|

REMARKS ON FRANÇOIS VILLON

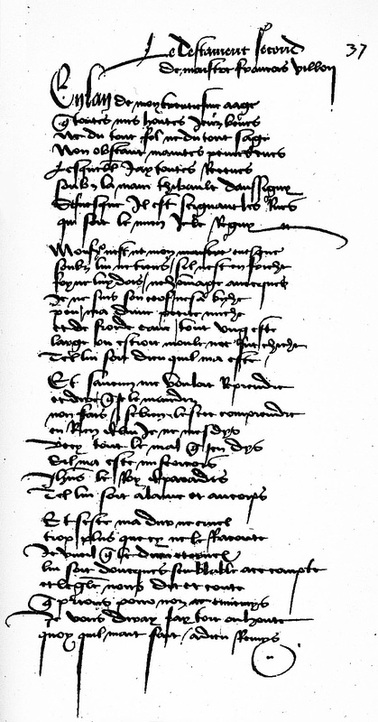

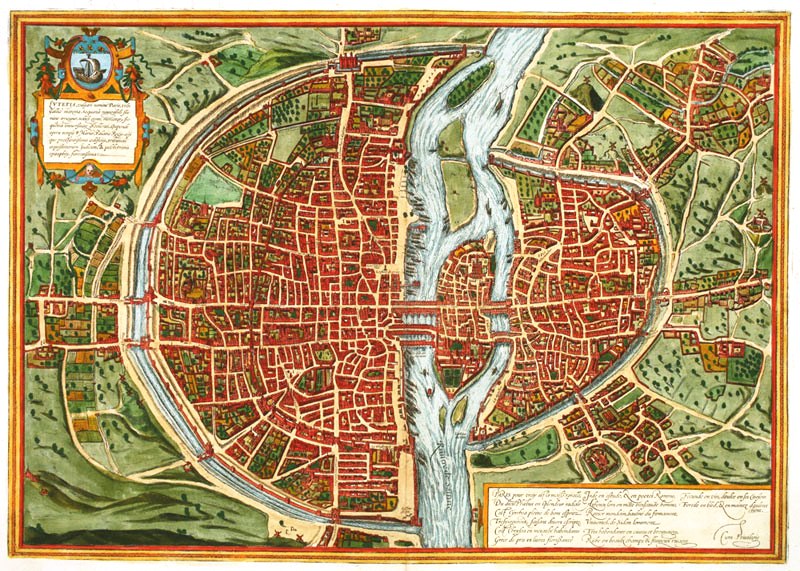

Francois Villon disappeared from written record circa 1463 (aged 30), when he was banished from the city of Paris, after a dramatic reprieve from the gallows. Though Gutenberg's contraption was thumping clanking and squeaking in Germany, the first printing press did not set up operations in Paris until 1470; the earliest edition of Villon was published in 1489. That Villon's reputation survived for nearly 30 years after his disappearance, that it proved strong enough to support a half dozen published collections of his work over the XVI century is his true legacy. It was the literate and literary readership that preserved his words and brought them to the print shop, but he had a reputation among his contemporaries not only for his criminal activities: he was known for his poems. The First Respondents were listeners, in taverns and jail cells and fine chateaux. The Legacy was written (I think quickly) in 1456 just before the poet fled Paris, and it is in part a farewell to his native city. The specific places and people underscore its satiric motive; if the topical humour falls flat after 500 years, the energetic bite of the verse still makes its mark. Over the next four years on the road, The Legacy, it may reasonably be supposed, served as a kind of ticket or calling card, as it displays his skill in a long poem (a traditional ambition of poets). The satiric parody of the Last Will (popular since the days of the plague) spared Villon the demands of narrative (which, somehow, Villon does not seem temperamentally suited for). The format is obviously flexible, and if Villon presented it along the way, it is easy to imagine his touching up the text with local references. That The Legacy is a work of hardboiled irony is palpable, though how the irony works through the poem is more difficult to grasp. Over the centuries, virtually all of the "heirs" have been identified, but we have lost the immediacy of the reference, and must bear in mind that Villon is engaged in presenting "the thing that is not." It is also clear that The Testament is unquestionably the masterpiece: the interludes of ballades and rondeaux enrich the poem, providing human details and warmth, and better exposing Villon's humours. The two poems cover much the same territory (behind or to the East of Notre Dame); some of the "heirs" in the first are "re-gifted" in the later. I can not help but think that the later work was a conscious revision of the first. DANTESQUE REFLEXIONS

There is apparent literary ambition in The Legacy: its tripartite structure may not be a Dantescan reference (triads were common in medieval thought) but the morbid motif of The Legacy (albeit satiric) parodies the three realms of the Afterlife, with The Legacy's first part, "Love's Martyr" presenting Hell (on earth); the second, the bequests, the Purgatory of addressing this world's obligations; and third: the seeming abstract philosophical ponderings of the conclusion offer a parody of the intellectual complacency of paradise. I dare say Villon did not know Dante: these were common formats of his age, and Villon uses them to provide a shape and context for the sprawling nature of the bequests. But it also indicates that Villon was alert to the possibility of a literary readership, and considering the brief life expectancy of the period (something of which Villon was especially aware!), it bolsters my opinion that Villon was anxious to make his mark and address a (somewhat) broader audience. Even so, The Legacy has, at times, been taken too literally, so that Villon is criticized for his feeble handling of philosophical precepts, or accused of self-pitying whining in the "Love's Martyr" section. "Love's Martyr" is quite different from Villon's embittered detachment regarding Fat Margot, and there is a repetitiveness to the section which recalls a cockroach scuttling round and round, trapped at the bottom of a bowl. But as I have already imagined The Legacy as something recited along the road, perhaps this repetition is the shadow of performance practice, a set of stanzas to choose from, allowing Villon a smidgeon of variety in his presentation. I'm not prepared to go to the rack on this point, but I do think that the peculiar lively and prickly quality of Villon's poems hangs from the useful friction of poetic ambition and performance experience. This perspective somewhat demotes a stricter auto-biographical reading of the works by emphasizing the living working writer. As it happens, Villon's last decade is well documented in criminal court records. And how little direct use Villon makes of these experiences! (The Hanged Man's Ballad is an independent poem, outside both The Legacy and The Testament.) His subject is built upon the actualities of life at liberty — though, in the main, it's a record of wasted liberty. (Still, life of any sort was better than the miserable suspense of prison conditions. Starvation was customary; torture, the option of the jailers.) "Fat Margot" amply demonstrates that Villon doesn't care a plugged nickel how future readers may judge him; neither does he overtly play the pathos card of prison. In the history of love poems, there are not many happy couples; some sort of separation is needed to motivate the poem, whether distance, or temperament, or class. In the two centuries or so before Villon, there were two ways to approach the subject: the beloved was too good for the poet, or the beloved was (unfortunately) involved with someone other than the poet. The device of referring to the beloved as an angel is an old one, but Dante takes this a step further and frankly places Beatrice in the company of angels. Villon makes no effort to disguise Margot's profession, though in turning the standards upside down and inside out, he manages to present a perversely contented couple. Dante takes the love poem one step beyond; Villon one step below. A better point of comparison between Dante and Villon is the realism each employs. Granting that Villon is working within a smaller frame of reference than Dante, the Comedy and Villon's legal satires are chock full of historic figures ("actual" humans). Thanks to Dante's supreme narrative skill, annotation expands our understanding of his poem, while notes for Villon only further ground his poems in the specifics of his time and place. Historic realities are but one strand in the mighty cable of the Comedy, but it is difficult to proceed far in Villon without acknowledging the facts, no matter how they are distorted by his ironic stance. In this regard, Villon's works are exceptionally site-specific, in that the house signs and tavern signs that he so generously bequeaths, must have been actual locations known to his first respondents. |

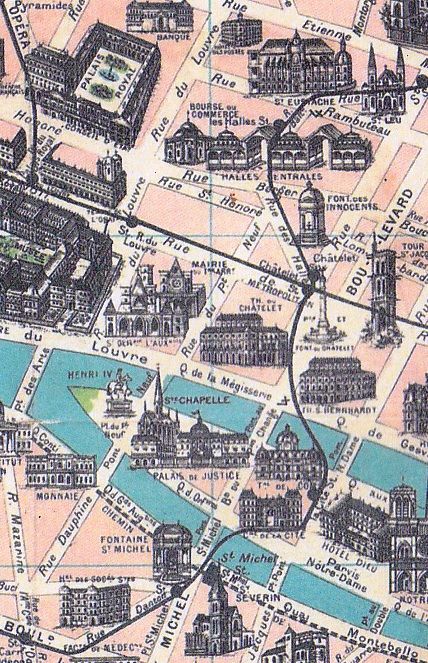

Alas, there's no Thom's Directory for Paris 1456, but the combination of criminal and historical records convinces me of the realities of the text. The reference to Saint Jacques anchors The Legacy to one specific site at least, the meat-packing district of Paris (Saint Jacques, among other things, was the patron saint of butchers: Saint Jacques "the cut up", not a reference to his amusing antics but the means of his martyrdom; a church in his name was built within a century of Villon's death: all but its tower was destroyed in the Revolution; it's now a stop on a tour of the fourth arrondissement, where once stood the Bastille). Such a neighbourhood was not for the tony; rather, an ever present reminder of brutality and mortality. The squeamish may now more readily perceive the underlying hellishness of Villon's satire.

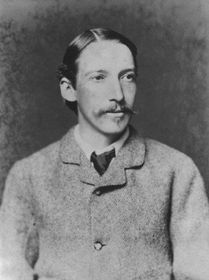

THE THING THAT IS NOT From John Payne's translation of The Legacy (1878): Item, this trust I do declare For three poor children named below: Three little orphans lone and bare, That hungry and unshodden go And naked to all winds that blow; That they may be provided for And sheltered from the rain and snow, At least until this winter's o'er. This stanza wonderfully displays the profound difficulties in handling Villon for both translator and reader, for surely it led to an outburst of laughter and applause among the First Respondents when these pathetic orphans are identified as three of the wealthiest men in Paris. Annotation takes care of the problem, but because it is more convenient to print notes at the foot of the page or the back of the book, rather than in the margin, immediacy is lost. If the translator is willing to undergo the "up-dating" of the entire poem (going a step beyond the occasional useful anachronism) perhaps Mssrs Colin Laurens, Jehan Moreau and Girard Gossain might be replaced by Bloomberg, Romney and Gates, but this solution seems roughly equivalent to the habitual modern dress performances of Shakespeare. It requires skill to get beyond the dead-pan of the printed page: as important as anything to the art of poetry is the just pause to accommodate shifts in tone and emphasis. Perhaps it seems unnecessary to harp on Villon's satiric edge, but his best known refrain Mais ou sont les neiges d'antan? (famously translated as "Where are the snows of yester-year?") is often subjected to a sentimental turn, as though Villon is expressing nostalgic fondness for snowdays at school, when in fact he is noting the vanity of human wishes. (The ballad in question is one of a set on this theme in The Testament.) Villon knows that the snow leads to the mud of spring, but what of the blossoms of yester-year? Might not this seem a more suitable image in a poem that names so many long gone beautiful women? Instead: harsh barren winter, when the rooms in Paris were cold and dark and (with luck) sooty; the winter of 1450 was so severe, a pack of wolves, said to number over 40, entered the city in search of food. Villon is not a sentimentalist. On a snowday or a sickday or perhaps a "movie for a rainy afternoon" when weather cancelled baseball, I was introduced to Villon by the Hollywood treatment, If I were King, starring Ronald Colman. It's a fun movie, but not especially factual, and I don't believe a single line of Villon's made it to the screenplay (to which Preston Sturges contributed). I am also fond of The Beloved Rogue, a silent movie starring John Barrymore, which is no more accurate. IMDb lists a score of productions loosely based on Villon's career, beginning with a 1914 serial, and including television plays in the early 1950s: one starred Douglas Fairbanks Jr and another, Errol Flynn. To bring a poet to the silver screen (and/or what was once called the small screen), never a strong suit of Hollywood, deserves a round of (feeble) applause, and I suspect these treatments all descend, in a roundabout way, from a story by Robert Louis Stevenson, "A Lodging for the Night." A rogue, a prankster, an "irreverent dog" to use a phrase of RLS, a swashbuckler ("a swaggering bravo or ruffian; a noisy braggadocio" OED). The poems are, at best secondary, and a distant second at that. The criminal activity is presented as boyish fun, the poverty smoothed over. No anger, no bite, no motive remains. To be fair to RLS, read his essay on Villon; to be fair to Villon, read him!

Simon Loekle |

|

As I Please: Simon Loekle |

|