|

Shakespeare: spawner of tourist traps

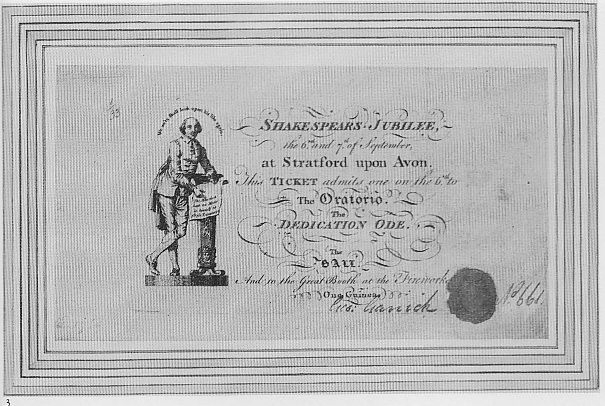

progenitor of conspiracy theorem By the XVIII, the supreme reputation of Shakespeare had settled around the little town where he was born, Stratford-upon-Avon. Stories accounting for Shakespeare’s time spent in Stratford, though few and far between, had achieved legendary status; among the most enduring: the visits he received from his London pals; it’s an old tradition that Shakespeare died, beneath a mulberry tree, after an evening drinking in the company of Ben Jonson. This event was never mentioned by Jonson, but that was hardly a barrier to the creation of the earliest chatchkas of modern secular tourism: products hewn from the supposed mulberry beneath which Shakespeare sighed his last breath. It has been estimated that if all these objects were reassembled to their original state, it would result in a mulberry grove the size of Central Park. It was a period when the plays of Shakespeare were markedly different on stage from what he wrote, improved to suit contemporary standards, and yet no one noticed a contradiction between this repackaging of the plays and the sweet elevation of the poet to veritable sainthood. The great Shakespeare Jubilee of September 1765 was a week’s worth of celebration held in an almost ceaseless rain: when the thing was done, it was observed that not a single line by Shakespeare had been uttered during the entire event. Not long after the Jubilee, the son of a Stratford tour guide, named William Henry Ireland, released a curious literary forgery, the manuscript of a hitherto unknown play by Shakespeare. Samuel Johnson was not taken in, but many were, not because of the Shakespearian qualities of the play, but because of the heartfelt desire to be close to a relic of Shakespeare. These are fair examples of “bardolatry” – a fevered fanaticism orbiting Shakespeare’s life and works. A reaction was bound to set in, and the publication, in 1856, of Delia Bacon’s dismissal of Shakespeare in favour of Sir Francis Bacon begins the curious history of claimants: that is, that someone other than Shakespeare wrote the plays credited to Shakespeare. Since Bacon’s book promoting Bacon was published, there has been a growing queue of claimants, of whom the first (Sir Francis) remains the most famous, though early in the XX, arguments in favour of the Earl of Oxford’s claim began to overtake Bacon. The relative paucity of biographical information regarding Shakespeare has always been a key factor in the history of claimants, to which has usually been added some fabrication to support an urgent necessity for anonymity. Not only has the number of claimants increased to become a veritable who was who at the close of the Tudor Dynasty, continental Europeans

|

have been drafted for the purpose, and the playwright has also been provided with a number of second careers to account for the occasional display of insider professional knowledge. But of all the careers attributed to Shakespeare, the most important is the one for which we have the greatest evidence: an actor and a member of the leading theatrical group of his day, the Chamberlain’s Men, later the Kings Men. How one becomes a great poet may still be counted among the mysteries; to become a great playwright, it is useful to spend some time in the theatre.

Ironically, that quality which suits the dramatist best, the quelling of his own personality in the creation of dramatic characters, became the vexing point upon which the claimants turn, effectively declaring that as no common countryboy could know so well the depths of human nature, the true author of the plays must be an aristocrat. This was more or less the premise for Delia Bacon, who as an American perhaps could have been a bit more loyal to democratic principles, if not the myth of rags-to-riches. In effect, once you have succumbed to the theory that there is a true but secret author, it is just a matter of casting about until you find someone with presumed talent for the role. If an individual claimant should fall short on a point or two, assistance can be drawn from the company of talent that is the wonder of the age. By the close of the XIX, a number of theories involved secret societies, as it were, or phrased with less malevolence, clubs dedicated to the creation of the plays with William Shakespeare serving as the Front. Such conspiratorial theories were given a boost by Shakespearian scholarship: textual analysis at the close of the XIX suggested a far more collaborative effort in Shakespeare’s theatre which has been called “disintegration.” Collaboration of this sort is common in the production of any performance, and working with the same company of actors for over twenty years must in itself be seen as a lucky break for the playwright, they were tops at the time. Bacon’s claim was widely known by the close of the XIX, thanks to champions who spared no rhetorical device to persuade the world it had been bamboozled. The few facts regarding the man from Stratford were used as a mallet against his character, with special attention paid to the lack of a university degree, the notorious last will and testament, and that no particular notice of his death was made at the time. Of course, with enough repetition anything can gain a measure of credibility: how many otherwise responsible and intelligent people do you know who harbour conspiratorial theories? The unfortunate failure of virtually all conspiracy theories is that “neatness of finish” which gilds human incompetence and flaws: it is difficult to credit a conspiracy running over 200 years to conceal the true author of a bunch of plays. After all, is it not evident that human beings have difficulty keeping their mouths shut? Simon Loekle |

|

As I Please: Simon Loekle |

|