|

NOTES ON THE SERMON

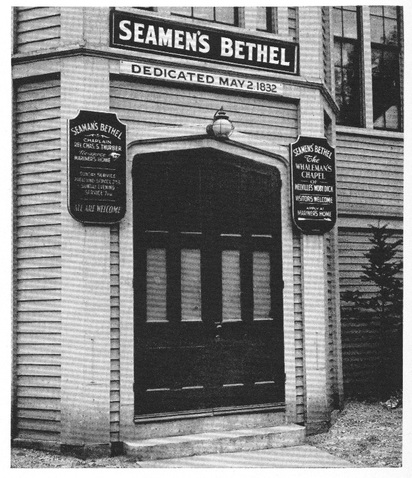

Until the close of the XIX century, when technology allowed bigger and faster runs, the publication of sermons provided steady work for printshops: ephemera on the topic of eternity! Donne's sermons at St Paul's remain readily available today, included in standard editions of the Poems, and the praise of T.S. Eliot revived interest in the sermons of Lancelot Andrewes: these two cases indicate that the sermon's primary value is now of greater literary concern than theological. Early in the XIX century a volume of the complete works of Jonathan Swift consisted of his sermons, but good luck finding them today, except for such on-line sources of out-of-copyright books as the Gutenberg Project. Pamphlets and broadsides quickly suffer the ravages of time: handled, folded, bent, spindled, and otherwise mutilated; no doubt there are surviving examples to be found in the back rooms and dusty corners of the older libraries round the world, but one must frankly ask, who would be interested in perusing the religious oratory of a XVII century priest? James Joyce, for one. The Sermons that make up the bulk of the third chapter of the Portrait closely follow the text of an Italian Jesuit, Giovanni Pinamonti: Hell Opened to Christians, first published in 1688, and translated and published in Dublin (anonymously) in 1868. According to the best chronology we can establish regarding Joyce's novel, the sermons were delivered in 1896: it is an essential albeit invisible irony that the Christian conceptions here presented are over 200 years old. There are two possible "originals" for Father Mapple in Moby-Dick: Fathers Edward Taylor and Enoch Mudge. Taylor preached at the Seaman's Bethel in Boston; Father Mudge held forth in the Whaleman's Chapel in New Bedford. None of my sources refer to any published sermons by either, but Taylor had a wide reputation in his time, and it is more than likely that Melville attended services by both (preaching was a kind of popular entertainment at the time). |

Mapple's sermon seems a fair indication of the style of the age, and besides its obvious importance within the novel, offers clues to understanding the broad lines of Walt Whitman. These historical considerations pale next to the glories of the Sermon itself: the grandest, most glorious sermon to be encountered within a novel because, besides its dramatic irony in context (it's a whale of a tale), it does what a sermon ought to do: offer courage, backbone, a notion of individual worth, a sense of pride and joy in being human by doing what is Right and not what is merely expedient convenience. The Sermons of the Portrait are well-crafted and spectacular: but their aim is to make us cringe and bow before a powerful deity. The Sermon of Moby-Dick recognizes that power of God, but gives us the opportunity to stand upright for Justice. (William Blake said that he had little respect for a God who demands us to kneel before him.) The bitter irony of the Joyce sermons is that we should not be persuaded by them. The glory, the high reaching and overarching glory of Melville's: this is how we ought to live. The rising cadences of Melville's prose, the easy vernacular of the opening (Jonah, "with slouched hat and guilty eye") to its triumphant end ("and destroys all sin though he pluck it out from under the robes of Senators and Judges") — this is why the Sermon is the best of all, why even Joyce is a distant second. Melville's Mapple condenses all of Thoreau, and far exceeds the lip service of Whitman, who too often revised his work to gain a better reputation. Of course, in these United States, we hear much talk about independence, then crush the independent among us. Stand up, and stand still: Melville's the Man: read him.

|

|

The Day Job

In December 1866, at the age of 47, Herman Melville took his oath of office as Inspector 75 of the Port of New York, and so ended his career as a working writer. He continued to write, now poems, some of which he collected in small privately printed editions; he would not return to prose until he retired from the Customs Office in 1885. By that point, his greatest fame was over 30 years behind him. There would not have been the Melville Revival of the 1920s if there hadn't been a period of Melville Obscurity. The position in the Port of New York was, for Melville, a job that would pay the bills: a regular salary, which he had never been able to count upon as a working writer. It is difficult to determine his daily duties; he rarely mentioned it, but typical of this kind of bureaucratic appointment, it seems the primary requirement was showing up. Not always awarded on merit, the civil service sinecure has a long (and troubled) tradition in the arts: Wordsworth drew a salary as a postmaster; Hawthorne's assignment to the U.S. Consulate in Liverpool was a reward for having written the campaign biography of Franklin Pierce. (The role of bureaucracy in Chinese poetry is another topic altogether, mentioned here as a kind of rhyme.) With a regular salary (paid monthly at the initial rate of $4.00 per day) Melville must have felt some relief, which was mingled with a measure of boredom associated with paper-pushing duties. Occasionally, it seems, he was required to visit a ship to carry out his inspection, but I do not believe this to have been a regular function of the job; rather, I imagine he was more commonly deskbound, armed with stamps and seals and red tape. On his first day, he reported to District Office 4, at 207 West Street (at Harrison Street). Until the mid 1970s, this was still the Spice District. Today some call it TriBeCa.

In 1869, Melville moved to a new office, still along the waterfront, at 470 West Street, what is today the WestBeth Artist Apartments. WestBeth occupies the site and some of the buildings of the old Bell Laboratories which, at the close of the XIX century, had replaced the buildings Melville had known. Melville's time in New York City seems especially plagued by such "phantom addresses"; when Melville and family returned to New York City from Pittsfield Massachusetts in 1863, they set up house at 104 East 26 Street (also a victim of demolition long ago). Still, 470 West Street is the location perhaps best identified with

|

Melville's day job: Inspector 75 would leave his home each morning and walk to work, about an hour's worth of exercise and solitude, and en route to the west side waterfront, he would regularly cross Gansevoort Street (named in honour of Melville's grandfather): 470 West Street was two blocks south of Gansevoort. One of the few references Melville made to the Customs office is found in a letter to his mother (5 May 1870):

The other day I visited out of curiosity the Gansevoort Hotel, corner of "Little twelfth Street" and West Street. I bought a paper of tobacco by way of introducing myself: Then I said to the person who served me: "Can you tell me what this word 'Gansevoort' means? is it the name of a man? and if so, who was this Gansevoort?" Thereupon a solemn gentleman at a remote table spoke up: "Sir," said he, putting down his newspaper, "this hotel and the street of the same name are called after a very rich family who in old times owned a great deal of property hereabouts." The dense ignorance of this solemn gentleman,--his knowing nothing of the hero of Fort Stanwix, aroused such indignation in my breast, that disdaining to enlighten his benighted soul, I left the place without further colloquy. Repairing to the philosophic privacy of the District Office, I then moralized upon the instability of human glory and the evanescence of — many other things. Another rare reference to his office occurred in a letter to his uncle, Peter Gansevoort in December 1871:

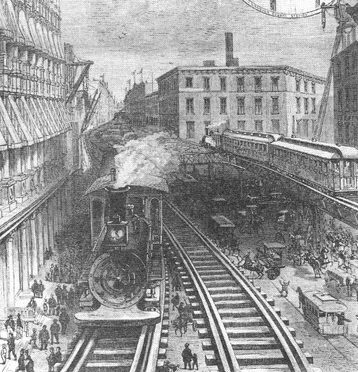

I write this at my office, so you must excuse the paper; it is the best I happen to have at hand here. Melville had not abandoned literature, just the literary marketplace. Freed from the contractual and financial obligations to produce book after book, Melville worked on the long poem Clarel, which finally appeared in 1876, printing costs (about $1200) paid for by Peter Gansevoort. That year, Melville's office moved two blocks north to 507 West Street. In the spring of 1877, a push to purge the Customs Department of featherbedding lazeabout political appointees almost cost Melville his job; in the end, he survived the cuts but found his hours increased. (And what might a "day" in the office entail? For example, what was his report time?) After the shakeup and consolidation of the Customs Department, Melville's office was listed in the Directory of 1878 as 6 State Street, but it appears that at this time, he reported to an office far uptown, at 76 Street and the East River (where Avenue B resumed its course). There was a bridge to Blackwell's Island there, and imagining Melville's office window overlooking the East River, he'd have had a view of the smallpox hospital. The Third Avenue El began its run in 1878 — there was a station at 76 Street. I like to think Melville still walked to work, but perhaps he got the El back home. On 31 December 1885, Melville handed in his letter of resignation, bringing this astonishingly mysterious chapter of his life to a close.

--Simon Loekle

|