts in the upward mobility of Purgatory and the glories of Paradise. I have occasionally encountered readers who feel that Dante has a mean-spirited sadistic streak, and though he is responsible for the position and punishment of the sinners, the Comedy is anchored to the theological precepts of its time, the close of the XIII century. An excellent example of Dante's distance from strict adherence to church policy is the punishment of the sodomites, or homosexuals. A lesser man than Dante might easily have engaged in vindictive and demeaning abuse of these condemned; instead, the Poet walks by the side of an old friend and mentor, Brunetto Latini. In theory, if the soul reaches Purgatory, it can be assured that Paradise is its destination, and to find oneself in Paradise is a guarantee of an eternal dwelling place. But who are we to say that at the final judgement God may not show mercy to Francesca, and Brunetto. Or the billions born outside christianity. Of course, Dante can not undermine the moral system of hell, and to this end introduces the buffoonish demons who guard sinners themselves unlikely to arouse much sympathy: the grafters. A good strategy: it allows us to enjoy both the besting of the demons and the just desserts of divine justice — those who on earth lived by the greased palm find themselves in hell's pool of boiling pitch. On Nabokov's principle "laughter is the best pesticide," demons, as comically contemptible, were often the butt of popular entertainment. Buffoon, from boufon, the grotesque mode of clowning: distortion, deformity, and at times an eloquent vulgarity. The bumcrack sounded at the close of Canto XXI (that most esteemed example of a fart for Art's sake) alerts us to the demonic come-uppance. Dante opens the next canto with a personal recollection of war and defeat that shifts to games and contests, what might be called a “negative simile” — never has he experienced the like! — a wonderful transition after the terrifying role-call (xxi: 118 - 123). Binyon englishes the names of the demons, not every translator does so. The demons, no brighter than a pack of hounds, suggest another performance tradition, the comic constable. Dogberry is an example. The ten Malebranche (the Evil-Claws) are the Keystone Kops of Hell. Barrator is not a common word, it comes from the Italian, barrata: a skirmish or wrangle. Ezra Pound always called them grafters. The confidence game was once called grafting, but as the term became more and more associated with politicians (at the close of the XIX century) the criminals changed the spelling to grift. The trumped up charges that led to Dante's banishment from Florence accused him of graft. When Dante refused to return to Florence to plead guilty (!), the sentence was revised to banishment for life, upon threat of being burned alive if caught in the city's precincts. This was in 1302, and Dante was thereafter an exile. The Comedy was the great work in progress during these wandering years; it is said that he put the finishing touches on Paradise days before he died in Rimini in 1321. |

Santa Zita is the patron saint of Lucca, hence the common annotation “a town notorious for political corruption.” Lucca was a centre for the olive oil industry (figuratively, a tool of the grafter’s trade). Santa Zita, ironically evoked by the demon who delivers a sinner, is the patron saint of domestic servants: the grafters practice their craft within the household. Of Bonturo we know no more than the name, but insofar as it drops from the lips of a demon, we are inclined to believe he is no innocent. Similes [My marginal sign for simile is ∆: the fulcrum.] The lengthy description of Venetian winter industry which opens Canto 21 is an example of largescale proper activity, reparative maintenance, as opposed to the private “self-maintenance” of the sinners. A number of household images (watchdogs, the cooks) follow before we are introduced to the constabulary demons. By “individualizing” some of them, Dante makes the whole pack real. Canto 21 shows Dante afraid (even Virgil notices), but after the extended “negative simile” that opens #22, he speaks proverbially: “In the church with saints, with rascals in the pot-house bide.” (Binyon) An apt proverb is an occasional simile. Perhaps my favourite simile in Hell, sinners like frogs peeping their eyes above the pitch in fact follows a no-less striking simile: like dolphins leaping from the sea, the sinners seek relief. Now, the frogs: another creature that lives in two worlds (water and air) but slipperier than the dolphin. Dolphins inspire wonder. Frogs are laughable. A neat juxtaposition. DOG TAGS Herewith the demonic rolecall of Canto 21 (118 – 123) in the original and as Englished by Laurence Binyon. Alichino Hellequin Calcabrino Frostyharrow Cagnazzo Dogsnarler Barbariccia Beardabristle Libicocco Furnacewind Draghignazzo Dragonspittle Ciriatto Swinewallow Graffiacane Houndscratcher Farfarello Farfarel Rubicante Scarletfury Whether the Italian or the English, bound to attract attention at the local dogrun. -Simon Loekle |

|

As I Please: Simon Loekle |

|