|

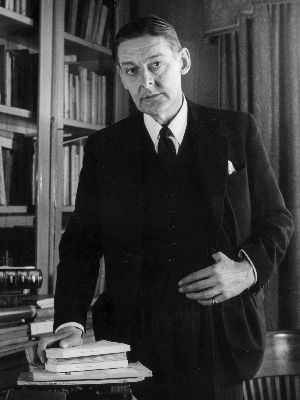

Eliot's Byron

T. S. Eliot's essay on Lord Byron (1937) is a wrongheaded mismatch of sensibilities, yet by turning some of Eliot's points upside down, it need not be dismissed entirely. Eliot, who became a British citizen, who joined the Church of England, who was member to exclusive clubs strikes me as incapable of handling Byron's deeprooted and habitual dissent. Eliot's calling Byron "Scottish" rather than a "Scot" (on the grounds that Byron wrote in English) is a calculated insult — though Byron was as ambivalent on the matter as Eliot was regarding his St. Louis origins (Wyndham Lewis considered Eliot "Bostonian"); his crack suddenly illuminates Byron's lifelong role as outsider. When Eliot wrote, the idea of an independent Scotland was unimaginable, but I suspect that Byron would have enthusiastically championed "a nation once again." This would not please a Tory like Eliot. Eliot admits to a certain apprehension in returning to the Byron's poems, a "boyhood enthusiasm," but (grudgingly perhaps) pronounces Byron "readable." He lightly praises Byron's gift for narrative (not generally counted among Eliot's strengths) and his highest praise is that Byron is never boring. Eliot writes: "Of Byron one can say, as of no other English poet of his eminence, that he added nothing to the language, that he discovered nothing in the sounds, and developed nothing in the meaning, of individual words. I can not think of any other poet of his distinction who might so easily have been an accomplished foreigner writing English." By 1937, Eliot had fully mastered this kind of pontifical phrasing: the trebled "nothing" neatly undermines both "eminence" and "distinction" but I am left wondering what, exactly, Eliot expected from a poet who had not read The Wasteland. (Of "accomplished foreigner," I imagine Byron responding, "Thank you.") Eliot notes changes in poetry since Byron's birth (1788); he does not mention that Poetry as "popular entertainment" was rapidly being taken over by the novel. It is fair to say that Byron,

|

however weak in theory, recognized that a poem could provide a thrill the novel could not. It is true, I think, as Eliot says, that Byron is too often admired for those soaring passages when he is trying to be, in

Eliot's phrase, "poetic." But, these are occasions when he is employing the "special effects" of verse, and allowing for the fact that such effects were more or less expected by his first respondents, the emphasis should properly be placed on "occasions" —. If, over 200 years since the publication of Childe Harold, Childe Harold appears old-fashioned, there is yet something to be learned in the variety of tone and form employed throughout. I think, and I think Eliot would here agree, that Byron is at his best as the seemingly casual digressive tour-guide, the "accomplished foreigner" — a quality which achieves true greatness in Don Juan. Eliot overlooks that Byron is fundamentally a satirist, far closer in spirit to Swift and Pope than to his friend Shelley's more speculative and romantic jottings. What Eliot fails to acknowledge is that Byron is funny — very funny. Consequently, he may not always be "entirely sincere." I would suggest that Byron's genius is the refreshing freedom of speech that so captures the spoken language of his time. Coleridge achieves this in his "conversation" poems ("Lime Tree Bower") — it is a quality that becomes more and more dominant over Byron's career. The Byronic stanza (A-B-A-B-A-B-C-C) proved perfect: flexible enough to accommodate digression, yet taut enough to prevent the poem from sagging. (I should note that the stanza can also be used more "seriously" — see Yeats: "Among School Children")

--Simon Loekle

|

Eliot Links