|

Cyclops, by Shaw!

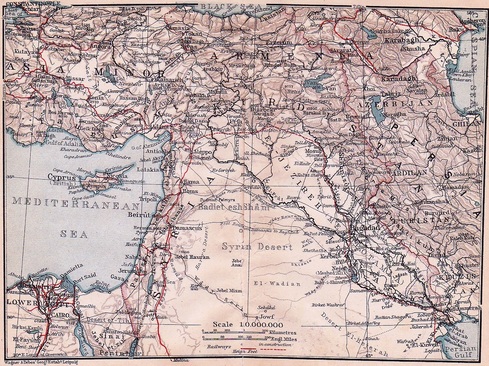

The project to translate the Odyssey was proposed to Lawrence by Bruce Rogers, one of the great typographers of the XX. Rogers wanted to produce a fine limited edition, but was unsatisfied by available translations, such as the Victorian Butcher-Lang, and Samuel Butler's 1900 version. Then came the brainstorm, that the author of Seven Pillars of Wisdom might provide a translation of merit. Lawrence was on the other side of the world at the time, stationed at the RAF base in Karachi (then part of India). However, Lawrence was pleased by the offer, which came with the promise to pay an honorarium of ₤800, a tidy sum for someone living on the meagre salary of an enlisted man. Furthermore, the Odyssey was a book Lawrence rarely travelled without, though he admitted to being no scholar, "I read it only for pleasure, and have to keep a dictionary within reach." Not the least factor in governing Lawrence's acceptance of the job was the chance to work with Rogers himself. As a student at Oxford, Lawrence had dreamed of entering the printing trade, with goals similar to those of Bruce Rogers, and Lawrence had supervised almost every aspect of the production of the first, limited, and privately printed edition of Seven Pillars. (Lawrence approached Wyndham Lewis to provide sketches for the blank spaces at the end of chapters, "I don't like such voids" but though Lewis was paid ₤50 in advance, he did not fulfil his commission. Like Odysseus, Lawrence crossed paths with a wide variety of characters; indeed, Rogers' proposition was conveyed to Lawrence by Ralph Isham, who had consulted Rogers regarding the forthcoming publication of Boswell's journals.) Lawrence began work on Homer in the Karachi barracks in 1928; it would be published in 1932. ●

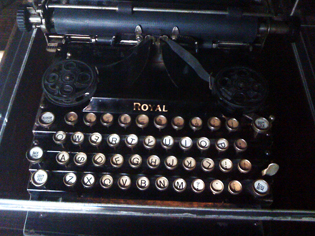

Before Lawrence could settle into his translating work, he was transferred from Karachi to a small outpost on the Afghanistan border - the smallest in India - where his duties were mostly clerical ("I am the only airman who can work a typewriter"). Lawrence welcomed the change: his workload was easier in Miranshah than in Karachi, and "the quietness," he remarked, "is so intense that I rub my ears, wondering if I am going deaf." After a month's work, he was able to send off a draft of Book One to Ralph Isham [30 June 1928]. In the letter accompanying the typescript, Lawrence once again declared that he would not be at all offended if the sample led to rejection: it is a sentiment that occurs often in his correspondence regarding the Odyssey, modestly declaring that he was no match for Homer ("a very great poet"), modestly declaring that he was unfit to be published by an artist like Bruce Rogers. There are numerous occasions when Lawrence declared that he was only in it for the money (by the common formula, ₤1 was equivalent to $5: a generous amount in 1928) but it is best to take such statements with a bit of salt. Lawrence's remarks on developing a style for his Homer are of great interest, trying to find a balance between the forward momentum of narrative and the load of details provided in the original: "He does describe every cup of wine, every man, every wave, of the world. Intolerably slow, and yet so delicate, so subtle, so sophisticated, so civilized." At one point, Lawrence requested that some scholar of ancient Greek take a look at the work in progress, as he (Lawrence) was anxious to avoid any howlers, but even Lawrence was forced to admit that the Cyclops episode was very good.

|

Lawrence, again with characteristic modesty, described the project as the 25th Odyssey in English, for which no one held his breath; the work was slow-going as when "after a cycle of alternatives one returns to the original word." The trick, as we might call it, in translating Homer, is to bear in mind that Homer was not writing about contemporary events, (Sophocles would have considered Homer ancient): a sense of past grandeur is a necessary component to the text, though the translator should not fall upon the easy out of old-fashioned (Wardour Street) English. It is a tight rope, to serve the text, maintaining the integrity of the original while simultaneously seeking to make it new.

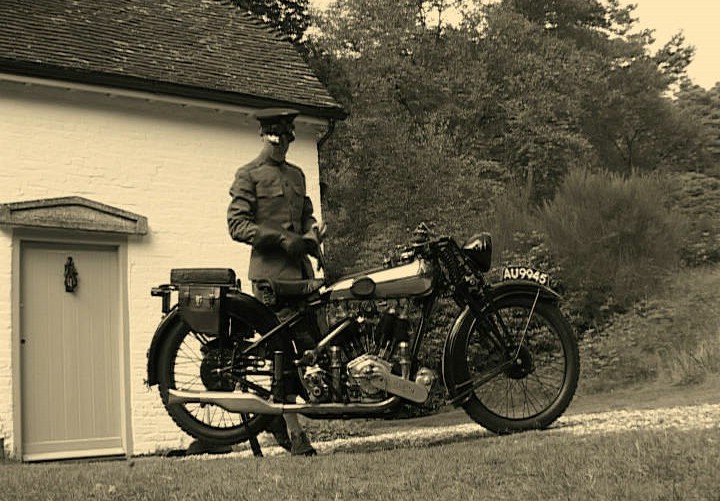

The tight rope seems a suitable analogy for Lawrence, once his career had taken its celebrated turn in the Arabian campaign. One of Lawrence's conditions upon accepting the Homer job was anonymity; he had changed his name to Shaw, but his identity was, at best, an illkept secret. Lawrence's post-war career seems driven by a desire to escape the glare of celebrity, but he was always known, recognized and followed. At the close of 1928 a thoroughly false account of his activities on the Afghan border published nearly worldwide by newspaper syndicates, resulted in Lawrence being reposted to England, which disrupted the Homer work for a few months. It was not the first nor last occasion when rumour would attribute to Lawrence fantastic facility for disguise and languages and undercover operations. As if the facts of the Arabian Campaign were not fantastic enough. Lawrence was not a modernist; he was among the last Victorians. (Another Victorian, Winston Churchill, outlived him by almost 30 years — when Lawrence first encountered Churchill, in 1918, he was already an established Tory windbag.) I do not mean to suggest that Lawrence was a troglodyte clinging stubbornly to an outmoded perspective: his contact with Wyndham Lewis is a sign of his knowledge of one aspect of Modernism; that he purchased two copies of the Shakespeare and Company Ulysses is another. His posting to the Indian hinterlands was enlivened by a gramophone sent by Mrs George Bernard Shaw (Lawrence was especially fond of Elgar's Second Symphony). And he embraced the more rapid devices of the XX: speedboats, aeroplanes, and motorcycles. (Despite the implication of the bio-pic Lawrence of Arabia, Lawrence had fallen under the spell of motorcycles while stationed in Egypt in 1915; he rode a Triumph then.) T S Eliot once said that "every age is an age in transition" and I suspect Lawrence knew this from the very depths of his soul, committed, as it were, to maintaining a sense of honour and duty that had been jostled out of place by the Great War. In 1925, as he was nearing completion of the Seven Pillars, he read Eliot's collection of Poems 1909 - 1925. "It's odd, you know, to be reading these poems," he wrote, "so full of the future, so far ahead of our time; and then turn back to my book, whose prose stinks of coffins and ancestors and armorial hatchments. Yet people have the nerve to tell me it's a good book! It would have been, if written a hundred years ago: but to bring it out after Ulysses is an insult to modern letters — an insult I never meant of course, but ignorance is no defence in the army!"

● The book was published in 1932 without a translator's by-line. However, the translator at last conceded to provide a note, printed at the tail of the book, over the name T.E. Shaw.

The piece is brief, but potent. The project had required nearly four years to complete; he writes with the affectionate intimacy of cohabitation. The textual errors or flaws that Lawrence mentions must be taken in the context of Homer's antiquity: astonishingly few for "the oldest book worth reading for its story" — I for one can not help but think of Joyce's Ulysses, and the typos still to be found there. It is astonishing that a "true live" adventurer would translate the adventures of Odysseus; that the translator had also been an archaeologist, at home in worlds lost to time is no less astonishing. (And add this to your list of literary might-have-beens: in 1923, Lawrence entertained the notion of translating the Arabian Nights.) -Simon Loekle

|

|

As I Please: Simon Loekle |

|