|

PROTEUS, Episode III, ULYSSES

The opening paragraph of PROTEUS has often proved a stumbling block to newcomers to ULYSSES, who have only recently accommodated the interior monologue, and who are now plunged deep into the “work in progress” of Stephen Dedalus’s active thinking. And what the hell is he talking about? The oral presentation of ULYSSES streamlines the text, and the passage or phrase that might spark research when met on the page sails by on the breeze of forward momentum. While there are obvious disadvantages to the “audio only” approach to ULYSSES, it is an ideal introduction to any episode, as it highlights the wholeness of the prose. Reading Joyce demands rereading Joyce, and the private and personal experience of the text requires, nay: demands pauses. Raising questions and pursuing meaning are important parts of the Joycean experience, but sometimes it is wise to wait to discover what is resolved within the text before striking off on independent research. (An analogy may be drawn with the movie patron who audibly worries about who and what seconds before [or after] it is made clear on screen.) The Aristotelian references of the first paragraph are meant to recall Stephen’s Aquinine tonic of the PORTRAIT, but in the context of this episode, they are but a small part of what is on display. |

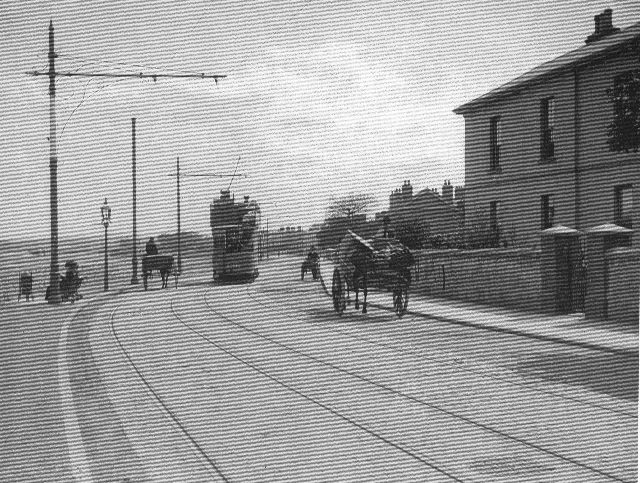

Alone with his thoughts, this is the high point of Stephen’s day, and his sharp memories, shaped by imagination and his command of language, provide us with a series of vignettes, ranging from a visit to his uncle, Richie Goulding, to scenes from his days in Paris, presented with humour and affection. Stephen is as misunderstood by some readers of ULYSSES as he is maltreated by some of his fellows in Dublin. Stephen is not showing off: he is alone on Sandymount Strand, and if his woolgathering seems more directed than those examples from Mr or Mrs Bloom, it is [1] because there are fewer distractions, and [2] because of his pronounced artistic tendencies that sharpen his images. Within an hour, Stephen will begin drinking, and he will keep at it for the remainder of the day (close reading of ULYSSES allows us to tally up his boozing). It is only fair to admit that as a poet, Stephen is far from Yeats, but it is also fair to insist on his youth, and even to go so far as to declare that the artistic temperament may not always discover its proper outlet. Nevertheless, should Stephen never publish a word of his own writing, we are here in the company of an artistic mind, a disciplined mind roving free.

‡ This episode occurs simultaneously with the sixth episode of ULYSSES, “Hades” – just past 11 AM, Thursday 16 June 1904. I hope you will notice the establishing of the date towards the close of the piece, it is an example of a useful thing to look for while reading ULYSSES, time references that confirm the date. As I Please Bloomsday Show, 16 June 2007, WBAI 99.5 FM NYC. |

|

As I Please: Simon Loekle |

|