|

Shem

Like any sport, Waking requires work. Considering the physical damage one risks throwing a hidebound ball 90 mph, Waking is easy. The Wake is as meaningful and as pointless as a baseball game, though perhaps more consistently exciting. Waking demands all the skills and arts of reading, but Finnegans Wake is, in good measure, a satire on literary scholarship. We who Wake keep the joke alive. [1] Ear Waker Oral presentation (Fritz Senn once said) "streamlines the text," eliminating the hands on engagement with the prose that is at the heart of Waking. Listening, or EarWaking, highlights a forward momentum (there's a lot of backtracking while Waking) that offers a sense that sounds much like English with a healthy Dublin tang. Or perhaps it is better to say performance creates the illusion of forward momentum. Joyce! Always inventive in thwarting the usual conventions of narrative; despite the hyper-active prose, there is an odd stillness from chapter to chapter: the consequence of the inconsequence of sequence. This is a condition of the book's cyclical format: it is well-known that the Wake opens by concluding the sentence with which the Wake closes, and it is this cyclical, or more accurately spherical, structure I refer to when I describe the Wake (with profound affection) as pointless, for a traditional novel would offer a beginning, a middle, and an end. The many many lists we encounter in the Wake bring "narrative" to a halt, as does the astonishing elastic syntax Joyce employs. A story, of sorts, is being told, but in a roundabout way. In the phrase used to describe the summer blockbuster, Finnegans Wake is "explosive!" — a book which both expands and undermines our notions of the novel. [2] Shem as Writer/Writers in "Shem" Shem is the middle child of the Earwicker household; his older brother is Shaun, his younger sister is Issy, his parents Anna Livia and Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker. The chapter appears to be a biographical essay on Shem, who is a writer, but it becomes rapidly evident that this account is intended as an exposé: we are meant to be repulsed and disgusted by Shem. This portrait of the artist is as unflattering as can be imagined; ultimately we may choose to believe that it has been written by his brother, Shaun. The rivalry (if not outright war) between the brothers is a frequently re-enacted theme throughout the Wake. By no means is the Wake a traditional novel, yet it has its own internal conventions. In an episode about a writer, Joyce evokes the names and works of many writers. Such literary references (if they can be so-called) are common throughout the Wake, but are found here to a somewhat different purpose. A writer whose presence might be detected by an EarWaker is Jonathan Swift (a frequent visitor at the Wake): listen for Vanessas and Stellas (and variations); Swift, in literature as in life, stands in the shadows behind them. Shakespeare too may strike the ear, the ever popular man of |

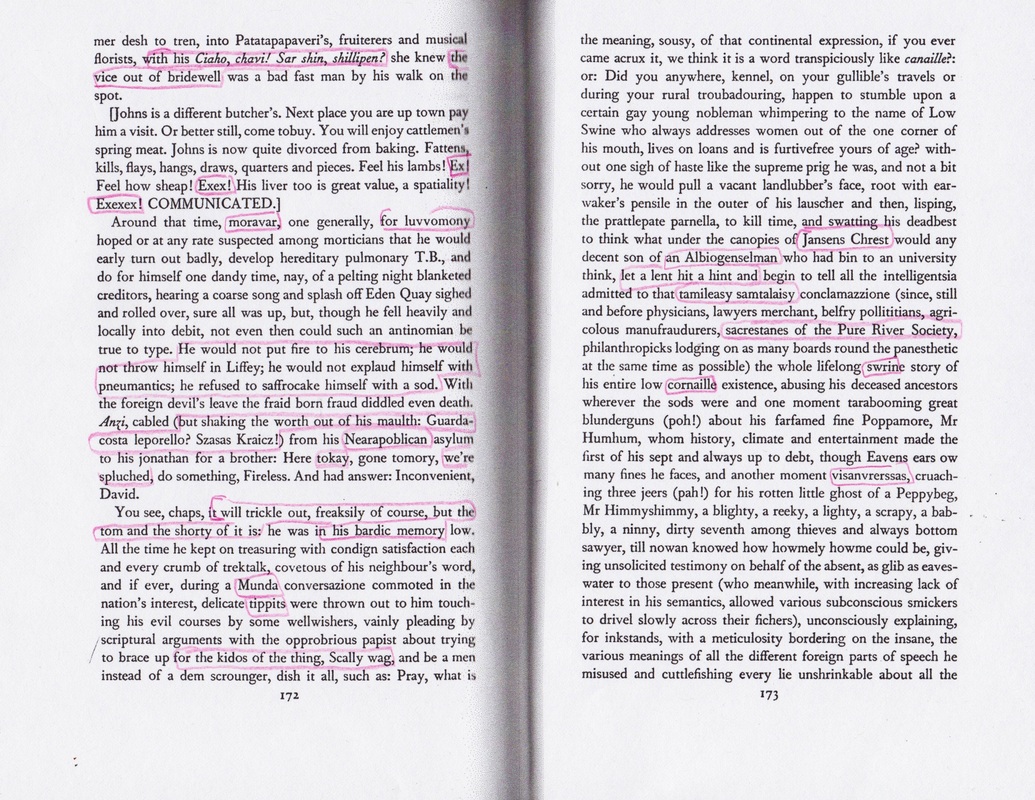

mystery. Perhaps less audible, but a strong presence throughout the chapter is James Macpherson, who claimed to have found the manuscripts of the legendary bard, Ossian. Each writer is here on the strength of his less scrupulous characteristics: Shakespeare, for example, is still widely thought to be not the author of the works attributed to him, while Macpherson's Ossian has long been recognized as a fraud and a forgery. Swift, a master manipulator behind the scenes, published nothing over his name, and while secretly married to Stella, carried on a long term affair with Vanessa (the names by which these women are known were pseudonyms bestowed upon them by Swift). But above all, we find references to the life and works of James Joyce himself (Shem/Shemus: Jim/James). Joyce seems to have made use of every whisper of gossip ever brought against him, and the numerous allusions to numerous "bad reviews" he had received add to the vituperative glee of the chapter. This portrait is informed by invective, innuendo and malice.

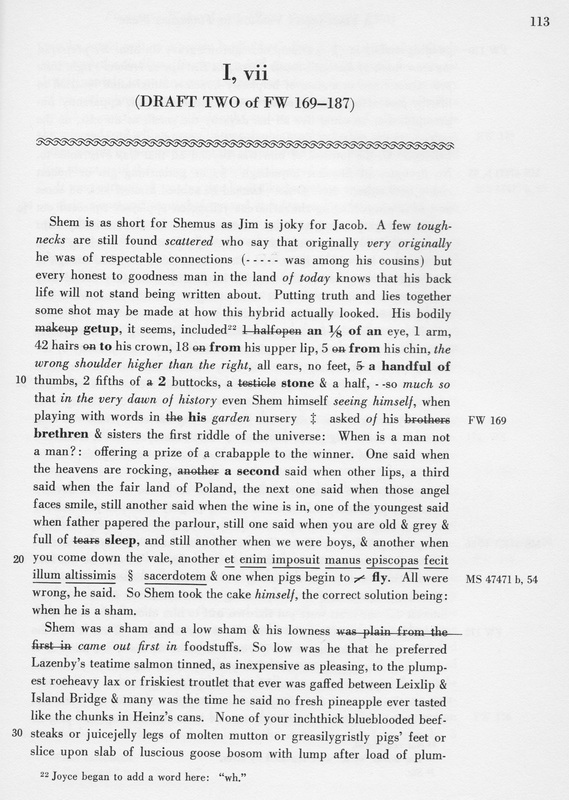

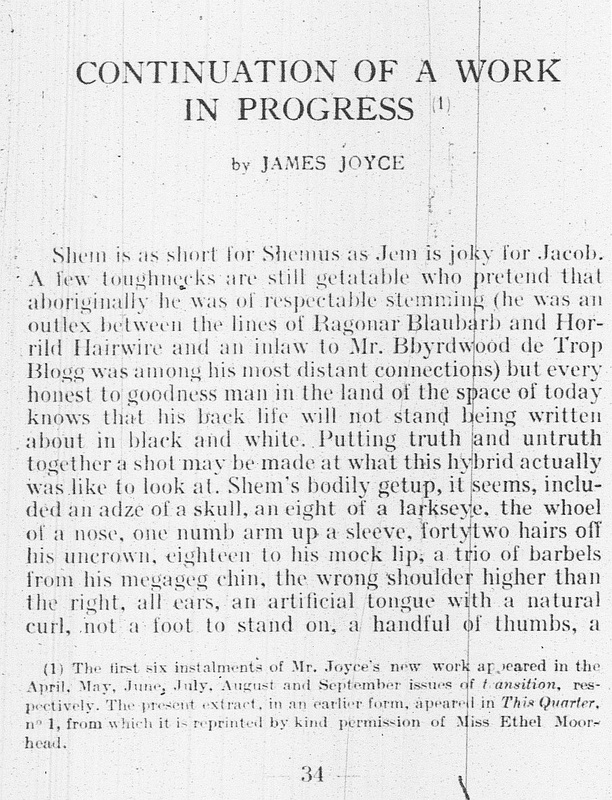

[3] How Come—?? Typically(!), the chapters of the Wake were composed passage by passage: the initial work on Shem was completed fairly quickly in 1924. Then began the elaborate process of expansion. Time is not of the essence at the Wake. Unlike ULYSSES, which was confined to a particular place and specific time, the Wake was conceived as open and inclusive, so once Wyndham Lewis published his notorious "attack" on ULYSSES in 1926, Joyce was free to respond: the Joyce/Lewis feud is a means of dating the progress of Wake Work. Knowing something about its composition is invaluable to apprehending the Wake: its deliberate democratic purposeful obscurity. Indubitably Dublin, the Wake can't help but be internationally urban. Trieste-Zurich-Paris 1914-1922, reads the last line of ULYSSES. In Shem, there are about 18 Hungarian glances or glosses, and I don't doubt they were all incorporated in one fell swoop, his Hungarian-English glossary before him. Bloom was part Hungarian; Trieste, when Joyce lived there, was the access to the sea for the landlocked Austrian Hungarian empire; Hungarian is a language unrelated to its neighbours' (symbolic in connection with Shem, evident in the language we find at the Wake). Note: I am not fluent in Hungarian; I saw "tokay" (a sweet Hungarian wine) and followed up by consulting fweet.org. This is an example of what is missed by the EarWaker, but it is just as well to have an inkling of Wakean conventions. There is still plenty EarWaking will catch. |

SHEMIANA

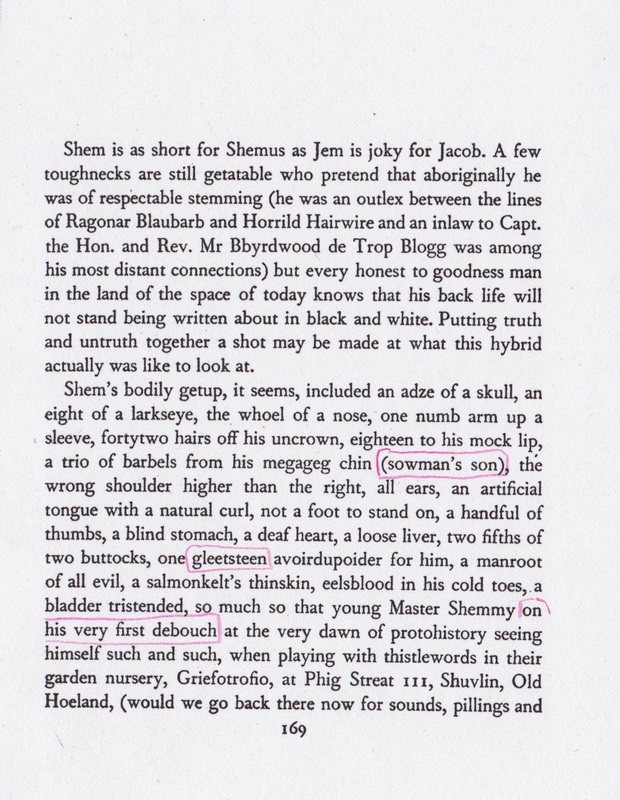

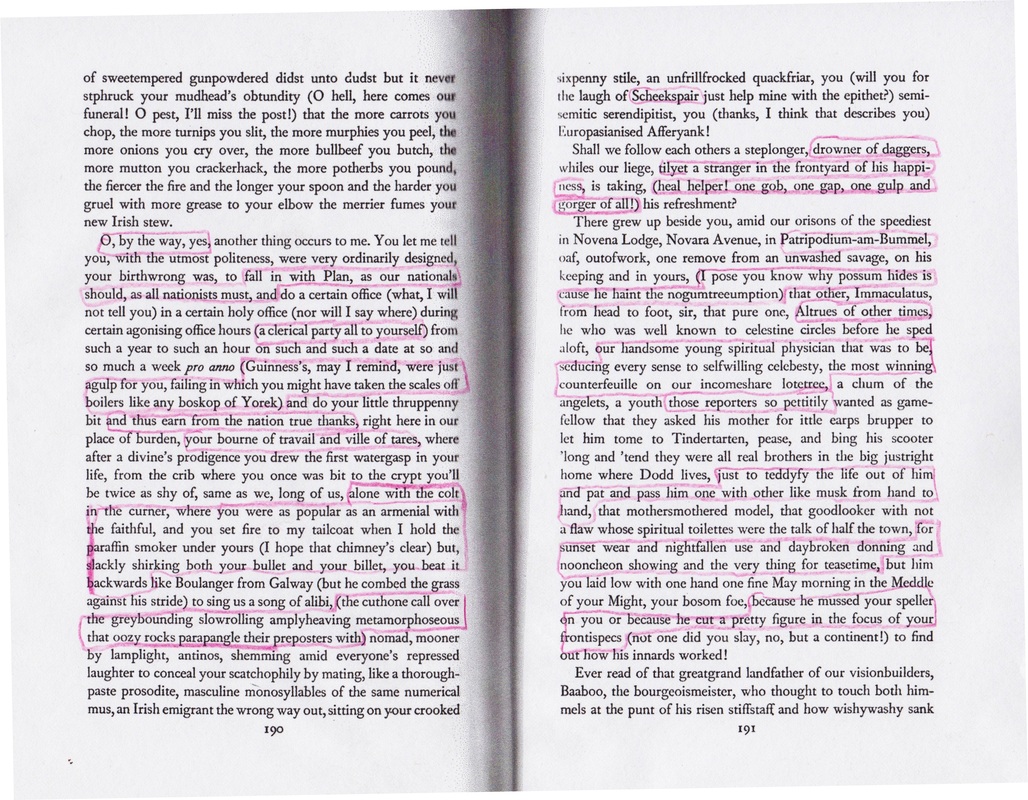

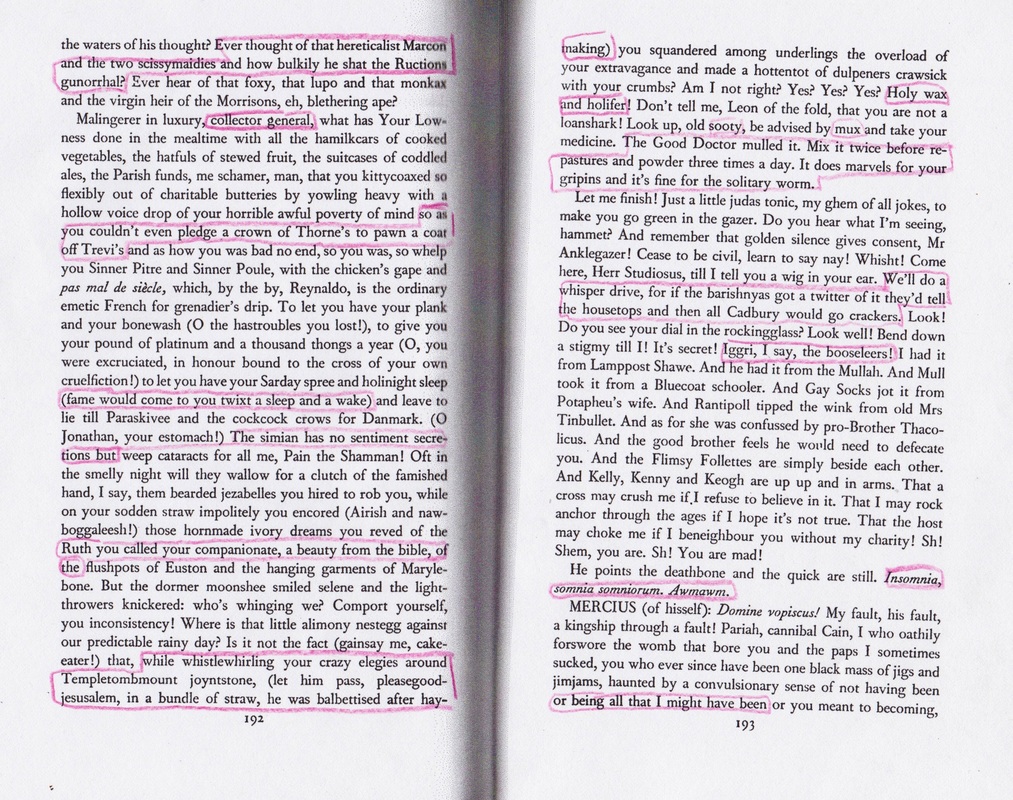

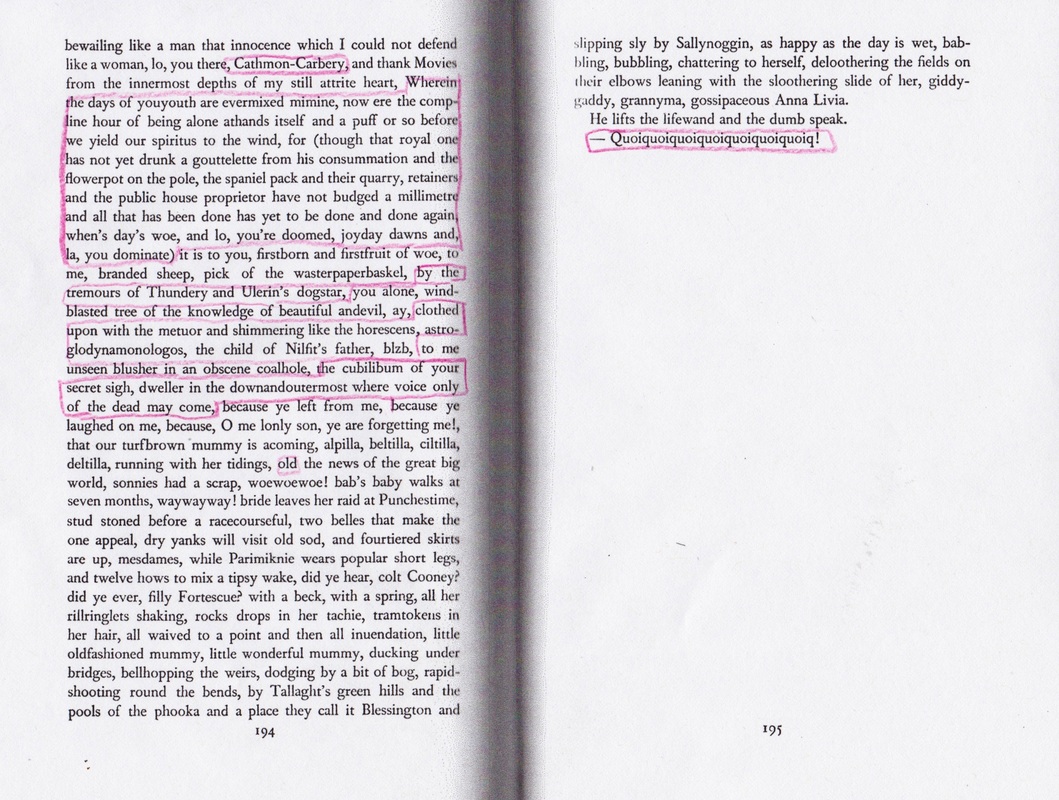

The bracketed material represents changes to the Book of Shem (Finnegans Wake, I vii) between its appearance in transition (October 1927) and its publication in book form (1939). For the most part, Joyce saw the proof and galley stages of publication as an opportunity to add material, but there were occasions when Joyce discovered "le mot juste" — "gleetsteen" on page one of Shem was, in transition, "gladstone." One can hardly imagine a better name than transition for the journal where Work in Progress was serialized for so many years. Even though the text was fundamentally established in the 1950s, when Joyce's corrections were incorporated in the published volume, the nature of the prose runs against finality: it is seemingly always in transition.

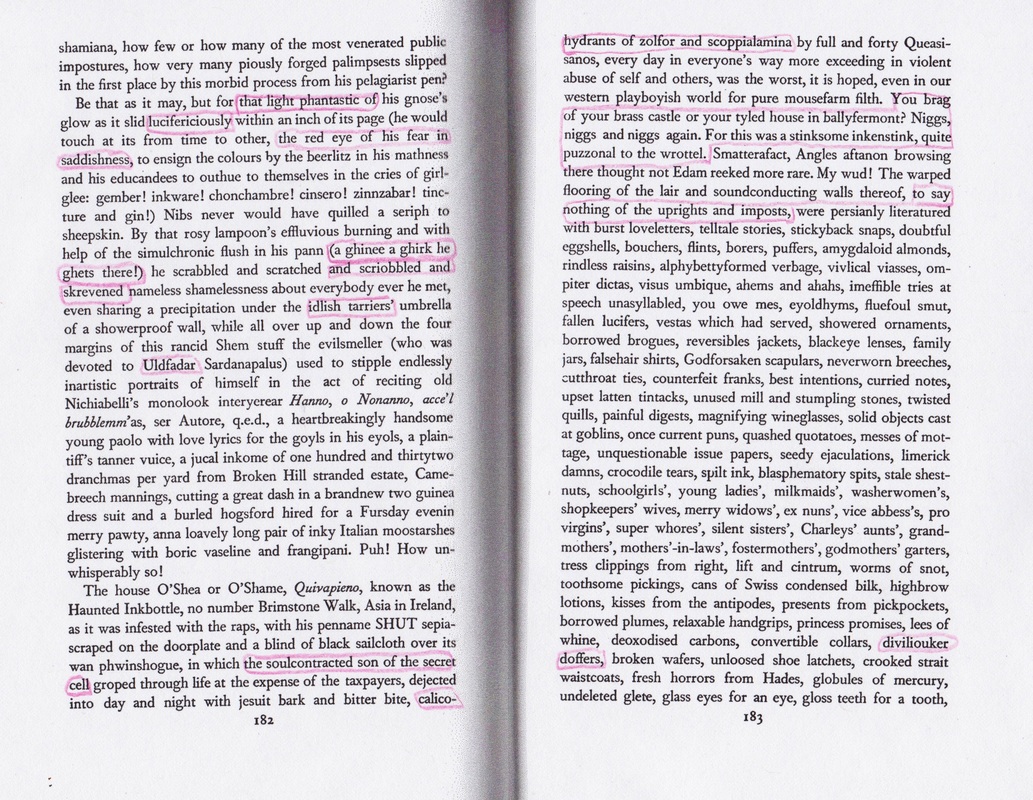

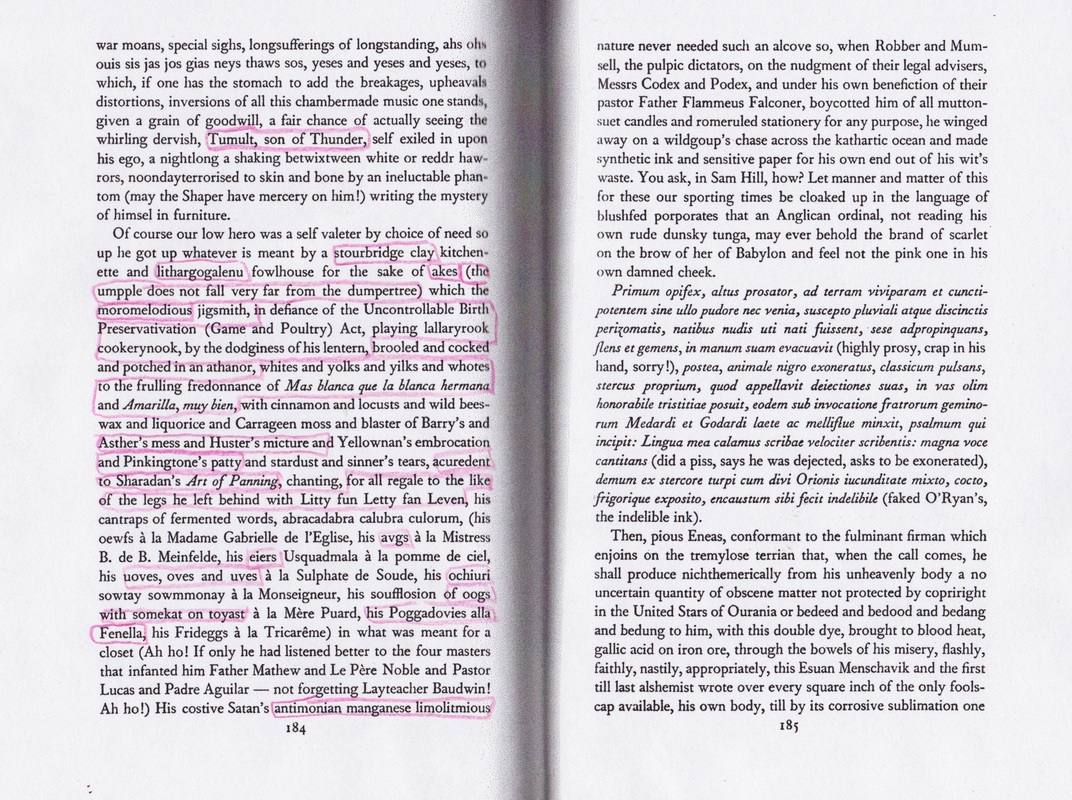

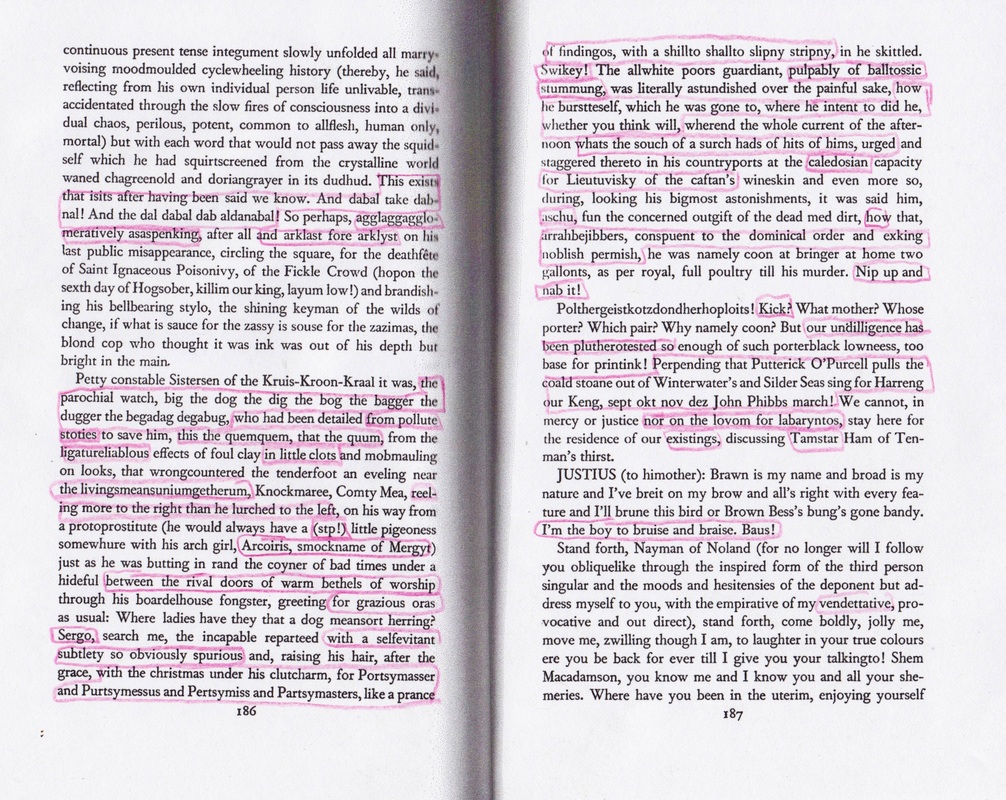

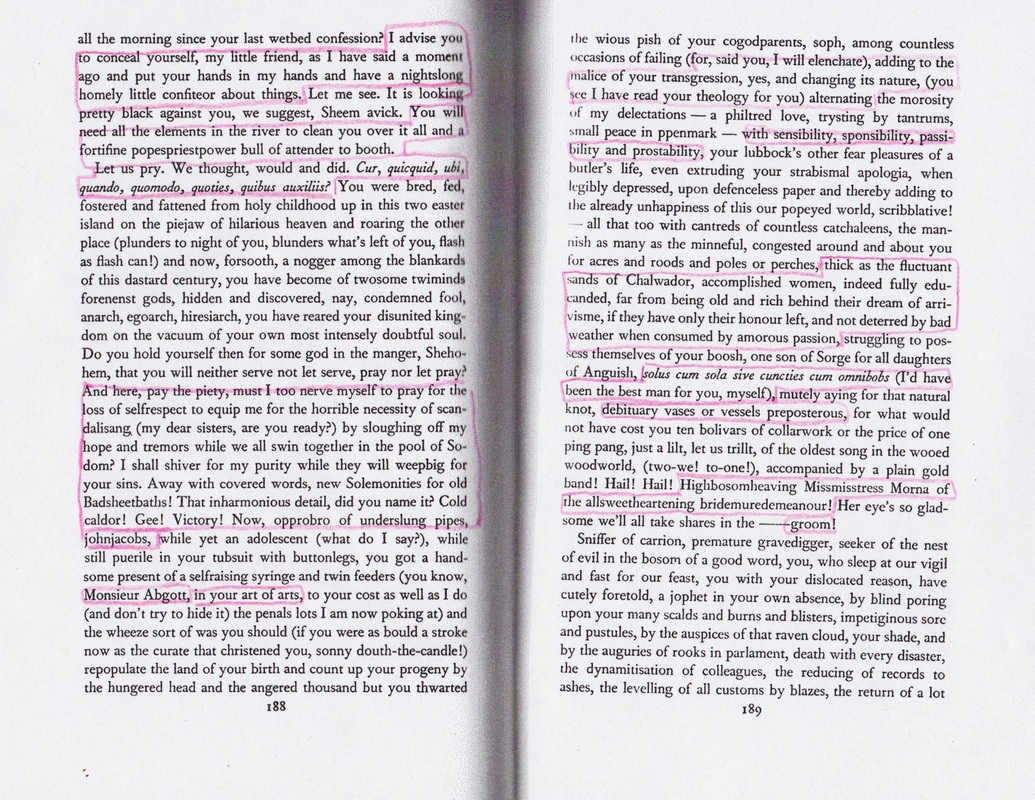

This is far from complete, the marginalia chiefly serve to indicate fields of material incorporated: for more detail, one may turn to McHugh or fweet.org. To get a visual sense of Joyce's "accretive composition" certainly accounts for the

This is far from complete, the marginalia chiefly serve to indicate fields of material incorporated: for more detail, one may turn to McHugh or fweet.org. To get a visual sense of Joyce's "accretive composition" certainly accounts for the

|

elastic syntax of the Wake. A list is particularly prone to expansion, but note the list that was only slightly modified between transition and 1939: the "implausible catalogue" is not the result of a simple desire to fatten the text: it is an element of Joyce's initial conception. I have not noted the differences in paragraphing between the two. Perhaps Joyce had not yet decided on 42 paragraphs for the final version (Joyce was 42 years old when he first started work on Shem) or perhaps the peculiar demands of magazine publication made strict adherence to paragraph form bothersome. "A word from our sponsor" appears to be 2 paragraphs in transition; I suspect a printer's error.

A far more thorough account of the "transitions" of Shem can be found in How Joyce Wrote Finnegans Wake, edited by Luca Crispi and Sam Slote, University of Wisconsin, 2007; "Cain-Ham-(Shem)-Esau-Jim the Penman," Ingeborg Landuyt. |

|