|

MEET MR MAUBERLY

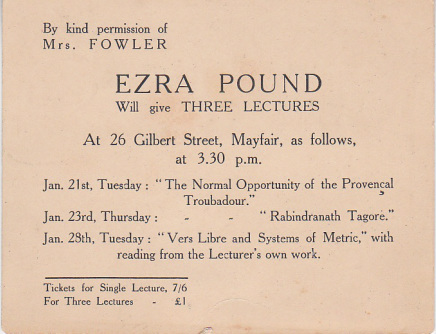

I suspect fifty years ago a college student may have first encountered Mauberly in the company of one Mr Prufrock, followed by a quick tour of the Wasteland, and so conclude a survey course which had hit some of the high points of poetry in the English language. By the early 1970s, this traditional approach to literature had come under attack, and had been largely replaced by the narrow views of special interests. The pairing of Prufrock and Mauberly recalls the combined efforts of Eliot and Pound, but beyond the impressive triple-barrelled names (J Alfred Prufrock; Hugh Selwyn Mauberly) they've not much in common. Nevertheless, when I dutifully enrolled in a course on Pound & Eliot, I discovered that a number of my fellow students were labouring under the misconception that Mauberly was Pound's "Homage to T Sextus Eliot" — a point that hung fire, as Pound's Propertius was not part of the syllabus. How to Read Hugh Selwyn Mauberly occupies an odd spot among the works of Ezra Pound. It is accorded all due respect, it has been anthologized, annotated and analyzed, and then (with an accompanying note declaring it approved by T.S. Eliot) it is returned to the shelf. A quick look at the text, and it doesn't look like Pound: the short lines with the strict left margin suggest a regular and recognizable meter; the eye may also catch some rhymes. Closer examination rapidly sets it apart from the work that cemented Pound's reputation: HSM appears paralytic next to the broad sweep and rapid leaps of the Cantos. HSM is a pivotal piece, Pound called it "distinctly a farewell to London." Pound imagined China, XV Italy, the America of John Adams, to this add his vibrantly reimagined pagan world of Homer and Ovid, but the contemporary scene was not a common subject for him. The period, approximately 1910 - 1920, is more fondly recalled in the Pisan Cantos . The fact of Pound's long residence in London (a period of great accomplishments for the young poet, who turned 30 in October 1915) creates the misconception that HSM is autobiographical, a reading Pound clearly sought to avoid in the very first poem of the suite. The Pisan Cantos are autobiographical, but HSM is a piece of fiction, a modernized narrative poem; in fact, it is an example of that curious subgenre, the novel-in-verse, a category that almost escapes definition. Barrett Browning described her Aurora Leigh as such, and Pushkin's Eugene Oneigin is also recognized as an example of the type. Pound wrote HSM after rereading much of Henry James, a project he began upon the author's death in 1916; in 1922, Pound remarked that HSM was "an attempt to condense the James novel." This tells us how to read the poem. Though now nearly a century in the past, the era is familiar thanks to Merchant Ivory and countless BBC productions. Being able to imagine this background (costumes and sets, so to speak) sharpens the "novelistic" qualities of the poem. Note the satiric motive that aims its gaze at a society whose rituals and manners (again thanks to Merchant Ivory) are familiar, but nevertheless a bit alien, and only slightly less strict than those that governed Jane Austen. The story concerns Hugh Selwyn Mauberly, a minor poet whose career falters and who ultimately "evaporates" from the London literary scene. For my purposes, Part One is brought to us through the agency of an Investigator or Biographer. Poem as Plot We open with a memorial ode for the American poet, E.P, whose brief career in London was dedicated to reviving "the dead art of poetry." (The quote from Villon 'l'an trentuniesme de son eage' provides an approximate date, if we let E.P. stand for Pound.) His efforts fell largely upon deaf ears, but the Biographer was persuaded, and he offers a general overview of England's declining cultural state, concluding with an impassioned indictment of the Great War. It is customary (and understandable) in discussing HSM to proceed poem by poem. However, this undermines the premise of novel-in-verse, dulls the satiric edge, and obscures the difference in narrative tone between the first and second parts of the work. I think the "ode" which opens HSM runs through the first five sections; were this a prose novel with the heft of one by James (400 pages instead of 400 lines), classroom discussion would circle around the crushing weight of the war on London social and artistic life. The Biographer, in effect, dedicates this work to the memory of E.P., before turning his attention to Mauberly, a promising poet who has vanished from London's literary circles. Ezra Pound left London, and burnt his bridges behind him. E.P. dies young. Mauberly's exit amounts to a slow fade. Biography is far from scientific, but a personal role in biography was once much more common than it is today. The grandest example of this type is among the first, Boswell's Johnson, where Boswell is as much a part of the story as his hero. In the XX century, and an example that matches Mauberly nicely, there is The Quest for Corvo by A.J.A. Symons. The Symons book postdates Mauberly by 14 years, but coincidently Symons was an expert in the poetry of the 1890s, a period evoked by The Biographer as he turns his attention now to some who knew the poet. Contacts In contrast to the wartime slump presented in HSM, two earlier periods of English cultural activity are recalled: the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (fl. 1861) and the poets of "The Nineties" (of whom, W.B. Yeats was then and now the best-known). That the names mentioned require annotation is, alas, the point, a symptom of British cultural amnesia. Mauberly is invisible before the witnesses the Biographer summons. The first two of these contacts, the Artist Model and M. Verog, foreshadow Mauberly's ultimate dissolution. Once, each would have been welcome at the kind of soirée we encounter later in HSM. Sixty years ago, she was judged beautiful, and the paintings shocking and scandalous; she's lived to see them museum pieces. As for Monsieur Verog, I have always believed that his obituary was composed in 1905, but subsequently mislaid. With little prompting, Verog offers his memories of the circle he shared with Lionel Johnson and others (which implies, by the way, Yeats, also a member of the Rhymer's Club). |

The next two sources represent the Establishment, but Mr Brennbaum is a special case, due to the notoriety of Pound's antisemitism of later years. Readers now latch on to "The heavy memories Horeb, Sinai, and the forty years" as an early example of this, missing what I believe is the point. Brennbaum, an editor or publisher as I take it, embodies material success, and is "more English than the English." Nevertheless, he too is outside the literary scene. Like Leopold Bloom, Brennbaum is a victim of anti-semitism. (There has been a good deal of work identifying the "originals" of Mauberly, which I have so far ignored, but Brennbaum is always described as "really" Max Beerbohm, which denies Pound the "fictionality of fiction" that is a basic right of the novelist. I have shaved the bulk of Mauberly criticism with Occam's Razor.) Mr Nixon, a careerist and a recognizable villain in the piece, gladly offers the advice "And give up verse,/There's nothing in it." The many historical figures that anchor the poem (Gladstone, Ruskin, Buchanan, Lionel Johnson) are countered here by an allusion to Browning's Bishop Bloughram's Apology, wherein the churchman accounts for his career of hypocrisy. A reference to a fiction within a fiction would have pleased Browning (and Borges) but it also reminds us of how unlike Browning HSM is. This is not dramatic monologue, and the efficiency with which we have been introduced to several characters is often overlooked. The Artist Model's name is lost in a shuffle of actualities; M. Verog is presented in paraphrase. Only Mr Nixon speaks for himself.

The stylist who is neither greatly paid nor widely known is one of my favourite "chapters." I have always found this interview uplifting: he is still working, and he has not compromised. It is self-exile, thirty miles outside London. "Stylist" is not an idle term: it stands as contrast to the "prose kinema" earlier targeted in HSM. The two literary salons, one in the suburb of Ealing, the other organized by the aristocratic Lady Valentine are specimens of a kind of social engagement of which there is no genuine successor. It is the last stage of individual patronage, before the state and corporations took over the responsibility of parcelling out donations to the arts. Remember the premise: a powerfully condensed novel by Henry James. The emptiness of these gatherings is perfectly conveyed. From the introduction, on E.P. and the "tenor of the times," through the seven interviews, we are given the milieu in which Mauberly lives, but not much personal information regarding Mauberly has been revealed. What follows, the Envoi, is something only Pound could make: a contemporary XVII century poem.

So far, the verse has been fairly regular, chiefly quatrains; the rhyme and metre inform the satiric motives and maintain a brisk forward momentum. With the Envoi, Pound turns to the more fluid rhythms of the XVII century; it is Exhibit A for the culture HSM advocates. In the context of the novel-in-verse, I think it recalls a moment shared by E.P, the Biographer and Mauberly. So concludes Part One. I have taken Pound at his word, and "condensed James" does inform the poem. Pound's modernizations included the jump-cut from scene to scene, foregoing trivial novelistic chatter. The Biographer (though it's my own invention) answers the charge that HSM is disjointed and shapeless. And again, this kind of life & letters biography was common, if not standard, when Pound was growing up and on to the 1920s. And finally: Pound writes HSM after several years of having been among the first to read the latest pages from James Joyce. So, grant Pound a little narrative sophistication here: the second part of HSM has a different Narrator, one closer to our hero, but not so kind as the Biographer. Fade to Black The admitted difficulty of the second part of Mauberly is that we keep company with a minor British poet during the period his talent evaporates. It is not just a feature of this novelistic reading that Mauberly is presumed to show talent: it's the traditional take, dating from the poem's publication in 1920. Read as novel, the poem's satiric motives are renewed; the Narrator's diction, inspired with Henry James, glitters and bristles, and while we gain access to Mauberly's "inner life," the syntax holds us at arm's length. Even if we can't place Mauberly firmly among the Modernists, he is inching in that direction. The satiric motive of HSM has two targets: the decline of progressive elements, as represented by Mauberly (it's his "failure of nerve", and not any flaw with "modernist principles") and the implied habitual comforts of standard poetic fare —the sentimental attraction of the Great War Poets, for instance, many of whom had the added advantage of being dead, as dead poets are easier to handle than dying ones. Indeed, HSM, as a parody of the literary memoir, is a bid to establish Mauberly's post-humus fame. The uncertainties we find in the next "chapter" reflect Mauberly's faltering naiveté within the London literary scene, and his incompetence with the skills needed to survive the fierce political juggling of the salon. These are the skills "the Age Demanded" — the skills recommended by Mr Nixon —. In retrospect, the reiteration of Flaubert (and the phrase "the Age demanded" from Part One, HSM) serve as a kind of warning against sentimentality. Flaubert's rigorous and relentless accuracy would not tolerate cheap pathos, while the recalling of phrases from Part One (particularly if my suggestion of a second Narrator is accepted) create a kind of critical perspective (parallax). Mauberly is both fool and poet; he has mastered technique, but has missed the human connections. He imagines, to escape the chilly fogs of London, a sunny spot by the sea, and succumbs to this fantasy, as the doors of literary society close, one by one, against him. The tropical vision of HSM II iv is a jumble of travel books and brochures and posters, Mauberly hasn't followed Stevenson to the South Seas. It is evident that, at the end of HSM, Mauberly is "as good as" dead; whether an actual corpse (caught in the influenza epidemic of 1919) or resident in a lunatic asylum, or an employee in a distant office of Thomas Cook is unimportant.

The final poem, "Medallion," is one poem within HSM that is meant to be seen and read as a poem; a poem by Mauberly himself. Though a shadowy figure throughout HSM, we have received enough information regarding Mauberly to identify "Medallion" as his. Its placement creates a parallel to the Envoi which closes Part One, and (with novelistic logic) refers to the same event. Generally, a poem encountered in the context of a novel will be harshly judged, even if the context is a novel in verse. The poem's there to serve the novel; our judgement of "Medallion" is informed by what we have learned about Mauberly's place in literary society, and his literary models and standards. Simon Loekle

|

|

As I Please: Simon Loekle |

|