|

Time: 8:00 A.M.

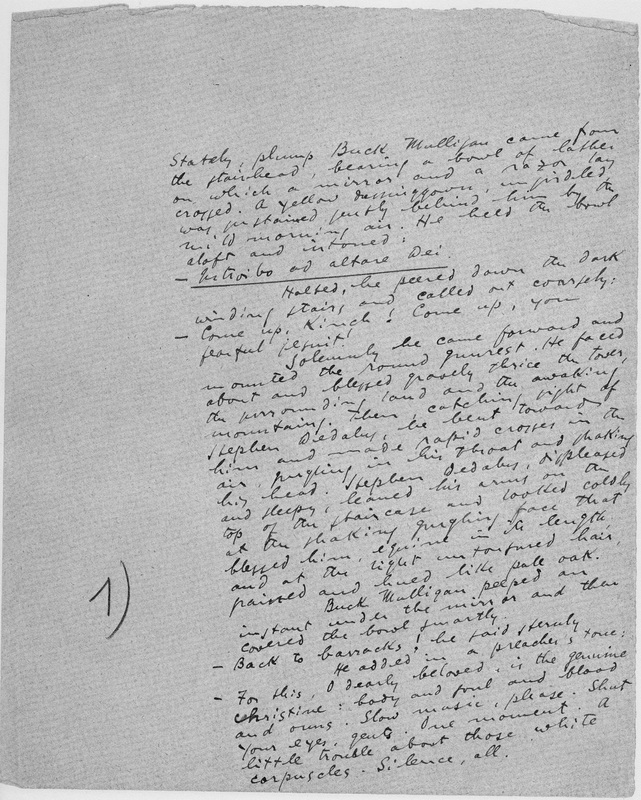

Place: Martello Tower, Sandycove, Dublin, Ireland Career Opportunity: Parasite, flunky It is usually said that Ulysses grew by one-third through the proof stages; every episode shows signs of this revisionary evolution. Telemachus is no exception, though only lightly touched: corrections of typesetter errors, some refinements, a few additions, of which the most notable might be the introduction of the phrase "agenbite of inwit" (I:481) in the second proof. The passing cloud, sign of the simultaneity of the first six episodes, is there, and a reference to the "sweet young thing" (684) who is none other than Milly Bloom. On the whole, this gives credence to the notion that Ulysses was conceived as a vision, its wholeness (or integritas) evident to Joyce from the start. Telemachus reintroduces Stephen Dedalus, whose character and habits of thought had been established in the earlier novel, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Technically, then, Ulysses is a "sequel," but Stephen is now employed in a secondary function, serving the interests of Bloomsday. Consider cattle, which will horn in on Stephen's day at the insistence of Mr Deasy in the next episode, and are the concern of one of Bloom's civil improvements (and receive the distinct honour as title role for episode XIV, Oxen of the Sun). In a rare Joycean evocation of rural Ireland, we have here "Silk of the kine and poor old woman" (403). The beasts gather satiric weight in association with Oxford: "Don't you play the giddy ox with me!" (171) Another addition to the episode, also introduced at the second proof, ties together three motifs found in Telemachus: Mulligan, whose face is "equine in its length" (15), cattle, and Haines, the foreign guest: three things provoking caution: "Horn of a bull, hoof of a horse, smile of a Saxon." (732) Stately plump Buck

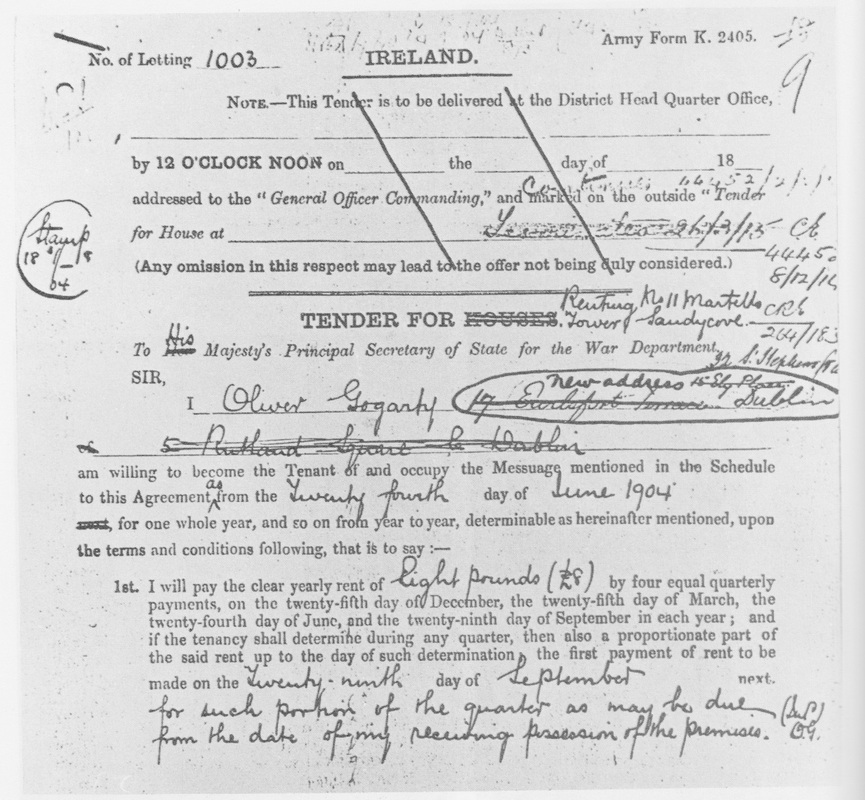

We must allow that Buck Mulligan is an entertaining fellow, and would offer sparkling company. His ready smile, quick wit, cheerful blasphemy are social qualities that conceal a shallow and opportunistic character. His has been a life of comfort, thanks to the indulgence of his aunt; if he exudes a sturdy self-confidence, it is because he can afford to, at little cost to himself. Following the invaluable lead of Hugh Kenner let us tarry on the phrase that introduces him: it does convey a sense of luxury, the man's wellfed and carries it well. "Plump" is often used to describe a baby's cheeks (upper or lower); later in Ulysses, Hugh Boylan is seen lifting "plump red tomatoes" (X: 309: beefsteak or plum?); Mr Bloom will kiss his wife's plump rump (XVII: 2241). It does not seem commonly applied to the physique of a grown man, but does suggest a less rounded figure than stocky, portly, chubby, or fat. Consulting Skeat's Etymologies, we find these more obscure, now obsolete, senses: clownish, blunt, coarse. When Buck calls out to Stephen it is "coarsely" (7). "Plump" is also imitative of the sound when entering a body of water, with such clean fun the episode concludes. Malachi Roland St John Mulligan (XIV: 1213) called Buck by all, except, I suppose, his aunt. It is the first of many nicknames we encounter in Ulysses. The primary sense of "buck," a male deer, strikes me as inappropriate, as the image of the stag who flashes his "antlers on the air" Joyce had applied to himself in the satiric poem The Holy Office. It clearly stems from the XVIII century use, meaning "dandy, fop" as demonstrated in "God, we'll simply have to dress the character. I want puce gloves and green boots." (515-16) There is also a vulgar sense, "to copulate," cited by Mulligan himself: "Redheaded women buck like goats." (706) Villain may be too strong a word in the context of Ulysses; there is some justification in ascribing Stephen's sensitivity to a particularly acute hangover, but as the day proceeds, the distance between the two young men widens considerably. The comprehension of Ulysses is in good measure a retrospective arrangement, that is to say, the rereading of Ulysses. So, it is in subsequent readings that we develop the required cold eye to view Buck's blathering charm with suspicion. "Equine" distantly suggests the Trojan Horse, mistaken as a gift. Buck is kin to Iago. A moment of Stephen's interior monologue still seems to cause some to stumble: "He wants that key. It is mine. I paid the rent." (630-31) It has always been evident to me, from my first reading of Ulysses (in 1967), that Stephen here imagines the ultimate argument Buck might present in claiming the tower's key. At ₤12 per annum, the rent is beyond Stephen's means, even if he is currently employed: he will receive his third salary payment in Nestor, his last in Mr Deasy's employ; if there is one thing we can say with certainty about Stephen Dedalus, saving is not his strong suit! No, the lease is assuredly in Buck's name--even if the aunt pays the rent. [Note on Gogarty] Elements of Style

Homeric associations may not be immediately apparent in Telemachus, but the "interior monologue" is. The shift between inner and outer is remarkably fluid, creating a parallax of style; the technique was noticed and discussed while Ulysses appeared (serialized) in the Little Review. Upon publication in 1922, this was a widely known feature of the text. It appears first on the very first page of Ulysses, but so subtly that it is sometimes overlooked: the single word |

"Chrysostomos." (26) Placed between two sentences of straightforward narration, interior monologue is introduced with a pun: "chrysostomos," Greek, "golden mouth" refers to the glistening gold visible between Buck Mulligan's parted lips. The term is equivalent to "silver tongue;" it is commonly associated with the beloved disciple St John and his rhetorical prowess. (Please refer above to Mr Mulligan's full name.)

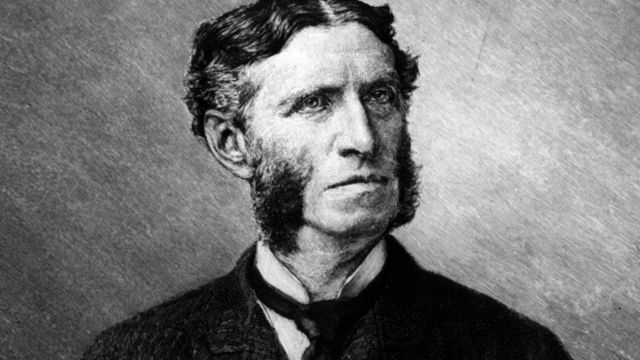

Stephen is not at his best this morning, another 75 lines unfold before we have access to his thoughts again, and then only after the narrator has carefully established a context. Even then, it is not so much thought as a kind of vision, as Stephen "rhymes" his view of the bay with the white china bowl at his mother's deathbed. But from here on, we have easier access to Stephen's uneasy thoughts. The function of narration is to represent the Outer World, the sky, the sea, what people have to say; this function is expanded by the Inner World, via the internal monologue (usurping an element of traditional narrative). To this add an Under World: the Homeric foundation, and we have a tridimensional frame of reference. The Homeric associations are unperceived by character and narrator(s): recognizing them is the reader's duty. There is as well a fourth dimension: Time, mostly memory (there is little serious speculation of the future in Ulysses, though Bloom's suburban dream is endearing). With Stephen, memory often takes on a visionary quality, and I think Vision aptly describes the debagging scene (165 - 175): this is not Stephen's personal experience but a recollection of one of Buck's anecdotes, revivified through the agency of Stephen's imagination. We will note this quality many times in Proteus. The presence of Matthew Arnold is, I believe, pure Dedalus.

According to the scheme of Ulysses as published in Stuart Gilbert's guide, the technique of Telemachus is "Narrative (young)." Each of the three parts of the novel open with an episode featuring a Narrative technique: Calypso, Narrative (mature); Eumaeus, Narrative (old). A sign of the youthful energy of Telemachus is the frequent use of exclamation marks, which did not see print until the Gabler edition of 1984, though they had existed, for all the world to see, in the Rosenbach manuscript residing in Philadelphia. (When the manuscript pages reached the typing stage, it is best to recall that c. 1917, not every typewriter was equipped to imprint an exclamation mark with a single stroke.) They are chiefly employed by Buck Mulligan, and had the points made it to the first edition (and for that matter, to the Little Review) no doubt Wyndham Lewis would have complained about them; instead he latched on to the "many clichés" to be found, even in the first pages of Ulysses, noting that Stephen Dedalus "does everything wearily." Lewis was the first of the "Stephen-haters." On the first page of Ulysses, we find that Buck speaks "coarsely," "sternly," "briskly" — I take this as another indication of the episode's youthfulness; as Hugh Kenner observed, we are but a short step away from "Tom Swifties" and who better evokes youthfulness than Tom Swift? Lewis was a bright mind, but stumbled on something he did not fully recognize: Joyce's stylistic subtleties to suit the occasion. Joyce may have been uncertain just how far he could take style when he began Ulysses, but the idea of stylistic variety was part of his original conception.

The last instance of interior monologue in Telemachus is, like the first, a single word. "Usurper." (744) An Impossible Person

Buck hits the nail on the head. Though an expression of Buck's pique, "an impossible person" (222) has played an important part in Stephen's critical heritage. His habit of abstract or arcane reference has brought many a first time Ulysseser to a halt, and Joyce, keen to avoid any hint of sentimentality, brings forth numerous unpleasant characteristics about the young man. He is dirty and dishevelled and drunk much of the day; it seems impossible that, aged 22, he could possess the kind of knowledge he displays. As the hero of a novel called A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (which really is not his fault), he is criticized for the paucity of his production. He seems well on his way to the paralytic failure that blights so much of Dublin life (as presented in the works of James Joyce). Buck refers to Dedalus as a bard (73); it is a mocking jibe. Through the course of the day, Stephen is sometimes called a poet, which he does not deny, but outside of the privacy of Proteus, he makes no such claim, and Proteus is charged with self-mockery. I have known many who, offering far less than Stephen, have made much more of being an "artist." The first literary reference of Telemachus, a passing glance at Shakespeare and Oscar Wilde, is made by Buck Mulligan (143); about 100 lines later Buck quotes three lines from Yeats. Did he know, and subsequently forget, that Stephen sang this song to his dying mother, or is it an instance of his callousness? Hamlet is mentioned, but we get neither word nor thought from Stephen on the topic. Is it not noteworthy that the first "literary reference" we have from Stephen is to the pantomime, Turko the Terrible? (260 - 262)? It arises in association with memories of his dying mother, and is distinct from the high-brow allusions for which he is better known. It is a tender moment, somewhat like that when he crosses paths with his sister, Dilly in Wandering Rocks. The "horde of heresies" (650 - 665) are necessary to arm himself against the sea of Dublin troubles. Stephen is alone. He acts aloof. --Simon Loekle |

|

As I Please: Simon Loekle |

|