|

STYLE: NARRATIVE (OLD)

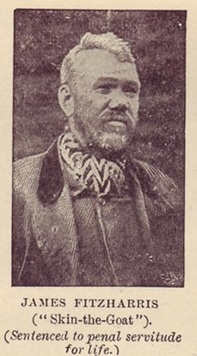

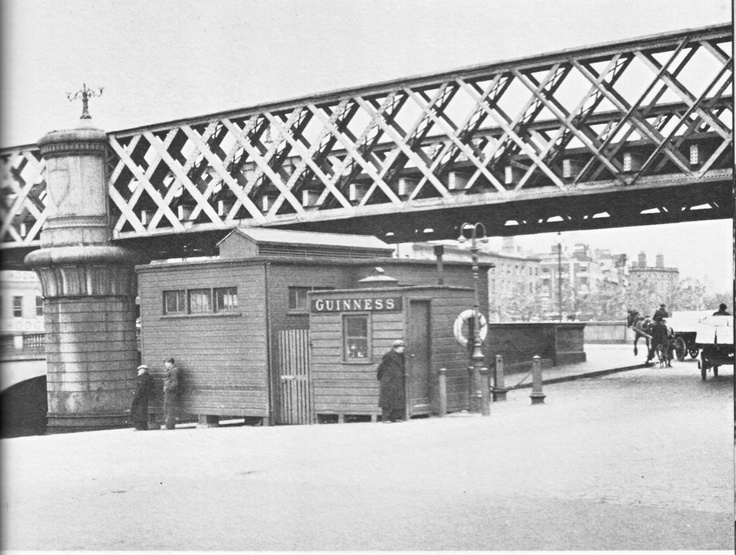

It may be that the style of Eumaeus, “Narrative (old)” has received more notice than its fellows, (Telemachus) “Narrative (young)” and (Calypso) “Narrative (mature)”. Certainly, the restoration of the exclamation points to Telemachus in Hans Walter Gabler’s 1984 edition of ULYSSES was a worthy emendation and proved a veritable fountain of youth. Notably, the style of Eumaeus is defined by its faults; “old” has sometimes been modified with “exhausted,” “weak” and “weary.” The rambling narrative, compounded of clichés and marked by syntactical uncertainty, was described by Hugh Kenner as something Bloom himself might write. This is illuminating but not gospel. Granted, Bloom undoubtedly imagines writing to be a far simpler task than it is (if done well), but “under all the circs,” being in the company of poet-professor Stephen Dedalus, and the whispered likelihood that the man behind the counter is Skin-the-Goat, Bloom simply would not dwell so much upon himself. If the episode represents the inspiring events for something to be called My Experiences in a Cabman’s Shelter, (xvi 1229) frankly, I don’t believe Bloom would get “much forrader than the title.” Kenner alerted us to the role of the non-literary narrator in this final unravelling phase of the novel. By this point (16 of 18), the reader of ULYSSES should have learned a thing or two about style — enough to recognize bad writing. Bad writing can be found in the interpolations to the Nameless One’s narrative Cyclops, and the first half of Nausicaa displays problems with punctuation that we will find in Eumaeus, but Nausicaa is governed by the genre of the Lady Novelist, while the troubled prose of Eumaeus, by far the worse of the two, is riddled with rookie mistakes. To turn over the reins of narrative to one with so few professional skills is a sign that The Novel is over, and perhaps not only ULYSSES. Particularly foreshadowed here is the elastic syntax of Finnegans Wake.

“Proper words in proper places is the very definition of style” declared Jonathan Swift, and it is by ignoring this wherein the “badness” of Eumaeus lies. As Michael Groden has noted (Ulysses in Progress, p. 53), unlike the interpolations of Cyclops, or the sequence of styles in Oxen of the Sun, the prose of Eumaeus is not a parody. The Narrator sincerely believes this is better than passable prose, that this is what writing’s about: breezy, informative, personable. Sincerity is often a factor in bad writing, insofar as it overlooks the arts of persuasion, insofar as it neglects the science of editing. I suspect that by 1922, when Eumaeus first appeared in the Shakespeare & Co ULYSSES, this particular species of bad writing was already perceived as old-fashioned, but elements can still be found in the public posturing of a Letter to the Editor. The bad habits of Eumaeus are first exhibited in old man Deasy’s letter to the press. HOMER ASIDE Eumaeus is featured in three successive books of the Odyssey, when Homer is engaged upon such narrative duties as getting his hero home, reuniting father and son, and presenting the situation at Ithaca. There is a narrator “tic” that runs through this portion of the Odyssey, the repeated reference to “swineherd Eumaeus.” In Robert Fitzgerald’s post-Joycean translation, this is rendered as “O my swineherd” which redirects our attention to the obvious affection and respect Joyce’s narrator bears for Leopold Bloom. Odysseus is still disguised, but Bloom is recognized as a hero. In this episode, Mr Bloom is primarily engaged in “shepherding” Stephen. |

Though Bloom does double duty here as hero and herder, there is a sailor home from the sea, who ironically fulfils earlier allusions to the Ancient Mariner, and also embodies the less truthful aspects of Odysseus. There is little to be said concerning the account of Simon Dedalus sharpshooter; unlike Shakespeare and Murphy, Dedalus is not a common name. Like the Ancient Mariner, the seaman Murphy is compelled to talk, though his tales sag towards banality. Bloom’s doubts are duly noted by his admiring Narrator. There is some added confusion, resulting from Gabler’s editorial decision, in accordance to the Rosenbach manuscript, to alter Murphy’s initials from W.B. to D.B. It is clear that Joyce originally wrote D.B., but it is no less evident that from 1922 until Gabler’s 1984 edition, the name was rendered W.B. Murphy. Michael Groden reports that the typescript for Eumaeus came directly from what we now call the Rosenbach manuscript, and that the typist left blanks when the material seemed too shocking or offensive to type. Whether or not the initial change was made at this level, Joyce had to go over the text closely to restore dropped elements. In the long run, he never bothered to anchor the initials. I prefer “WB” as a sly and almost private joke on Yeats, though I admit its subtlety is such as to have no grand effect on the “meaning” of Ulysses. A student pointed out to me the story of “D.B. Cooper” — which of course Joyce would not have known. “B” was a later addition: the man on the flight was simply Dan Cooper. (This has nothing to do with ULYSSES, a great deal to do with the authority of the Press!) WRITE STUFF

Though demonstrably grammatically incompetent, the Narrator of Eumaeus is aware of his duties, and, accordingly, is issued the standard toolkit of the trade: he can report the unuttered thoughts of Bloom and Stephen, and he has occasional (albeit flawed) access to background information, such as the curiously muddled genealogy of “Lord John” Corley. Our Narrator aspires to magazine writing; he seizes upon the Corley story because he is sure it will prove a crowdpleaser. It falls into the general category of local history (we encountered a pair of amateur historians in Wandering Rocks, Ned Lambert and the almost invisible Reverend Love ) and where there exists a small town newspaper, there’s a good chance that something like a local historian still sees print. The Narrator attempts to correct his Corley account, but winds up wondering if perhaps “the whole thing wasn’t a fabrication from start to finish.” Corley’s bloodline, or the Ancient Mariner’s account of Simon Dedalus, sharpshooter are histories undermined by disbelief, set in blandly naïve prose. ULYSSES is an historical novel, but the precision of detail regarding June 16, 1904 is countered by a frequent haziness of a longer historical perspective — Bloom, for example, consistently gets wrong the date of the Phoenix Park murders. Perhaps “history is to blame” that we so easily forget our history. Had I studied at Cambridge I might more succinctly address the questions of grammar that abound in Eumaeus. Phrases dangle, words collide, metaphors are mixed. Early in the episode there is an example of what I call “collision” in the side by side occurrence “away near” (xvi: 09). A comma placed between the terms would lessen the “offence” but it is enough to note that these are words not commonly placed next to each other. A different kind of “collision” occurs in slow motion (as I believe Hugh Kenner called it) : “. . . evidently there was nothing for it but put a good face on the matter and foot it . . .” (xvi: 32). Bloom does a lot of talking throughout the episode, but his remarks are regularly presented in the manner of the Narrator. The other speakers are presented more or less verbatim. The effect is almost the opposite of Cyclops: here, the Narrator is clearly fond of Bloom, and the episode is marked by vernacular interpolations. The dissolution of style and narrative shows Joyce’s preference for the anti-climax (the three episodes which open ULYSSES provide the anti-climax for A PORTRAIT). The Narrator of Eumaeus (and perhaps Bloom himself) may think this episode to be the striking accomplishment of the day, but Joyce is winding down, forward momentum of Narrative is no longer Joyce’s concern. The next episode, Ithaca, demonstrates that there is plenty still to learn about Bloom, and the uncorseted words of Penelope, besides presenting one of the most fully realized characters in all literature, fixes a few facts about our Dublin Ulysses. The admiration the Narrator of Eumaeus lavishes upon Bloom may be an impediment to knowledge, but we do get the story of Parnell’s hat, and the more disturbing information (easy to overlook considering its source) that Blazes Boylan and Leopold Bloom met for a drink at The Bleeding Horse. “All has not been told and never shall be.” (Samuel Beckett, The Lost Ones, ¶ 12). |

|

As I Please: Simon Loekle |

|