|

In the American Grain by William Carlos Williams is an important and indispensible collection of essays exploring American history as seen by a major modernist poet. Published in 1925, the one literary figure discussed is Edgar Allan Poe, long a darling of American intellectuals. Poe is not much concerned with local colour, his Americanism is almost defined by his un-Americanism: the crime and decadence of the Old World is a recurring theme; the horrifying and the grotesque that lies beneath the surface of civilization. In 1925, Melville was just emerging from a long period of obscurity; Moby Dick is informed by his global perspective: it becomes more and more American with each passing year. In 1925, Mark Twain had been dead for only 15 years, but the true value of humorists is often overlooked. Neither Ezra Pound nor Williams make any mention of Twain that I have found, though it is arguable that Twain helped shape the "Cracker-barrel vernacular" that marks Pound's correspondence. Eliot praised Twain, and I believe this is more than just loyalty to a fellow Missourian. Ernest Hemingway is famous for his statement that "all American literature descends from Huckleberry Finn" (snubbing Hawthorne, Melville and Poe!) but Hemingway himself shows no Twain influence. Papa is rarely funny, and rather dull, and I suspect that his praise for Twain was cribbed from some other source, perhaps Eliot, or Fitzgerald, or even Mencken. As scholars mined the mountain of manuscripts Twain left behind, his reputation has steadily grown; today, only an idiot would deny Twain's place among the greatest of American writers.

On the American Twain

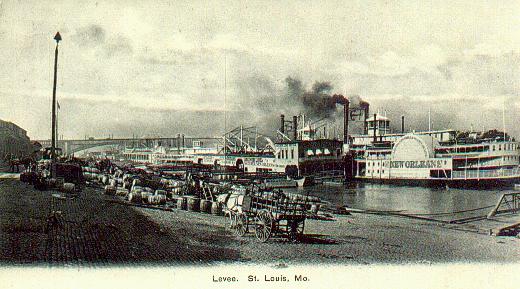

Perhaps the most American, geographically at least. He embodied American mobility, first as a journeyman printer. Between 1853 (when he was 18 years old) and 1857, the young man headed, not for the wilderness like Daniel Boone, but to the growing cities of the north, like New York, Philadelphia and Cincinnati — as though there was no work to be had in Richmond, Charleston or New Orleans. It is easy to overlook that at this time Hannibal was Missouri's third largest city. Its development depended not on agrarian slave labour, but the mechanical innovation of the railroad and western migration. |

Pursuing Northern career opportunities raises the question if young Mr Clemens ever seriously identified himself as a Southerner, despite five years as a pilot on the transportation system that seems primarily associated with the South, the Mississippi river boat. Rather than confirming a Southern identity, he was a professional outsider, just passing through. Indeed, he was in a prime place to notice the differences within the South, not the least being the distinctive dialects from place to place, which earned an explanatory note at the top of Huckleberry Finn: “In this book a number of dialects are used . . . The shadings have not been done in a haphazard fashion, or by guess-work; but pains-takingly, and with the trustworthy guidance and support of personal familiarity with these several forms of speech.” Considering Missouri as a Southern state might be moot, as Missouri did not secede from the Union, were it not for the fact that it had a place as a star on the rebel flag. Clemens was briefly part of the Confederate Army, it took him no longer than a week to determine that the military life was not for him, but even this barely qualifies him as a Southerner, other than as evidence that he harboured some of the romantic notions that would later be attached to Tom Sawyer. (If the primary political cause for the war was the issue of slavery, Clemens might be introduced as an example of how little the average soldier - the grunt, in modern parlance - thought about it. Certainly, he did not enlist to fight in defence of slavery, and as soon as he discovered that war was not as glamorous as he had imagined, he lost no time in lighting out for Western territories.)

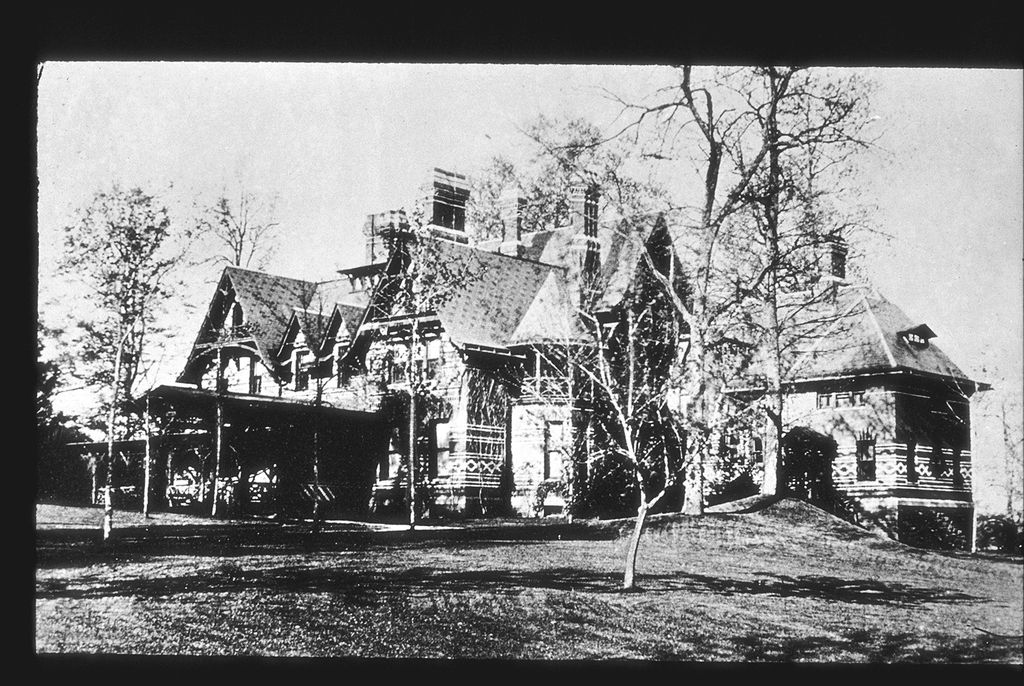

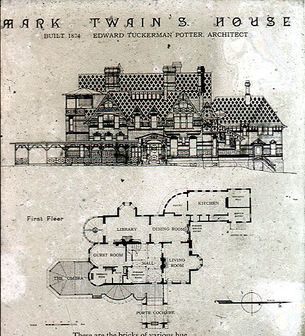

Out West, he secured his identity with the pseudonym Mark Twain, and achieved his initial national fame as a representative of Western writing. Out West, too, he began his career as a public performer, and, in his stage persona, there were some Southern elements, if you will allow a slow and drawling speech to be “Southern style.” I tend to believe that his continental perspective would have given him a special freedom from regionalism, that he would have spoken differently at Oxford from how he spoke at home in Hartford. This is, alas, speculation, but it makes a kind of sense. In 1866, he reversed the course of the Gold Rush and headed East to make his fortune. Another American mobility: class mobility, rising from the poverty of his childhood in Hannibal to become perhaps the wealthiest writer in the United States through bankruptcy to success again. The marvellous mansion in Hartford Connecticut is as good an example of the Gilded Age as any, but deserves special mention since Twain coined the term. |

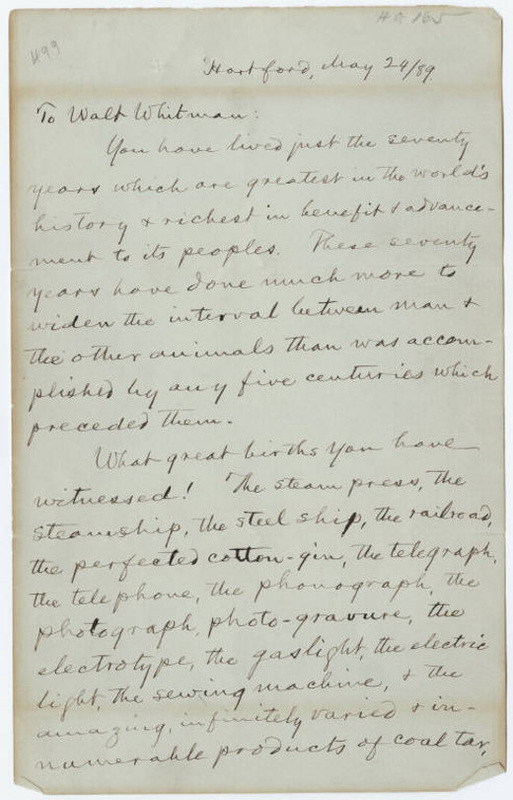

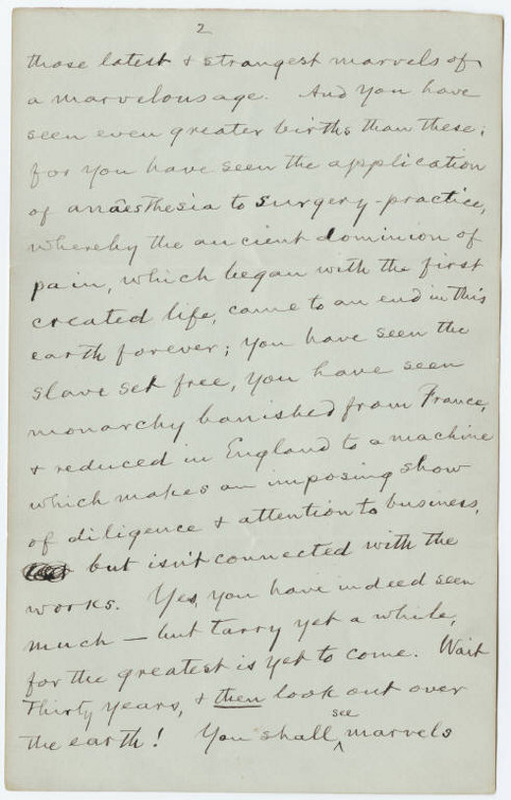

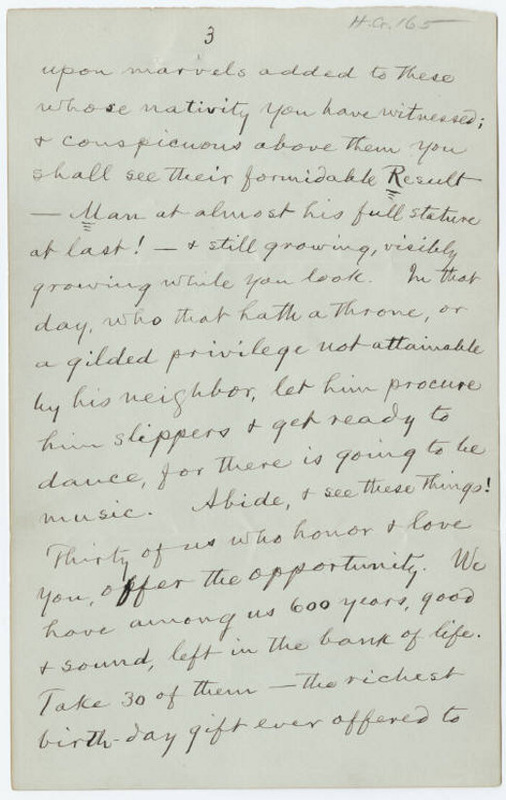

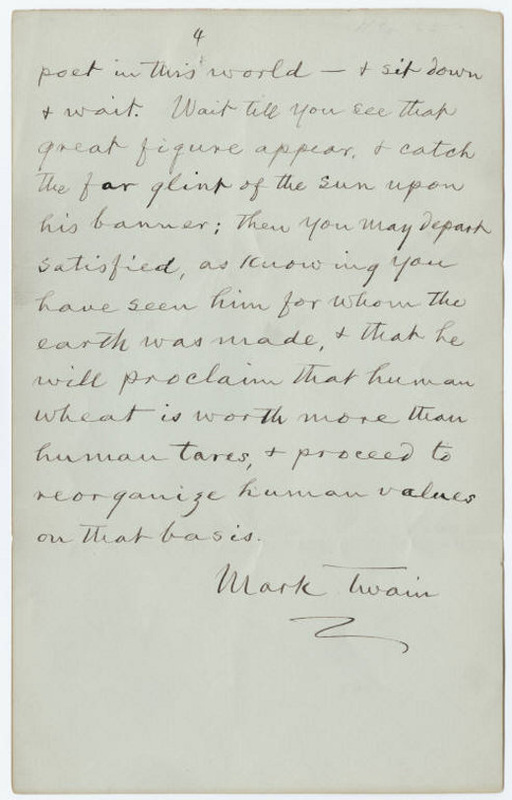

Mark Twain wrote this letter to Walt Whitman on the occasion of the poet's 70th birthday (1889). Twain, one of the most financially successful writers of the day, had previously made generous contributions to a number of campaigns to support Whitman, whose health was in decline and who had no appreciable income. It is the apex of all American optimism on Twain's part — in the next year, Paige's typesetter brought Twain to bankruptcy: he left his Hartford mansion, resettling in Europe, where over the next ten years, he worked to repay his debts, dollar for dollar. Upon his return to the United States, he was greeted as a hero, but henceforth a Dark Twain dominated the writings. This darkness runs throughout his work, you can find it cropping up in Connecticut Yankee, it informs Huckleberry Finn. It is not the result of personal bitterness but personal liberation. Damn the consequences: free speech ahead.

|

NOTES

Twain composed Was the World Made for Man? in 1903, in response to a series of articles in the Literary Digest that had stirred up interest in Creationism, a theory which seeks to accommodate the principles of evolution with the Abrahamic account of genesis: in effect, God's master plan in slow motion. The essay was not published in his lifetime, and, as best as I can determine, it was first published by Bernard DeVoto in 1962, in the collection Letters from the Earth. At the head of the manuscript are two "clippings" representing the source of his inspiration. Alfred Russell Wallace's revival of the theory that this earth is at the centre of the stellar universe, and is the only habitable globe, has aroused great interest in the world. Literary Digest |

For ourselves we do thoroughly believe that man, as he lives just here on this tiny earth, is in essence and possibilities the most sublime existence in all the range of non-divine being — the chief love and delight of God.

Chicago "Interior" A.R. Wallace (1823 - 1913) was a well-known scientist of the day. A bit younger than Darwin, he was an evolutionist, an ecologist and, at the end of his career, a Creationist advocate. ● Twain's final years were almost constant sorrow: in 1896, his daughter Suzy died. Twain was on the world tour at the time, and was informed by telegram. Twain's wife, Livy, always frail, began her lingering mysterious failure to thrive that was as common in the XIX century novel as amnesia or the evil twin was in XX century soap opera. Today it would be diagnosed and named a polysyllabic syndrome, or given a medical acronym (DMD: Daisy Miller Disorder). Twain was allowed to visit the invalid for only five minutes a day. The Hartford mansion had been sold: too many sad recollections there; Twain imposed upon the household his own restlessness: in 1903, there was a home in the South Bronx, overlooking the Hudson (today known as Riverdale, and specifically, Wave Hill) then a summer in Elmira, New York (Livy's family home) before returning to Europe, and setting up house in Florence. Under such circumstances, it is easy to believe that the essay was "lost in the shuffle." ● Text: "Was the World Made for Man?" Collected Tales (1891 - 1910) Library of America, New York 1992 Vox: Recorded 17 iv 10 / WBAI FM NYC. |

|

Is Shakespeare Dead?

One of the last works published by Mark Twain (in 1909) was his own entry into the field of Shakespeare controversy: Is Shakespeare Dead? Twain enlisted himself on the side of the Baconians, but the book is best thought of as part of Twain’s broad autobiographical project, as Twain demonstrates here a truth about Shakespeare: the more we look at Shakespeare, the more he resembles us! Twain knew his Shakespeare well, and had been introduced to the Baconian claim while a cub on the Mississippi; to a certain degree, his essay on the Shakespeare question hinges upon a concept of celebrity that Twain had pioneered: it is undeniable that in 1909, Twain was the world’s most recognized American. Essentially, Twain compares his reputation with Shakespeare’s, it is an inquiry into the nature of fame. Despite the venom that Twain spits at his presumed opponents, many of his arguments could be used to demonstrate his own peculiar genius, as, for example, their common lack of formal education. Between Shakespeare’s day and Twain’s, there had been quite a change in the perception of fame, and though Twain was justified in believing that his name alone might further sales (or attendance), theatrical operations were simply different in 1600. It was still common for works to be published anonymously, and this tradition continued into the XIX century. Indeed, you may very well wonder why Bacon would go through all the necessary steps to present Shakespeare as the author, when there would have been no penalty or fault if he had simply published without signing his name. That Twain’s fame was based on a pseudonym seems noteworthy now. |

As reluctant as I am to endorse Twain’s Baconian position, I do support the essential premise of Is Shakespeare Dead? -- the astonishing endurance of unquestioned received opinions that is the topic of his essay “Corn Pone Opinions” and can be seen in the romanticized notions Tom Sawyer displays in the liberation of Jim. I think that those prosecuting in favour of one or another claimant pervert the art of reading, but at least they are consulting the texts. The sheer reputation of Shakespeare on the other hand allows many to slip through life without once engaging with either page or performance, a somewhat immeasurable loss. I think the absence of biographical information regarding Shakespeare – or to put it better, lack of a certain kind of biographical information – is really to our advantage, it spares us a good deal of the muck of idle speculation, but at the end, we can only begin to discuss Shakespeare upon experiencing his plays, via page or performance. In the end, we may freely discuss who is the better playwright: Beckett or Chekhov or Aeschylus, but this demands an examination of the works themselves.

In the last decade of Twain’s life, he composed more and more through dictation, a strong link to the art form: radio. In the 1890s, Twain had written to a friend about the pleasure in writing without the informing desire to be published: it was the means to establish the grand freedom of speech that marks Twain’s final years. Something spectacular about these works: often there’s attached at the head some item from the daily news which inspired Twain, and I can hardly avoid mentioning: as Twain did not live into the radio age, we may give thanks that there was a man called Jean Shepherd. Simon Loekle |