Homerphiliai. INTEGRITY Though the works of Homer are very old, they have been remarkably well-preserved — especially if you consider the fragmented state of Sappho, or the lost plays of Sophocles. The two great poems were perhaps written down three thousand years ago, this after generations (many generations) of oral performance; Sophocles would have considered Homer ancient. So there is the integrity of the text, which we have received in far better condition than many plays by Shakespeare or even the Ulysses of James Joyce. But there is also the integrity of the poem, the wholeness or thoroughness with which it was conceived. Religion, too, is integral to the story, the sacrifices and supplications, the many occasions when a god appears (at any time and in any form) to shape the ways of mankind. The sacred is never far to find in Homer, but just as regularly we find details of attire and weaponry and strategy: all of this serves the fundamental humanity of the whole: the integrity of character. ii. The People We Meet

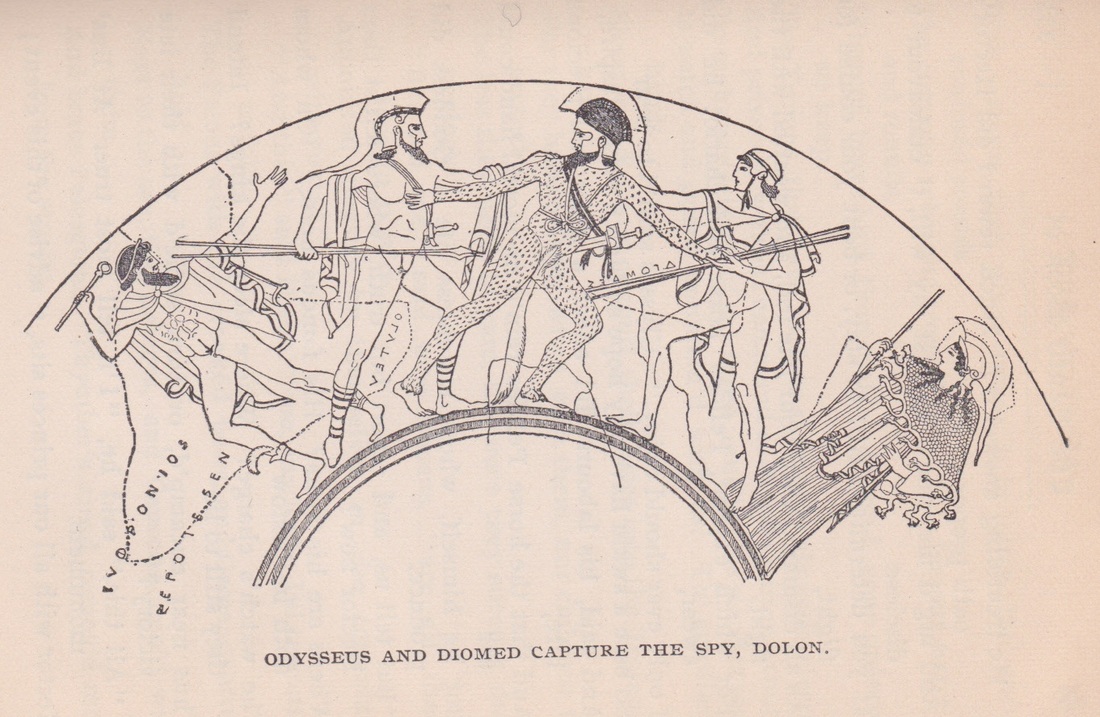

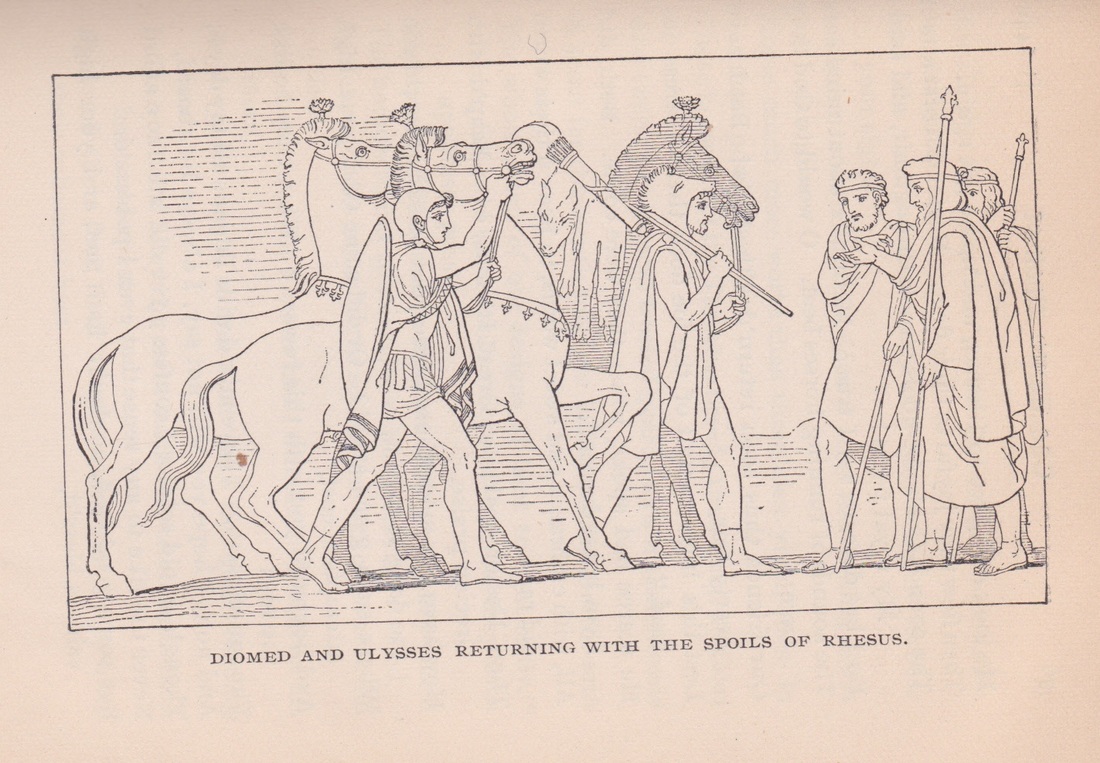

Iliad, Book X, (Night Action).

(unless otherwise stated, quotations from Robert Fitzgerald) The story so far? The Greeks have suffered a severe defeat and have been beaten back to the shore. Night falls, and the Trojans retire. Some hours later, we are brought to Agamemnon's tent, where we are presented with a familiar scene: the troubled sleep of the monarch. There's nothing new in saying that Homer, throughout the Iliad, cannot be accused of flattering the Greek invaders. Within the Iliad, we will see Agamemnon reveal his more boarish characteristics, and we know his past, and his (limited) future. His stubborn greed created the primary situation around which the Iliad revolves: the sullen anger of Akhilleus; still, though the wee hours of the morning, Agamemnon is shown in a good light. Our knowledge of the span of Agamemnon's career is not the advantage of a XXI century perspective: it was known to the first respondents, so that the slightest phrase might evoke "the rest of the story." The underlying tragedy of the Iliad is not simply the protracted and pointless war, nor the sulking Akhilleus, but also an end of an era. This is the end of the age of Heroes, and the Odyssey is the last stand of the hero.

We are frequently reminded that Menalaos has red hair, the full significance of which may be difficult to recapture yet it seems much more than a descriptive note. A number of unflattering characteristics are attributed to redheads: unlicensed sexuality, treachery (Judas), hot temper. Pound suggested that it was seen as an invitation to be cuckolded (Letters, #294). On his behalf, the Akhaian army travelled across the sea and fought the Trojans (the war lasted something like 4000 days; the Iliad covers about 40); he is among the few to return safely home. |

Nestor is a figure of continuity, active throughout the three generations of the Heroic Age. His eleven brothers were slaughtered by Heracles, he fought side by side with Jason, he knew Autolycus, the grandfather of Odysseus. With age there is wisdom, and he is shown all due respect, though there is an underlying comic potential to become a bit of a Polonius, a garrulous elder statesman. Fitzgerald captures this slyly, just before Diomedes and Odysseus return to the camp: He had not yet finished all he was going to say…

The presence of a past that interlinks the characters, our sure knowledge of each one's fate (though in the case of Odysseus, I grant the last word to Dante) gravely informs the Iliad: they do not come out of nowhere. A ready example concerns the helmet Odysseus borrows before he and Diomedes set off on their nighttime scouting mission. I quote from Chapman's Homer, as sign of Homer's presence in our past:

. . . His helmet fashion'd of a hide; the workman did bestow

Much labour in it, quilting it with bow-strings, and without With snowy tusks of white-mouth'd boars 't was arméd round about Right cunningly, and in the midst an arming cap was plac'd, That with the fix'd ends of the tusks his head might not be ras'd. This, long since, by Autolycus was brought from Eleon, When he laid waste Amyntor's house, that was Ormenus' son. In Scandia, to Cytherius, surnam'd Amphidamas, Autolycus did give this helm; he, when he feasted was By honour'd Molus, gave it him, as present of a guest; Molus to his son Merion did make it his bequest. With this Ulysses arm'd his head . . . Odysseus dons his grandfather's headpiece. Here, in an aside that might escape notice, we see the etiquette of hospitality ("as present of a guest") the violation of which by Paris led to ten years war.

This scene takes place in the chilly hours before dawn. We are informed how each of our heroes dresses: Agamemnon throws a lionskin ("dangling to his heels") around his shoulders, Menalaos wears a leopardskin. Nestor's red mantle is lined with fleece. Diomedes also chooses a lionskin for a cloak; Odysseus, however, only picks "a painted shield to hang from his broad shoulders." I do not think this is Homer's carelessness but a character detail. Odysseus is nothing if not cool. --Simon Loekle

|

|

As I Please: Simon Loekle |

|