|

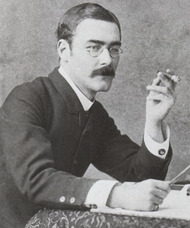

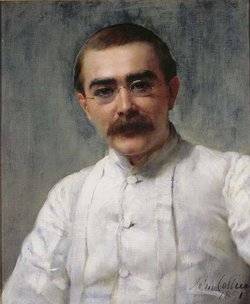

It is a pity that George Orwell’s essay on Rudyard Kipling should have been a review of the volume, A Choice of Kipling’s Verse, made by T.S. Eliot. No doubt Orwell would have raised similar questions had he considered Kipling’s prose, but he also would have avoided such statements as “during five literary generations every enlightened person has despised him. . .” While I can’t make a point for point catalogue of “influence,” it is certain that Kipling was among the writers Eric Blair read while growing up, and he might have noticed common ground. Both had been born in India, and both were packed off to England for schooling, where, to relieve loneliness and unhappiness, they turned to reading. Another book Orwell read in childhood, Gulliver’s Travels, remained a more conscious presence in his literary imagination — it was a book to which he returned regularly. But, in another way, Kipling too was a part of his literary background.

Orwell’s chief question regarding Kipling’s verse is why it has survived. It is not because of its quality, but because of something Orwell does not recognize: the power of rote recitation. Since Orwell’s death in 1950, there have been many changes in education, and notably the decline of “poetry appreciation” by assigned memorization. And even if recitation is part of the school curriculum, I doubt it includes Kipling. Orwell (in 1942) is addressing a readership for whom Kipling’s verse is a permanent resident in memory. I have saved myself a good deal of grumbling by avoiding Kipling’s verse; there were several “poetic revolutions” in the course of Kipling’s lifetime which had no affect upon him: his verse is fundamentally old-fashioned. This is not a question of rhyme, but rather the combination of a rhyme scheme to the beat of a metronome. Furthermore, popular poetry in the Victorian era simply sought different effects, and Kipling (1865 – 1936) was always a Victorian poet. Compare Kipling’s poems to those of his contemporary, W.B. Yeats (1865 – 1939) and Kipling’s rather stubborn adherence to outmoded poetic purposes is apparent. Orwell often said that Yeats was among his favourite contemporary poets, and as it seems unlikely that Yeats would have been assigned reading at Eton, this reflects Orwell’s personal choice. Orwell considered both of them to be “reactionary.”

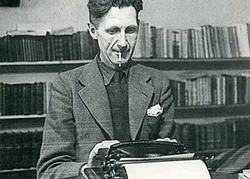

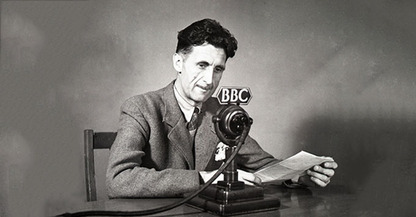

Orwell has the distinction of writing some of the most enduring political literature of the XX century. His greatness consists in his steady independence; I think he was aware that “political literature” is too often an oxymoron: his dissatisfaction with the “party line” is evident throughout his writing, but especially after 1937 (The Road to Wigan Pier). Indeed, I dare apply to him the oxymoron he coined to describe Jonathan Swift: a Tory Anarchist. I am confident that many will bristle at the term’s reference to Orwell, but the value of an oxymoron is that the friction between its parts can set off illuminating sparks.

Had Orwell chosen to look at Kipling’s stories, I think he would have made more of Kipling’s outsider position. Kipling had been born into a world where the British Empire seemed not only inevitable but permanent. Though the Empire was the basis of his career, he was not officially part of it; he was a newspaper man. Kipling’s verse tends to be a bit monocular, insofar as he seeks to make a single (moralistic) point. But, taking an obvious example, a short story such as ‘The Man Who Would Be King’ is an adventure story with strong undertones of being a history of Imperialism in miniature — even including what must have been unimaginable to Kipling: its collapse. The story undermines the certainty with which Orwell declares: “. . . Kipling does not seem to realize . . . that an empire is primarily a money-making concern . . .” The first direct statement from Peachy contradicts this: “If India was filled with men like you and me . . . it isn’t seventy millions of revenue the land would be paying – it’s seven hundred millions.” Had Orwell written of

Kipling’s fiction, we would have been spared his curious error in describing The Light that Failed as Kipling’s “solitary novel.” Kim can also be seen as an adventure tale, but its Eurasian hero (like Kipling, like Orwell) is caught between two worlds. The Eton-educated Orwell spent five years in Burma as a member of the colonial police; he was therefore an officer of the Empire, responsible for enforcing the power of Britain. Let’s say that the money was good, but the ethics bad. Orwell would not have such |

financial security again until he entered the India Office for English propaganda in World War Two. If Orwell noticed the irony, he does not seem to have mentioned it.

I think Orwell is determined to be fair to Kipling, particularly to counter the common left-wing response that Kipling was somehow fascist. (Kipling’s use of the Hindu good luck sign, the swastika, makes this an easy assumption.) He describes Kipling as having “some streak in him that may have been partly neurotic [which] led him to prefer the active man to the sensitive man.” This could easily be turned upon Orwell himself. From early childhood, Orwell had suffered from weak lungs: a final haemorrhage in January 1950, and he was dead aged only 46 years. This did not prevent him from living as a tramp or sharing the experience of coal miners or joining a military brigade to fight in Spain. Great books were the result, but not exactly the work one might expect from an Eton boy. As a stranger at home, Kipling seriously considered living permanently in the United States, but circumstances drove him back to England; thereupon, it seems, he dedicated himself to become the model Britishman (as a Catholic convert is often more doctrinaire). Orwell always had the upperclass speech that Eton gave him, which (besides his high-brow literary taste: alongside Yeats, Joyce was another contemporary Orwell praised) set him apart from the tramps and workers and militiamen of whom he wrote. Citing “several private sources,” Orwell reports that the Anglo-Indian establishment did not much care for Kipling: “. . . he was from their point of view too much of a highbrow.” This charge was also brought against Orwell from his left wing associates; even today, the splintered left seems to unite in what Orwell called the “hunting of the highbrow.” Orwell could praise the writing of those he considered “reactionary,” demonstrating an ability to discern a difference between literature and politics. There are characteristics of Orwell with which we may disagree or even find repulsive, but they do not undermine the integrity of the whole (if anything, they add the shades required to make human “Saint Orwell” — a title which I believe would have disgusted him).

To clarify the “irony” I have suggested: we have here a man engaged in producing propaganda writing an essay on a man who is roundly condemned for writing propaganda. It is well known that Orwell’s experience at the BBC greatly informs the opening portion of 1984. Orwell’s contribution to the war effort is nowhere as heavy-handed as what is customarily called propaganda. Besides his commentaries about the military action in Asia, he wrote radio plays (one from a Hans Andersen story), offered remarks on Swift and Macbeth and Oscar Wilde, and arranged poetry programs that included T.S. Eliot. The most important issue underlying his Indian broadcasts was to keep the Indian left from joining up with the advancing Japanese forces: a tricky issue for Orwell, who supported Indian independence, but who also suspected that India would be no better off under Japanese domination than British. But the efforts were moot: of a population of 300 millions, only 100,000 Indians actually had radios (a potential audience of .04%!) and the number who actually listened is incalculably smaller. Kipling, on the other hand, in 1903, was perhaps the most widely read author in the English speaking world.

Kipling’s work was made easier by the fact that most of his readers were inclined to agree with him. A final irony. Orwell wrote: “Kipling is the only English writer of our time who has added phrases to the language.” Until Orwell. |

|

As I Please: Simon Loekle |

|