|

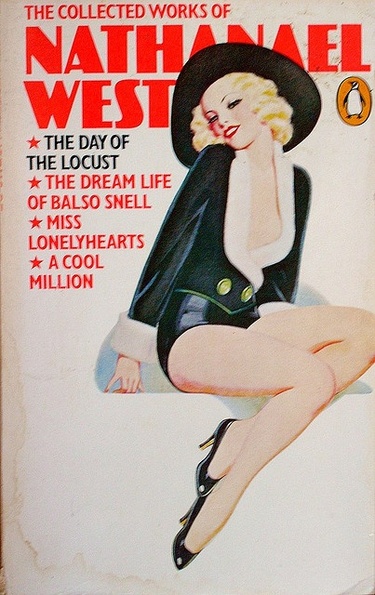

A COOL MILLION: the dismantling of Lemuel Pitkin Nathanael West Nathanael West was born Nathan Weinstein in New York City, 17 October 1903. He was the son of Max and Anna Weinstein, wealthy German-speaking Jews who had fled Europe to escape persecution. Max was in the construction business (he had in fact married the boss's daughter), initially his career in New York was building tenement houses on the Lower East Side, but as the business prospered, Weinstein turned to more luxurious projects. After Max and Anna married, in 1902, they moved to one of his houses at 151 East 81st Street. Subsequently, the family would move to newer and better buildings built by Weinstein's company. Like his slightly younger contemporary, George Oppenheimer, Nathan Weinstein is a representative of the urban upper class Jewish experience in the early XX century: summers at the seaside or among the mountains, brought up to appreciate intellectual pursuits, encouraged to consider an Ivy League college as a fitting destination, offered any number of brilliant careers to chose from, such as law, or finance, or medicine, or even taking control of the family business. Yes, both the young Nathanael West and young George Oppen were raised to see the world as their oyster. Neither chose to swallow it; it wasn't kosher.

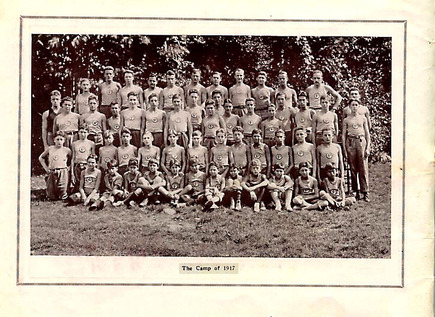

As a boy, West displayed a great hunger for hi-brow literature and a great enthusiasm for outdoor life, an excellent combination. In 1917, he spent his first summer at Camp Paradox, in the southern Adirondacks; there he received his lifelong nickname "Pep" which was bestowed upon him by his chums after a hike up Mount Marcy: the exhausted lad slept all the next day. The glorious wilderness of the Adirondacks offered "Pep" a fundamental American experience: the confrontation of the frontier.

His keen understanding of the nature of America displayed itself in a few fraudulent acts. A mediocre student, he dropped out of DeWitt Clinton high school; in order to pursue a higher education, he forged his school transcript, adding the necessary credits. The ploy worked; in 1921 he entered Tufts University, where he dallied for a semester, barely sullying a textbook. Was Tufts too tough for Pep? He got his hands on the school records of another Nathan Weinstein, and used these to enter Brown University as a sophomore. (Here he met his lifelong friend and future brother-in-law, S J Perelman.) It is 1922: he remains a lazy student, but he is prepared to cast his lot with the literary revolution; his participation in the sexual revolution of the roaring twenties got him a case of the clap; thereafter, the disease would occasionally flare up, causing periods of intense and immobilizing pain.

|

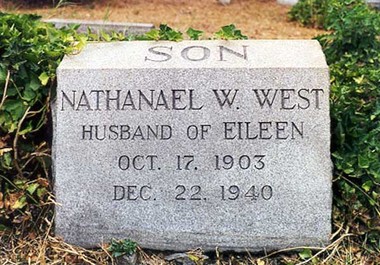

In 1926, he legally assumed the name Nathanael West, and (thanks to the financial support of two uncles) visited Paris for the first time; even though, since high school, he had dabbled in poems and prose and illustrations, this is when his career as a writer starts. He began work on his first novel, The Dream Life of Balso Snell, which bounds along with youthful satiric exuberance. This portion of his life is fairly well rehearsed: plugging away at the four novels, his night jobs at New York City hotels, the Hollywood years, the determined ignorance of reviewers and readers (in 1934, West estimated that the royalties for his first three novels fell just shy of $800). It is a familiar story (alas: one thinks of Keats). It should be firmly stated, however, that if the public was largely unaware of Nathanael West, American writers were not. S J Perelman introduced him to the New Yorker staff (Thurber, Parker, Woolcott and Kaufmann); he had close friendships with Dashiell Hammett and William Carlos Williams, went hunting with William Faulkner; Scott Fitzgerald, another on the Hollywood outcast couch, visited West just days before he (Scott) died. Heading back to Hollywood from a weekend's hunting in Mexico to attend Fitzgerald's funeral, West and his wife died in a car accident, 22 December 1940.

West is buried in Mount Zion Cemetery, Maspeth, Queens. Screen Credit

Writers who cherished notions of freedom of expression and artistic integrity were at once at odds with the Hollywood silverscreen machine, which offered not easy money, but steady money. The garret was replaced by almost factory-like conditions: the writer was expected to turn up five or six days a week at the office provided by the studio, put in an eight hour day and produce pages. Sometimes the job meant revising or "doctoring" another writer's script; sometimes, after weeks of work, the project was abandoned. The patience of the novelist or playwright, who might work on something over the course of months or years, was seen as a disadvantage in Hollywood, where the only sin greater than going over schedule was going over budget. In the end, the writer who may have had no greater connection to his script than the weekly paycheck, found his reward in the three seconds of fame known as the screen credit. William Faulkner worked on over two dozen filmscripts during his time in Hollywood, he received screen credit for only four. West fared better, so far as screen credits go, even receiving solo credit for three or four films, but chafed just as much as Faulkner at the limitations Hollywood imposed upon material and method. Though West had worked in Hollywood in 1932, his real work began in January 1936, when he showed up for work at Republic pictures, for a salary of $200 per week. Over the next four years, he would receive screen credit for about twenty movies. If income is the American measure of success, Hollywood was good for him: in 1940, he and his writing partner, Boris Ingster, sold two treatments for a total of $35,000. I can't help thinking, however, that West considered himself first and foremost a novelist, and that he was only working in Hollywood to make a cool million.

The Text

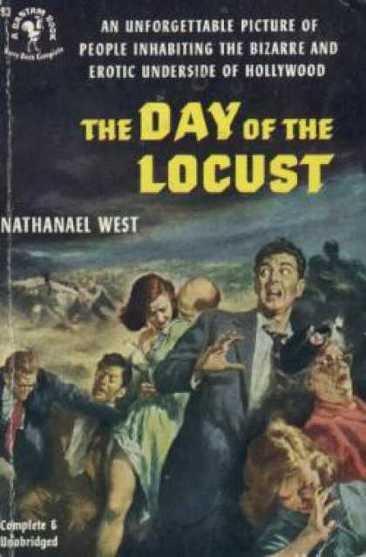

Published in 1934, A Cool Million is a cold-blooded satire and a brutal parody of the Horatio Alger story. The novel came quickly to him; he began work around the time of the publication of Miss Lonelyhearts (April 1933) and he received his first rejection slip in November. Eighty years later, the book still has the power to shock and dismay its readers, readers who accept blandly Swift's humble cannibalism, readers who barely blink when Haze Motes blinds himself. Its mirthless irony stands in such sharp contrast to the general tone of American literature of the time, small wonder it received poor reviews and made no mark on the best seller lists. Horatio Alger is a fine example of the "Gee-whiz School" of American Literature (far from extinct!), which takes literally Oscar Wilde's quip "The good end happily, the bad unhappily: that is what fiction means." For Alger, hard work was not enough to secure a happy ending, typically there is a stroke of good fortune which puts the hero under the protection of a wealthy patron. But the formula "from rags to riches" was not only appealing fiction, it could be seen in the life story of notable Americans, like Andrew Carnegie, J.D. Rockefeller, even Mark Twain. Americans are quite earnest in their preference for the superficial. The wealth and glamour of Gatsby's world obscures its Algerian ironies: the self-made man is a criminal. Hence the crucial importance of the subtitle. |

|

"Sweet are the uses of adversity."

Conflict, they'll tell you in Writing 101, is the essence of narrative. Plot, or the momentum of the tale, demands it; it displays character; it offers variety as well as specifics. The travels of Odysseus, the troubles of Oliver Twist (each, in its way a story about Home) present triumph over adversity; other protagonists are not so fortunate. The uses of adversity are nowhere more evident than in the daily Soap Opera, yet even the most extravagant fictions of Soap Opera are tearlessly mild next to the misfortunes of Lemuel Pitkin, who bears the scars of his dismantling.

Lem remains, almost stubbornly, the Innocent Victim throughout. The "Innocent Abroad" as a satiric format has long and good standing (Pitkin's namesake, Gulliver; Twain's Huck Finn): but I don't think any Innocent is as roughly handled as Lem Pitkin. Through the course of the novel, only Shagpoke Whipple undergoes a change in outlook. Besides Mrs Pitkin; Betty Prail (the other Innocent); and Chief Jake, who alone among the people Lem meets tries to help him, the other people we meet are, for once and all, cheats and charlatans and bullies. By 1934, grumbling about Wall Street fraud was almost a national pastime, but it dates back to before the War Between the States. ("Bartleby" was published with the subtitle "a story of Wall Street," and even then [1853] it would have been possible to find ironic comedy in a Wall Street lawyer trying to do the right thing; one of the Snopes children was named Wall Street Panic Snopes.) But the confidence trickster was an established figure in the American scene: cheating was as American (and simple) as apple pie. The spirit of fraud is emblazoned in the nickname for Connecticut ("the Nutmeg State") recalling the Yankee |

Ingenuity of the Connecticut salesman who made a fortune selling false nutmegs, in reality mere bits of wood. At the St Louis exhibition of 1904, an enterprising merchant saw his chance to sell wooden nutmegs at a nickel a piece. When he ran out of wooden nutmegs, he sold real ones, without informing the public, and still made a profit at a nickel a piece.

West's fortunate foray into fraud and forgery, which provided him college experience (he did not display much interest in a college education), can be seen, in retrospect, as displaying his early comprehension of the nature of American ethics. The story of his fixing up his transcripts to get ahead is often cited, but I am not satisfied it is entirely true: it is exactly the kind of story West loved to tell about himself, which often turned upon his laziness and physical incompetence. Nevertheless, it holds great thematic importance for his fiction.

|

|

A Museum of American Horrors.

Marginalia

[1] The situation with which A Cool Million opens, a widow threatened with eviction, is familiar to all, chiefly through parody. I can not say for certain that I have ever seen the device "legitimately" employed, and though I dimly recall a silent screen scene presenting the gist of it, by that time (I may have been ten) melodrama had been undermined by comedy. Lawyer Slemp assumes some of the bestial qualities of the melodramatic villain, but Squire Joshua Bird is moved to evict because of idle greed. Lem will be tossed between the greedy and the bully for the rest of the novel. [2] Strong arm methods are employed in force: by the police, the riot squad of International conspiracy, or agents of Wu Fong (a most successful businessman). There is also an Indian attack. You will notice such brutality proves successful. [3] Fraud, or The Phoney —: hat tip to Holden Caulfield, who might be usefully compared to any Algerian hero. |

[4] The confidence man has a special place in American literature (the term itself is American-born): there's Herman Melville's novel, the King and the Duke of Huckleberry Finn, the comic persona of W. C. Fields, the travelling salesman, Elmer Gantry, the shady enterprises of Hope and Crosby in the Road pictures. The first criminal Lem encounters, Mr Wellington Mape, a pickpocket, practices what might be called the most intimate form of theft, but it is the meticulous presentation of the Glim Drop that is most arresting. [5] The care West lavishes on the interiors and costumes of Wu Fong's All American Whorehouse (notably inspired by a Hearst campaign to "buy American") shows that style can cover a multitude of sins. The pursuit of the quaint initiates Lem's dismantling; the collection of kitsch in the Museum of American Horrors: another perspective on the "fashions" of A Cool Million. [6] One element of Chief Israel Satinpenny's tirade against the paleface turns upon almost legendary Yankee Ingenuity, here displayed in production of kitsch: "clever cigarette lighters . . . superb fountain pens . . . leatherette satchels . . . " The word "kitsch" (defined by the OED as objects "characterized by worthless pretentiousness") was not yet entirely incorporated into English, but the concept was familiar. There is kitsch in the interior decorations of Wu Fong's houses, and in the purchase of the Pitkin homestead so that it may be placed on display in a Fifth Avenue shop window. Satinpenny's complaint is closer to the original German sense, "trash;" the word has gathered a measure of "liberal tolerance" over time; today, Keane-eyed paintings summon a smile rather than a fire-axe. Horatio Alger is a literary manifestation of kitsch, and though an object of scorn and derisive laughter even before his death in 1899, there lingers a pernicious influence for those who read without care, without taste, without critical acumen: Alger reduces the expectations a reader might bring to the project of reading a novel. Alger is only a symptom: if the basic Algerian plotline is now outmoded, the simpleminded novel is far from extinct, and mainstream, mindless, sentimental entertainment has been gussied up considerably with sex and violence. A Cool Million unfolds blandly, matter-of-factly (a technique West might have honed with Hammett): hard-boiled Alger. The absence of sentimentality curiously makes Lem more memorable than any of the interchangeable Algerian heroes. |