|

To Accompany COMPANY

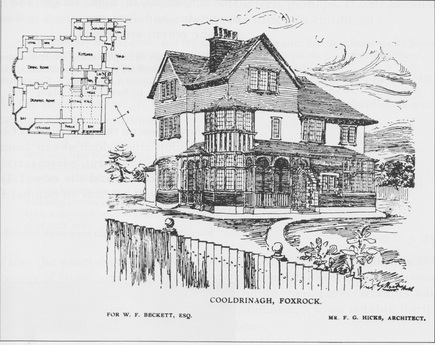

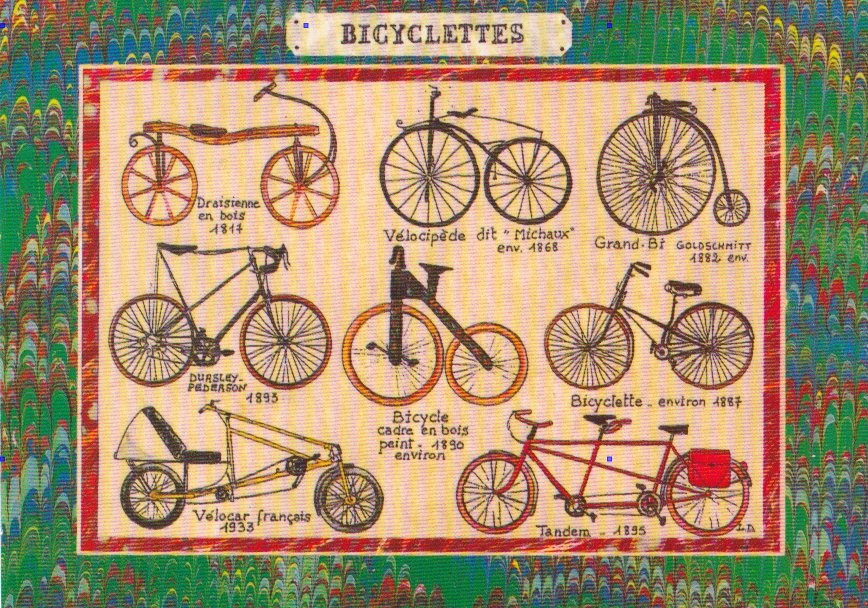

Beckett's late prose trilogy, Nohow On (1989) consists of three short works: Company, Ill Seen Ill Said and Worstward Ho. First, to correct a common misunderstanding regarding Beckett's bilingualism, Company and Worstward Ho were each originally written in English, and were published in 1980 and 1983 respectively. Mal Vu Mal Dit, published in 1981, was translated by the author and the English version appeared in 1982. According to James Knowlson (whose biography of Beckett, Damned to Fame, is a very fine book) the first stab at Company was in French: I think as the autobiographical elements began to take shape, Beckett turned to English as being more companionable. The most direct autobiographical reference is the birthdate of the suffering unnamed character: a Good Friday. There are other slighter references to Beckett's biography, along with the specifics of place-names ("Ballyogan Road" and "Croker's Acres"") that next to the uncertainties of "where now" present an Irish then. Most startling perhaps, especially in the general context of Beckett's placeless and impoverished literary realm, is the mention of a De Dion Bouton, a top of the line automobile in the early days of the XX century. The surprise generated in encountering a privately owned motor vehicle is perhaps exceeded when we learn of the existence of a pocket watch. A working pocket watch. |

The past recalled includes Beckett's past writing. When it is imagined necessary to give the sufferer a name, he is provided with the initial M (Murphy, Molloy, Malone.) The imagined other is to be called W (an M upside down). In the end, it is decided that he is unnamable.

Shakespeare is heard from the shadow, Dante named outright (a reference to Purgatorio IV). Among other proper names encountered in Company, Hodgkins and Pott, are linked to disease. Considering the course of Beckett's prose after the second world war, increasing solitude and reducing mobility, this is a veritable crowd of people, places and things. The constraints of the situation ("you are on your back in the dark") undermine the chance for company. "Another trait its repetitiousness" By my count, including title, the text consists of nine thousand five hundred twenty five words. By my count, including title, "company" occurs 34 times. Repetition, but not without variation. Company itself is affected: "companionable." The action (!) shifts between third person and second person narratives, the third, which we encounter first, presents the throes of creativity, revising and refining the details of the situation. The second, to a large part, presents scenes from a past. Rarely, a first person is also heard. Considering the restrictions of the proposition, language is the field of action, a drama of grammar. And yet, there is opportunity for astonishment: for example, the word "withershins." ("In direction opposite to the usual; the wrong way" OED) Or the nineteen occasions (by my count) where an exclamation point is employed. Twice in the company of "Aha." The comma appears only when separating the third and second persons; in an effort to be as precise as possible, sentences can become syntactical tangles. Such as: "Can the crawling creator crawling in the same create dark as his creature create while crawling?" One of many questions raised through the third person. The text is divided into 59 paragraphs. As noted in Fowler, "A reader will address himself more readily to his task if he sees from the start that he will have breathing spaces from time to time than if what is before him looks like a marathon course." Bearing in mind Beckett's own injunction, "no symbols where none intended" (Watt, 1945), it would be easy to dismiss this as of little consequence were it not for the lengthy meditation on the pocket watch and its sweep second hand. |

STILL Fizzle #7

|

ON PING

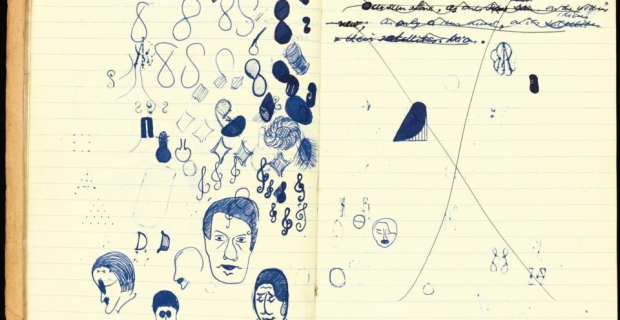

This Beckett piece was first published in French in 1965 under the title, Bing. The next year, in English, as Ping. The name change suggests something other than simple translation; like Irish twins, they resemble each other closely, having the same genetic material, but they are not identical. The name is a nonsense syllable, something to call the object of the text, with as few associations of gender or history or literary reference as possible. Actually, it differentiates the Self from the body that is so painstakingly (though only partially) described. It is an example of Beckett’s kindness, and his sense of the ethical responsibilities of an author, that he would not put Bing through the experience of the text a second time: hence Ping. Just 961 words long, Ping is divided into seventy sentences, though the term sentence is here more convenience than grammatic. Verbs are few and far between; each sentence is defined by its initial (and inaudible) uppercase letter and the final full stop, the only punctuation mark employed throughout the piece. I would prefer to speak of these units of expression as lines of verse, for each suggests a shift, however slight, in the text’s perspective, but sentence will serve. In a piece of so few words, the phrases become familiar, like weathered signposts, through repetition and variation. I say “so few words” because repetition is the key to the piece. The syllable ping is uttered 35 times, if we choose to pronounce the title; the wonderfully ambiguous phrase “almost never” |

is heard eighteen times. Despite the small field that is observed, there is a place for opacity, and our “reporter” has opportunities for both revision and negation, repeatedly undermining the seeming assurance of another common phrase of the

text: “all known.” “All known” does not mean that what is known is all that can be known: it is the sum of knowledge so far. The nonce word “unover” jars the ear, while the archaic word “haught” is something of a surprise, with its implications of upright dignity. The recurring phrase “head haught” always occurs at the top of a sentence. Consult the entry for “bare” in the Oxford English Dictionary and discover the word’s rich history. I have used the word “reporter” to cover the presentation of the text we read, as I think the more common term “narrator” might be misleading. Ping reminds us of one of Beckett’s innovations in theatre, the memorable stage image: the rising hill of sand in Happy Days, the blubbering lips of Not I, the three urns of Play. Beckett anticipated the common misguided complaint lodged against his work in Waiting for Godot, where Gogo remarks “Nobody comes, nobody goes, it’s awful.” Confined to a space of 54 cubic feet, Ping has far less mobility than those cousins who occupy the cylinder of The Lost Ones: the eyes move, but only just, and upon occasion (almost never) Ping murmurs. I hesitate to make this note, as in recent years, the undead bloodsucker imagined by the Dublin born writer Bram Stoker has been transformed into an almost pastoral celebration of teenage angst. Beckett also presents the undead, but his are more closely aligned to the struldbrugs of another Dubliner, Jonathan Swift. |

|

WILD LESSNESS IMAGININGS

[1] The first word recalls the Old English fragment "The Ruin," a poem over a thousand years old which has been described as the earliest English meditation on broken stones. Its elegiac tone is similar to that of "The Wanderer" (whose narrator, "the Last Survivor," foreshadows Beckett's narrative stance, "the last person singular.") Even the collection where the charred manuscript rests allows for a pun that suits Beckett: the Exeter Book. [2] The texture of the prose prompts ruin: twenty-four paragraphs or blocks of words that become, through repetition, as familiar as the walls of a prison cell. The progress of reading is made rough by ellipsis, the only punctuation the full stop. Without those accessory jots and squiggles, words have hard edges; their relations must be seen feelingly. This prose is not for the quick. For whom then? [3] It is the same landscape as "Ozymandias," and alone upright amidst the scattered ruins a nameless blue-eyed creature we deem human (or is that a wild imagining?), of the same species as Shelley's tyrant. Despite the stillness there stirs one touch of vanity: the desire to curse God as in the blessed days. Let us lightly note the fact that whatever immortality Ozymandias today might have is due to the blithe spirit of poesy. "Poesy" is an archaic term, and the OED adds that its use is "chiefly poetical." It is a word that lives among the special brood of readers who may know of Ozymandias, who may have heard of Anglo-Saxon. Indeed, Ozymandias represents two dead tongues: the Greek historian who first transcribed the legend on the Pharoah's tablet, twenty-five hundred years ago, could make no sense of USER-MA-RA, and wrote down the name we know, the enduring fame of Rameses the Second. The power of the text springs from the age-old tradition of rumination on ruins, the declione and fall of cities, of empires, of language itself. |

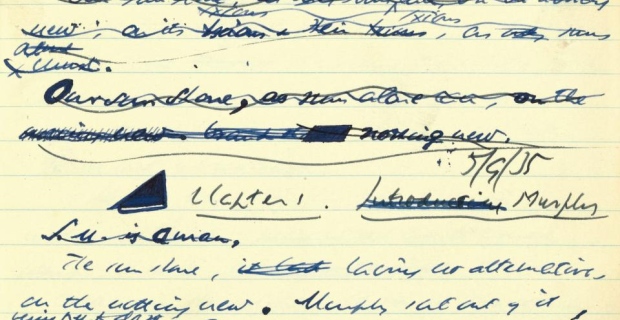

[4] Jack MacGowran described Lessness as the residue of a much longer work; its method of composition begins with its decomposition into six themes, which were wrought into sixty sentences. Their order of appearance and division into paragraphs were randomly assigned (drawn, one would like to think, from a bowler or a toque), and this principle of randomness holds for the repetition of the sentences, the eerie familiarity, like the second act of Godot, similar but not the same. The power of the text hangs between chance and aim.

[5] A puzzling word "lessness," for it would appear to mean possessing the quality of lacking something. "Less" as a suffix sometimes operates as a diminutive rather than a negative, as in the expression "needless to say" which often ironically introduces a not unnecessary statement. So too "doubtless" may contain a little doubt and is not entirely synonymous to "without doubt." As a suffix, "lessness" occurs over twenty times in the brief piece, most often in the word "endlessness" which means infinite or eternal, but also END - LESSNESS. That such ambiguities are intended can be seen in the title Stirrings Still. Are the stirrings ceasing or are there stirrings yet? Is the word C-L-O-S-E in Lessness close (as in near) or close (as in shut)? [6] Dante found his speech feeble and unfinished when he stood within the Eternal Light; it is a moment variously replayed in the works of Beckett, the simultaneous desiring and resisting of speechlessness. This is no arbitrary gag order, but the silence of eternity: timeless, so endless, changeless: when the past and future become our contemporaries, and all stories are one. |

|

NOTE ON BECKETT AND DANTE

The sole proper name mentioned in Beckett's Lost Ones: "wrung from Dante one of his rare wan smiles." Neatness of identification: Dante's smile is prompted by the sight of his friend Belacqua on the slope of Purgatory, and Belacqua is the name of the hero of Beckett's first published fiction, the episodic novel More Pricks than Kicks, the first chapter of which is entitled "Dante and the Lobster." The Dante at hand is Paradiso, notoriously difficult sailing: the image is drawn from Dante's own warning posted at the head of Canto Two. Beckett's fictional world begins with a thwarted approach to heaven. Belacqua's difficulties with the Canti of the Moon (Paradiso: 2 through 5) reminds us of the physical properties of the sublunar world: all that fall, all that fail, all that —. Located between heaven and hell, Purgatory's inhabitants remain conscious of time and obligations; so our modern Belacqua, upon concluding his study period, has things to do: a meal, a scheduled appointment, a required chore, before, presumably, returning to Paradiso for a night's cap perusal. |

The gravity of earthly existence includes the awareness of sin. Dante questions Beatrice regarding the punishment of Cain; Beckett places the condemned murderer McCabe among the first elements of the "real world" Belacqua occupies, once he's closed his book. Real world: there was a man McCabe, whose arrest and trial for arson and murder was widely discussed in the public houses and the press. Like Cain, McCabe declared his innocence. According to legend, God confined Cain to the moon, but McCabe, despite petitions signed, notes Beckett, "by half the land," McCabe was sentenced to hang, duly carried out "without a hitch" on 9 December 1926. So: a date is established: the eighth day of December, Feast of the Immaculate Conception (one of the more misunderstood tenets of Catholicism, and for that matter, one of the more recent, established as doctrine in 1854).

The negative finality of the last words was not exempt from revision. As late as 1986, Beckett wondered if perhaps it would not be more Dantesque to conclude: "Like hell it is." |